Prosthetic Leg with Hoofed Foot Discovered in Ancient Chinese Tomb

The 2,200-year-old remains of a man with a deformed knee attached to a prosthetic leg tipped with a horse hoof have been discovered in a tomb in an ancient cemetery near Turpan, China.

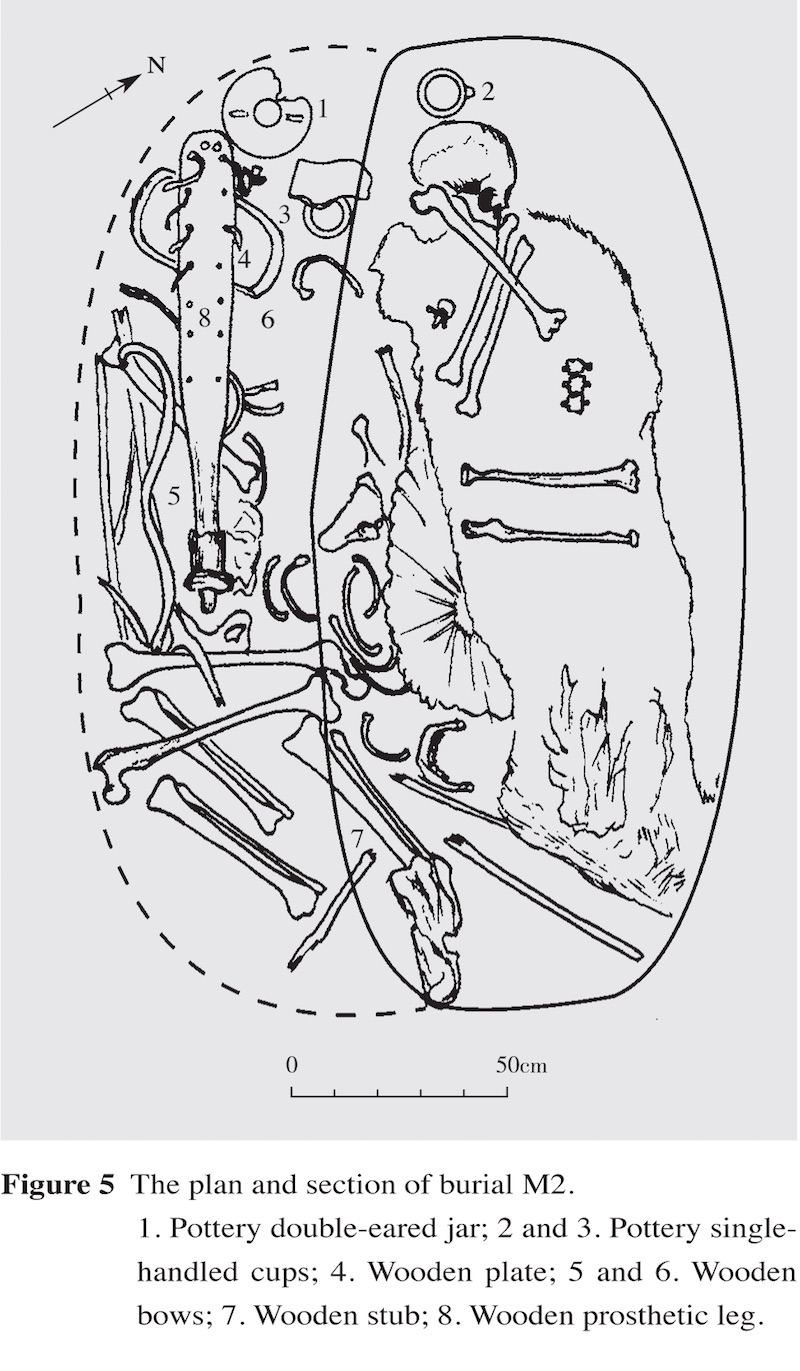

The tomb holds the man and a younger woman, who may or may not have known the male occupant, scientists say.

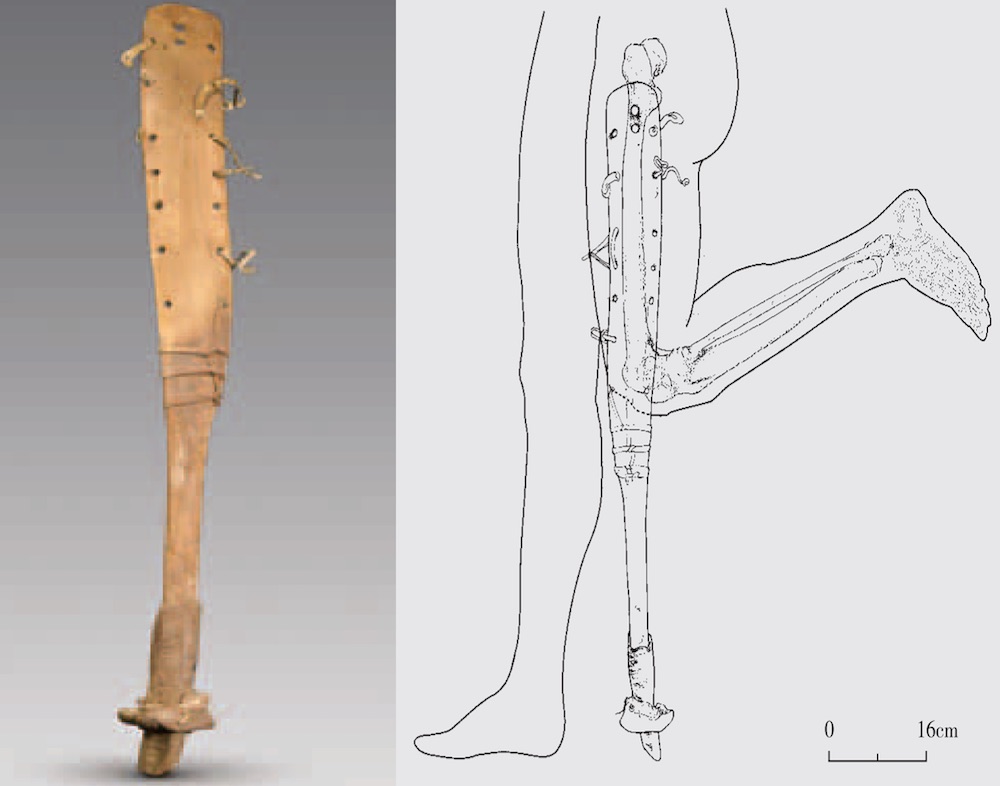

"The excavators soon came to find that the left leg of the male occupant is deformed, with the patella, femur and tibia [fused] together and fixed at 80 [degrees]," archaeologists wrote in a paper published recently in the journal Chinese Archaeology. [In Photos: Ancient King's Mausoleum Discovered in China]

The fused knee would have made it hard for the man to walk or ride horses without the prosthetic leg, the researchers found. The man couldn't straighten his left leg out so the prosthetic leg, when attached, allowed the left leg to touch the floor when walking. The horse hoof at the bottom of the prosthetic leg acted like a foot.

The prosthetic leg was "made of poplar wood; it has seven holes along the two sides with leather tapes for attaching it to the deformed leg," the archaeologists wrote. "The lower part of the prosthetic leg is rendered into a cylindrical shape, wrapped with a scrapped ox horn and tipped with a horsehoof, which is meant to augment its adhesion and abrasion."

"The severe wear of the top implies that it has been in use for a long time," they added.

Radiocarbon dating indicates that the tomb in Turpan (also spelled Turfan) dates back around 2,200 years. The only other known prosthetic leg in the world that dates to that time is part of a bronze leg found in Capua, Italy. That leg was destroyed in a bombing raid during World War II. Prosthetic toes, dating to earlier times, have been found in Egypt.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Who used it?

Two other studies, published in the journals Bridging Eurasia and Quaternary International, provide more details about the man who used the hoofed leg. Researchers estimate that the man was about 5 feet 7 inches (1.7 meters) tall, and between 50 and 65 years old when he died.

What caused the odd fusion of his left knee joint? "Different causes, like inflammation in or around the joint, rheumatism or trauma, might have resulted in this pathological change," archaeologists wrote in the journal Bridging Eurasia.

Researchers found evidence that the man was infected with tuberculosis at some point in his life. They think that inflammation from the infection may have resulted in a bony growth that allowed his knee to fuse together. "The smooth surface of the bones affected by the ankyloses [joint fusion] suggests the active inflammatory process stopped years before death," the researchers wrote in Bridging Eurasia.

The man appears to have been a person of modest means, as he was buried with nonluxurious items: ceramic cups and a jar, a wooden plate and wooden bows, the archaeologists found. Sometime after he died, his tomb was reopened, and the body of a 20-year-old woman was put in, disturbing the man's bones. What relationship the man and woman had (if any) is unknown. The tomb was one of 30 that archaeologists excavated in the cemetery.

Gushi people

Based on the results of the radiocarbon dating, "the occupants of the cemetery might have belonged to the Gushi [also spelled Jushi] population," archaeologists wrote in the Chinese Archaeology article.

Little is known about these people. Ancient Chinese texts suggest that the Gushi had a small state. "As recorded in the Xiyu zhuan (the Account of the Western Regions) of the Hanshu (Book of Han, by Ban Gu), during the middle of the Western Han, there lived in the Turfan Basin the Gushi population, who constitutes one of the 'Thirty-six States of the Western Regions' of the Qin and Han Dynasties," the archaeologists wrote.

The Gushi state was conquered by China's Han Dynasty during a military campaign in the first century B.C., according to ancient records. "Given that the study of the Gushi culture is yet at its nascent stage, the [cemetery] provides valuable new materials," the archaeologists wrote.

Excavations at the cemetery were conducted between 2007 and 2008 by scientists at the Academia Turfanica, a research institute. A paper reporting their findings was published in 2013, in Chinese, in the journal Kaogu. That paper was recently translated and published in the journal Chinese Archaeology.

The papers reporting the study of the man's skeleton were published in 2014 in the journal Bridging Eurasia and in 2013 in the journal Quaternary International.

Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Owen Jarus is a regular contributor to Live Science who writes about archaeology and humans' past. He has also written for The Independent (UK), The Canadian Press (CP) and The Associated Press (AP), among others. Owen has a bachelor of arts degree from the University of Toronto and a journalism degree from Ryerson University.