No Crap: Missing 'Mega Poop' Starves Earth

Earth has a problem: not enough poop.

The extinction of megafauna both at land and at sea has led to a shortage of mega manure, new research finds. As a result, the planet's composting and nutrient-recycling system is broken.

"This broken global cycle may weaken ecosystem health, fisheries and agriculture," study researcher Joe Roman, a biologist at the University of Vermont, said in a statement. [8 of the World's Most Endangered Places]

Missing manure

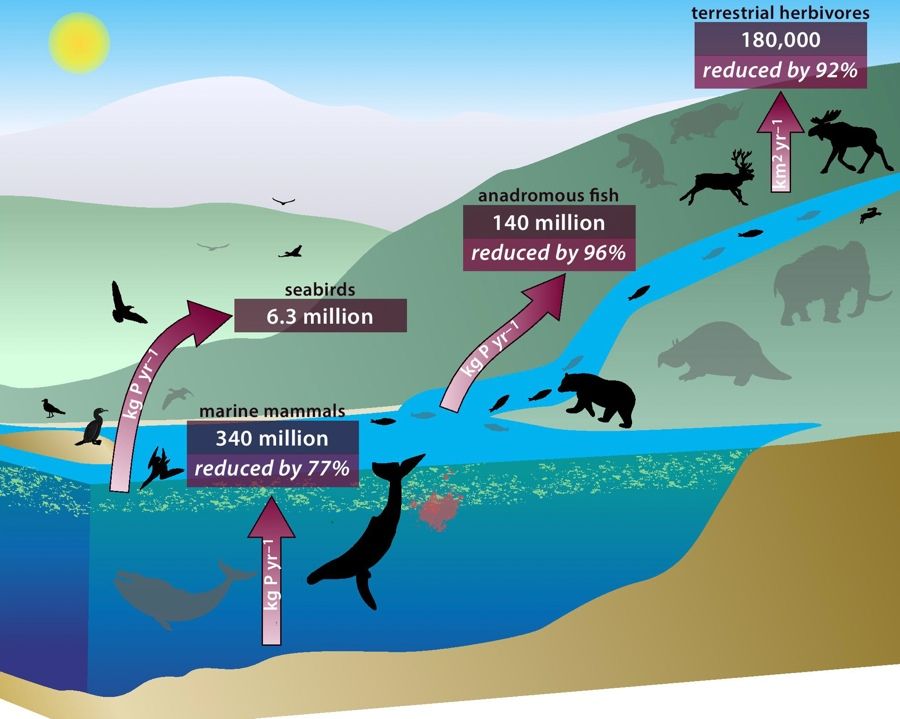

Unappetizing as it may seem, poop is an effective way to spread nutrients around. Now-extinct animals such as mammoths, mastodons and giant sloths were once extremely effective at fertilizing the soil; today, though, those huge land animals are extinct. As a result, natural poop-fertilization by land animals has dropped to 8 percent of what it was at the end of the last ice age, Roman and his colleagues report today (Oct. 26) in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

The situation is even worse in the ocean, where nutrient transport via pooping is estimated at a mere 5 percent of historic values. Humans have hunted large whales down to just 34 percent of the animals' former populations (some estimates put current whale numbers as low as 1 percent of their pre-whaling levels), the researchers wrote.

These deep-diving animals' feces spread the nutrient phosphorous around the ocean, so declines in numbers result in a fall in nutrient transport. In particular, whales feed deep in the ocean, but defecate their nutrient-rich waste in shallower water. This means that those nutrients aren't lost to the ocean sediment. Overall, the researchers found, the ability of whales and other marine mammals to transport phosphorous is down 77 percent from before the days of widespread hunting.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

These numbers are particularly dire in some regions. In the North Atlantic Ocean, for example, the nutrient-transport ability of whales is 14 percent of its historical value, the researchers found. In the North Pacific Ocean, it's 10 percent; in the Southern Ocean, it's a paltry 2 percent.

Likewise, the loss of nutrient transport from land animals is uneven. In Africa, where huge animals like elephants still live, nutrient transport from manure is at 46 percent of what it was about a million years ago. On all other continents, the number is less than 5 percent, with South America at a mere 1 percent of its original capacity.

From sea to land

Poop is also an effective way to move nutrients from sea to land. Seabirds pluck fish from the ocean, then come back to nesting sites and poop copiously (penguin poop stains can even be seen from space). Another form of nutrient transport from sea to land comes in the form of dead fish. Salmon and other species that swim upstream into rivers to spawn and then die are called anadromous fish. Their rotting bodies become part of the terrestrial ecosystem.

But both the collapse of fisheries and the fall in seabird numbers have endangered this sea-to-land pipeline. Phosphorous movement via both bird poop and dead fish is down an estimated 96 percent, Roman and his colleagues found.

The researchers made these estimates using mathematical models based on historical estimates, along with current species populations and ranges from the International Union for Conservation of Nature. However, the scientists could not prove that the missing poop has led to declines in the fertility of the land; the data to determine that simply do not exist, the researchers wrote. However, the findings suggest that a decline in fertility in some regions is likely, the scientists added.

"Previously, animals were not thought to play an important role in nutrient movement," study researchers Christopher Doughty, an ecologist at the University of Oxford in the United Kingdom, said in the statement. However, this misunderstanding may have arisen for a good reason: By the time humans started studying nutrient transport, most of the large, important mammals that played this role were gone.

"This once was a world that had 10 times more whales; 20 times more anadromous fish, like salmon; double the number of seabirds; and 10 times more large herbivores — giant sloths and mastodons and mammoths," Roman said. Domesticated animals, like cattle, are too fenced in and concentrated to play this role, the researchers found.

Conservation measures could be put in place to restore this odiferous transport system, Roman said. Larger bison herds could be re-established on the Great Plains in the United States, for example, and marine protections strengthened for large ocean-goers, he said.

"We can imagine a world with relatively abundant whale populations again," Roman said.

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.