Ancient Tiny Whale Hunted with Pointy Teeth, Oversize Gums

Before baleen whales developed their iconic bristled filter-feeding structures, they relied on their pointy teeth and a suctioning method to nab and gulp down prey, a new study finds.

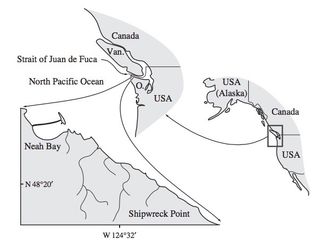

The findings are based on the fossilized remains of a newfound species of early baleen whale. Paleontologists Jim Goedert and Bruce Crowley, both researchers at the Burke Museum at the University of Washington in Seattle, discovered the fossilized whale off the northern tip of Washington's Olympic Peninsula.

At 30 million to 33 million years old, the newly identified species of whale is one of the oldest and smallest known baleen whales to swim around Earth's oceans, said Felix Marx, a postdoctoral fellow at the National Museum of Nature and Science of Japan and the study's lead researcher. [Whale Album: Photos Reveal Giants of the Deep]

The whale measured just over 6.5 feet (2 meters) long, making it much smaller than today's smallest baleen whale, the 21-foot-long (6.4 m) pygmy right whale, and almost 14 times smaller than the 90-foot-long (27.5 m) blue whale, the largest modern baleen whale.

Moreover, the newfound whale skeleton has 17 preserved teeth — a finding that reveals information about how these early whales hunted and fed, Marx said.

He and his colleagues named the new species Fucaia buelli after the Strait of Juan de Fuca, where they found the whale, and Carl Buell, an illustrator known for drawing living and extinct marine animals.

Toothy whales

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Modern baleen whales don't have teeth.

"Instead, they filter small animals directly from the water using a series of comblike baleen plates suspended from their upper jaws," Marx told Live Science in an email.

But the baleen whales' ancestors — including F. buelli — did have teeth, raising the question of how baleen whales lost their teeth without losing the ability to hunt and feed during the transition to baleen-only feeding. Some studies suggest that ancient whales had teeth and then developed baleen before losing their teeth.

"However, Fucaia now shows that the transition was probably more complex," Marx said. "The teeth of Fucaia are so large that they line the entire upper jaw, and thus simply leave no room for baleen. Wear on the teeth also shows that the upper and lower teeth sheared against each other as the mouth opened and closed; thus, any baleen that might have been present would constantly have been caught between the teeth."

Even without baleen plates, F. buelli would have been a successful hunter, Marx said. The researchers suggested that the whale used its teeth and a suctioning technique to capture prey, or at least it caught prey with its teeth, and then sucked it to the back of its mouth to swallow it.

"Suction feeding is common among living marine mammals, and seen in many [living] toothed whales and dolphins, as well as the gray whale," Marx said.

Two key features suggest that F. buelli used this suctioning to filter food from the water, he said. First, the fossils indicate that the whale had large gums, which could have helped the creature seal off the sides of its mouth when its jaws were slightly opened.

"The effect of this would be to reduce the size of the mouth opening, and thus to concentrate the flow created by suction at the tip of the snout," Marx said. [Marine Marvels: Spectacular Photos of Sea Creatures]

Secondly, living whales create suction in their mouths by using strong muscles to pull the tongue and throat backward and downward. Fossil evidence suggests that some of these muscles were well developed in F. buelli, Marx said.

This suctioning technique could have eased the transition from toothy to baleen-only whales, he said.

"As whales evolved better suction, they were able to catch smaller prey than teeth alone could handle but, at the same time, needed a more efficient way to expel the water sucked in with the food," Marx said. "This need is perfectly matched by baleen, which developed from the already enlarged gums and provided an easy way to expel excess water while, at the same time, retaining the prey inside the mouth."

The new study is an exciting "solid paper," said Jorge Velez-Juarbe, a curator of marine mammals at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County who was not involved in the new study.

"The description is fantastic," Velez-Juarbe said. "I think it helps us understand the early evolution of this group of whales."

The study was published online today (Dec. 2) in the journal Royal Society Open Science.

Follow Laura Geggel on Twitter @LauraGeggel. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.