Archaeologists Return to Neanderthal Cave as ISIS Pushed from Iraq

As the terrorist group ISIS is pushed out of northern Iraq, archaeologists are resuming work in the region, making new discoveries and figuring out how to conserve archaeological sites and reclaim looted antiquities.

Several discoveries, including new Neanderthal skeletal remains, have been made at Shanidar Cave, a site in Iraqi Kurdistan that was inhabited by Neanderthals more than 40,000 years ago.

Additionally, though ISIS did destroy and loot a great number of sites, there are several ways for archaeologists, scientific institutions, governments and law enforcement agencies in North America and Europe to help save the region's heritage, said Dlshad Marf Zamua, a Kurdish archaeologist and doctoral student at Leiden University in the Netherlands. [Photos: Restoring Life to Iraq's Ruined Artifacts]

He criticized antiquity dealers who are benefiting financially from ISIS' looting and destruction, calling on authorities in North America and Europe to prevent those dealers from selling northern Iraq's heritage. "It was said that war was created for selling weapons, but in the situation of our area, the war was created for selling weapons, oil and antiquity objects," Marf Zamua said.

New research

Before ISIS moved into Iraq in the summer of 2014, scientists with 45 foreign missions from 16 countries were conducting archaeological excavations and surveys in the Kurdistan region of northern Iraq, said Marf Zamua.

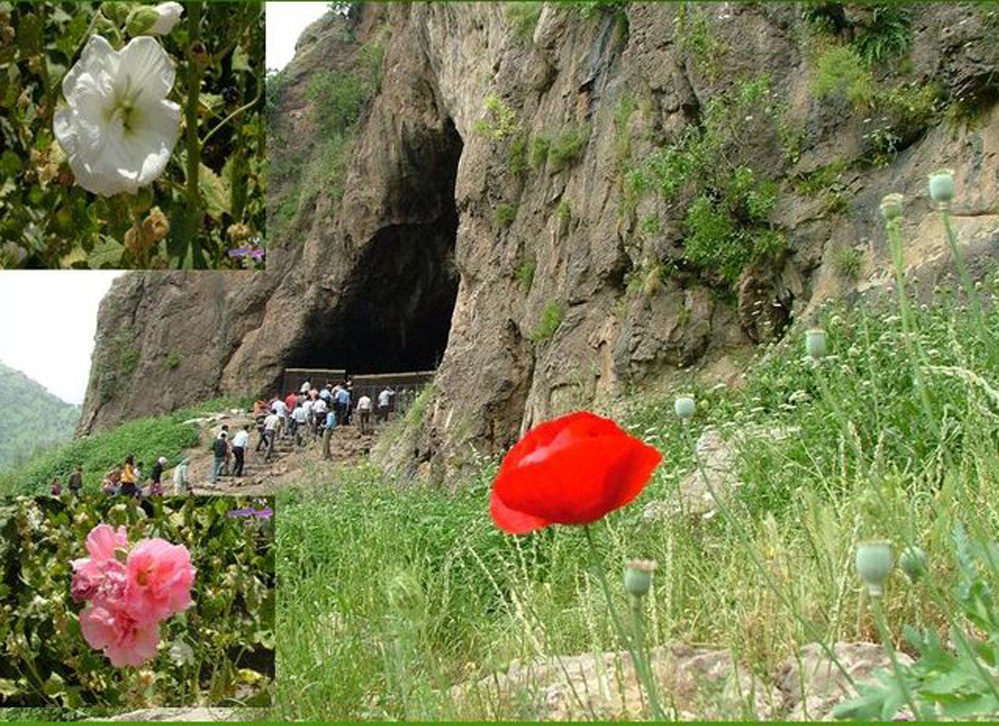

Over the past few months, Kurdish forces have gone on the offensive and, with support from allied air strikes, are pushing ISIS out of the region. And archaeologists are returning to the area, including at Shanidar Cave. This cave was originally excavated between 1952 and 1960 by a team led by archaeologist Ralph Solecki from the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C. The archaeologists at that time found several Neanderthal skeletons and pollen remains suggesting that the Neanderthals placed flowers in graves before burial.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

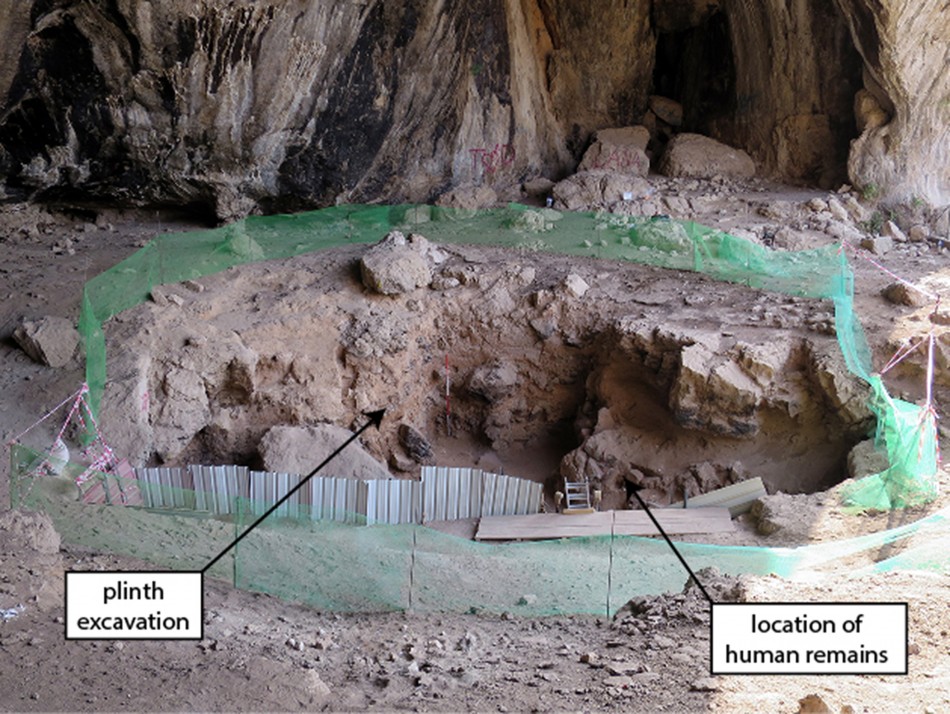

In an article recently published in the journal Antiquity, a team that has recently returned to Shanidar Cave reported finding additional Neanderthal bones, "including a hamate [a wrist bone], the distal ends of the right tibia and fibula, and some articulated ankle bones, scattered fragments of two vertebrae, a rib and long bone fragments."

The newfound bones are likely from one of the Neanderthals that archaeologists dug up in the 1950s, said University of Cambridge archaeologist Graeme Barker, who is part of the research team. He said that as excavations continue, new Neanderthal skeletons may be found.

Additionally the team's research is shedding light on the environment in the cave where the Neanderthals lived.

For instance, scientists reporting in another paper published in the journal Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology found that bees were transporting pollen into the cave. This complicates the idea that Neanderthals in the cave buried their dead with flowers, suggesting instead that pollen remains from flowers could have entered the cave through natural means.

Protecting heritage

When ISIS took over parts of northern Iraq, the group began looting and destroying archaeological sites such as ancient Assyrian cities like Nimrud. After bulldozing these cities, but before blasting them, ISIS looted thousands of artifacts from the sites, Marf Zamua said. "Thousands of objects reached the black markets over the world."

Additionally, many unexcavated "Tell" (mound) sites were also bulldozed, looted and blasted. Those sites contained artifacts that have not yet been excavated. There "are hidden treasure [within these mounds], and by losing any of them, we lose an important part of history and civilization of Mesopotamia," Marf Zamua said.

In addition to curtailing the black market, scientific organizations in the West can help train Iraqi, Kurdish and Syrian archaeologists in conservation techniques, Marf Zamua said. "Institutes can offer local archaeologists scholarships in restoration, protecting heritage and museum studies," he said.

Additionally, in Erbil (the capital of Iraqi Kurdistan), the Iraqi Institute for the conservation of Antiquities and Heritage offers "courses taught by specialists in conservation of all types of objects, materials and architecture," said Marf Zamua. Volunteer guest lecturers from universities and museums in the West help teach the courses.

Those with professional expertise who are willing to travel to Erbil could contact the institute and offer to volunteer, Marf Zamua said, noting that the institute provides accommodations and food free of charge.

Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Owen Jarus is a regular contributor to Live Science who writes about archaeology and humans' past. He has also written for The Independent (UK), The Canadian Press (CP) and The Associated Press (AP), among others. Owen has a bachelor of arts degree from the University of Toronto and a journalism degree from Ryerson University.