SAN FRANCISCO — The Arctic is warming at an unprecedented rate, new research suggests.

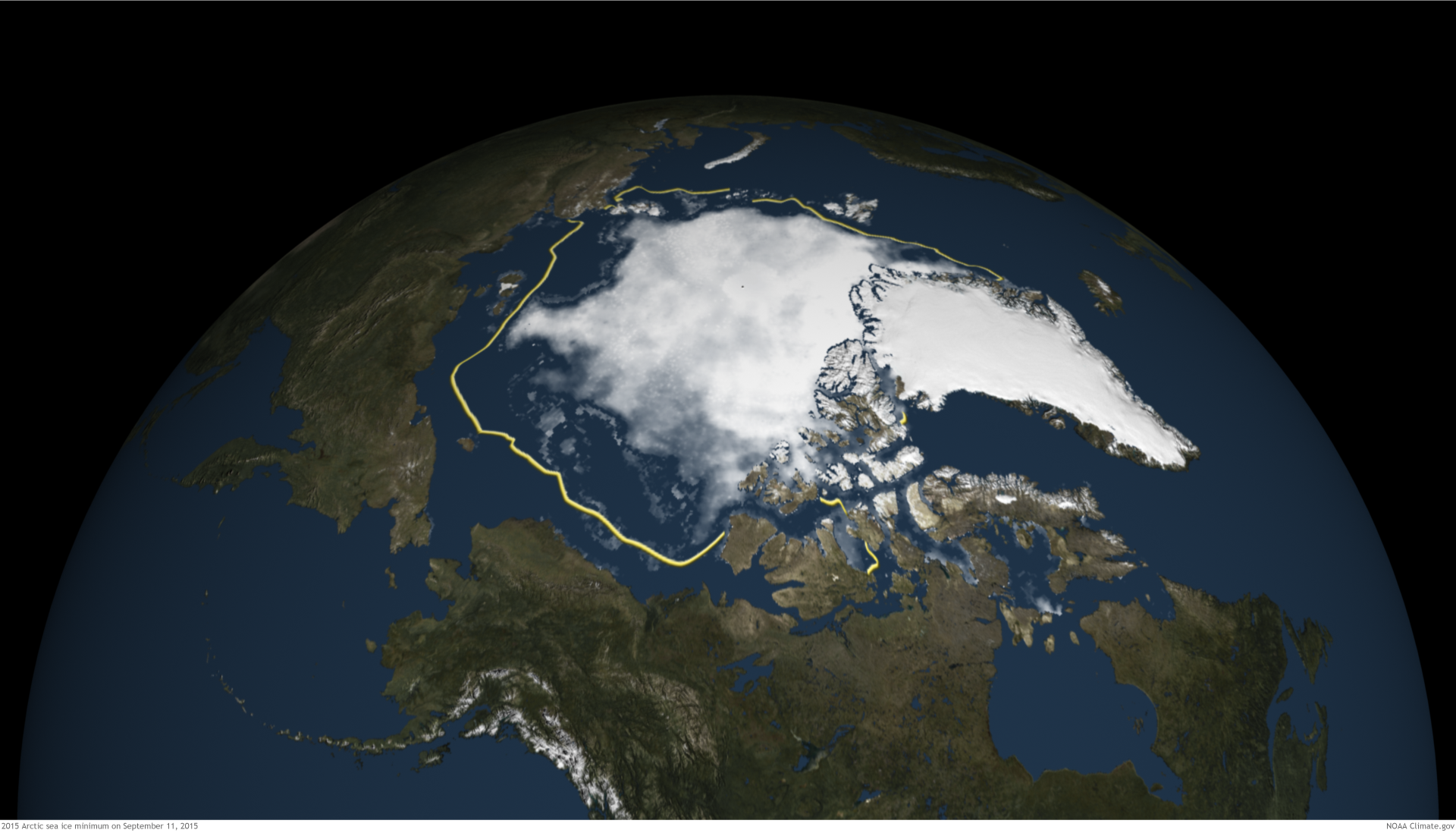

Last year was the warmest on record for the Arctic, and sea ice extent was at an all-time low since record keeping began in 1979. And more than half of the Greenland ice sheet melted in 2015.

"Warming is happening more than twice as fast in the Arctic than anywhere else in the world," said Rick Spinrad, the chief scientific officer a the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), here in a press briefing at the annual meeting of the American Geophysical Union. "We know this is due to climate change."

These changes, along with others tied to a warming planet, have already caused changes in the flora and fauna in the planet's northern climes, researchers said. [Images of Melt: Earth's Vanishing Ice]

Warmer, wetter, weirder

The average air temperature above Arctic land was 2.3 degrees Fahrenheit (1.3 degrees Celsius) warmer between October 2014 and September 2015 compared with the average between 1981 and 2010. That represents a 5.4-degree-F (3 degrees C) increase from the average air temperatures in 1900.

In addition, the sea ice extent during those months was the lowest since 1979, when record keeping began. On the day when ice reached its maximum in 2015, 70 percent had formed in the previous year, with only 3 percent of the ice considered old, meaning it had been around for more than four years, said Kit Kovacs, a senior scientist at the Norwegian Polar Institute.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

By contrast, in the 1980s, about 20 percent of the sea ice was old and about 45 percent had formed that year. This suggests more and more of the sea ice is melting every year.

The Greenland ice sheet continues its dramatic melting. More than 50 percent of the ice sheet melted this year. In addition, the Arctic rivers are swollen with more water than they have been in the past, with the eight biggest rivers releasing 10 percent more water than in the years 1980 to 1989, likely because of greater precipitation due to global warming, said Martin Jeffries, the program officer and science adviser for the U.S. Office of Naval Research.

Wildlife and plant life

Already, the effects of a warming climate are showing up on land. Walruses typically mate, give birth and rear their young on the sea ice because it allows them easy access to food and shelter from storms. However, in Alaska, many of the female and baby walruses are now hauling out as far as 110 miles (180 kilometers) onto land, Kovacs said.

The tundra is also browning, with less vegetation on land. While one year of browning isn't cause for concern, "we're looking at, depending on where in the Arctic, a two- to four-year consistent drop in vegetation. It's something that's actually just gotten on our radar from a terrestrial ecology perspective," said Howard Epstein, an environmental scientist at the University of Virginia.

It's not clear exactly why the tundra is changing; everything from aerosols in the air to snow cover, cloudiness and other conditions can affect vegetation, Epstein said.

However, "if you increase vegetation on the landscape, it tends to have a protective effect on the permafrost," Epstein said. That's because the vegetation itself, as well as the windblown snow that it traps, insulates the ground below, increasing winter ground temperatures and decreasing summer soil temperatures, he said. On the other hand the tops of shrubby plants may poke out from the snow during the spring, decreasing the reflectivity of the surface and leading to greater heat absorption, Epstein said.

For instance, in the Barents Sea, cold-water Arctic fishes have seen their habitat shrink, as warmer-water predators such as cod, beaked redfish and the flatfish called long rough dab have invaded the colder reaches of the sea, Kovacs said.

Follow Tia Ghose on Twitter and Google+. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Tia is the managing editor and was previously a senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.