Big-Eared Statues Reveal Ancient Egyptian Power Couple

Six ancient statues of Egyptians, some with round faces and big ears, have been found near the Nile River in Upper Egypt.

The statues, which were once sloughed off their original bluff in an earthquake and buried in Nile silt, are of a man named Neferkhewe and his family. Neferkhewe bore the titles of chief of the Medjay (northern Sudan) and overseer of the foreign lands some 3,500 years ago, during the reign of Pharaoh Thutmose III. The statues, and the carved alcove in which they reside, had been open to the elements for at least 1,500 years before being buried, but the carvings are in incredible condition, said John Ward, the assistant director of the Gebel el Silsila Survey Project that uncovered the statues.

"To be there when their faces look back at you after 2,000 years of being covered with silt is an experience that can't be put into words," Ward told Live Science "It's just a pure honor." [See Photos of the Ancient Egyptian Statues of Neferkhewe]

Ancient ritual

The newly discovered statues sit inside two cenotaphs, or "false tombs." Thirty-two cenotaphs line the Nile River at the Gebel el Silsila site, which is also where many of the sandstone blocks used to build Egypt's temples were quarried over the centuries.

Such quarrying would have been rough, industrial work, and the Gebel el Silsila cenotaphs are a somewhat mysterious example of elegance and beauty in this environment. These carved alcoves were a bit like memorials for certain elite families, Ward said. No one was buried in them, but family members or well-wishers could come to leave offerings to the dead, to perform rituals and perhaps to grieve.

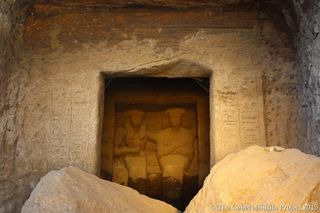

"We don't know why these 32 families chose Silsila to place their cenotaphs here," Ward said. The two newly discovered cenotaphs contain the most well-preserved statues ever found at the site, he said. In one, the cenotaph owner and his wife sit side by side on a chair, the man wearing a shoulder-length wig and posing with his arms crossed over his chest — a pose known as the "Osirian" position after Osiris, the Egyptian god of the afterlife. The man's wife has one arm on her husband's back and the other on her own abdomen. [Image Gallery: Amazing Egyptian Discoveries]

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The second cenotaph holds four statues and carvings identifying the patriarch as Neferkhewe. He is flanked by his wife Ruiuresti and two children, but the couple must have had more kids, Ward said, because other children are depicted in carvings bringing offerings to their parents.

Personal history

For Neferkhewe and his family, the re-discovery of their names would have been an event of great religious significance.

"To preserve one's name, it's pivotal to the religion," Ward said. "Without a name you wouldn't have an identity in the afterlife, so you wouldn't exist."

Speaking Neferkhewe's name out loud for the first time in at least 2,000 years "gives him the immortality that he dreamed of," Ward said.

"We bring them to life again," said Maria Nilsson, the survey project's mission director.

The discovery helps personalize Silsila in other ways. The statues hint at what the family may have looked like, with their round-cheeked faces and large ears. With further work, it may be possible to find the actual tombs of the family or their relatives in Luxor or Thebes, Ward said.

"It's like a window into their life," he said.

Ritual was important at Silsila, which also boasts a stunning rock-cut temple called a "speos," constructed with solar and lunar alignment in mind, Ward said. An annual Nile festival once celebrated at the site would have involved thrusting the book of the Nile god Hapi into the river to bring the nutrient-rich floodwaters to Egypt. While excavating mummies and pyramids is "very exciting," Ward said, day-to-day life is closer to the surface at Silsila.

The researchers said they plan to continue cleaning and translating the reliefs carved into the two new cenotaphs. They said they're hoping to learn the names of Neferkhewe's other children. The excavations are funded in part by the nonprofit Friends of Silsila.

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Most Popular