Sexy Signal? Frill and Horns May Have Helped Dinosaur Communicate

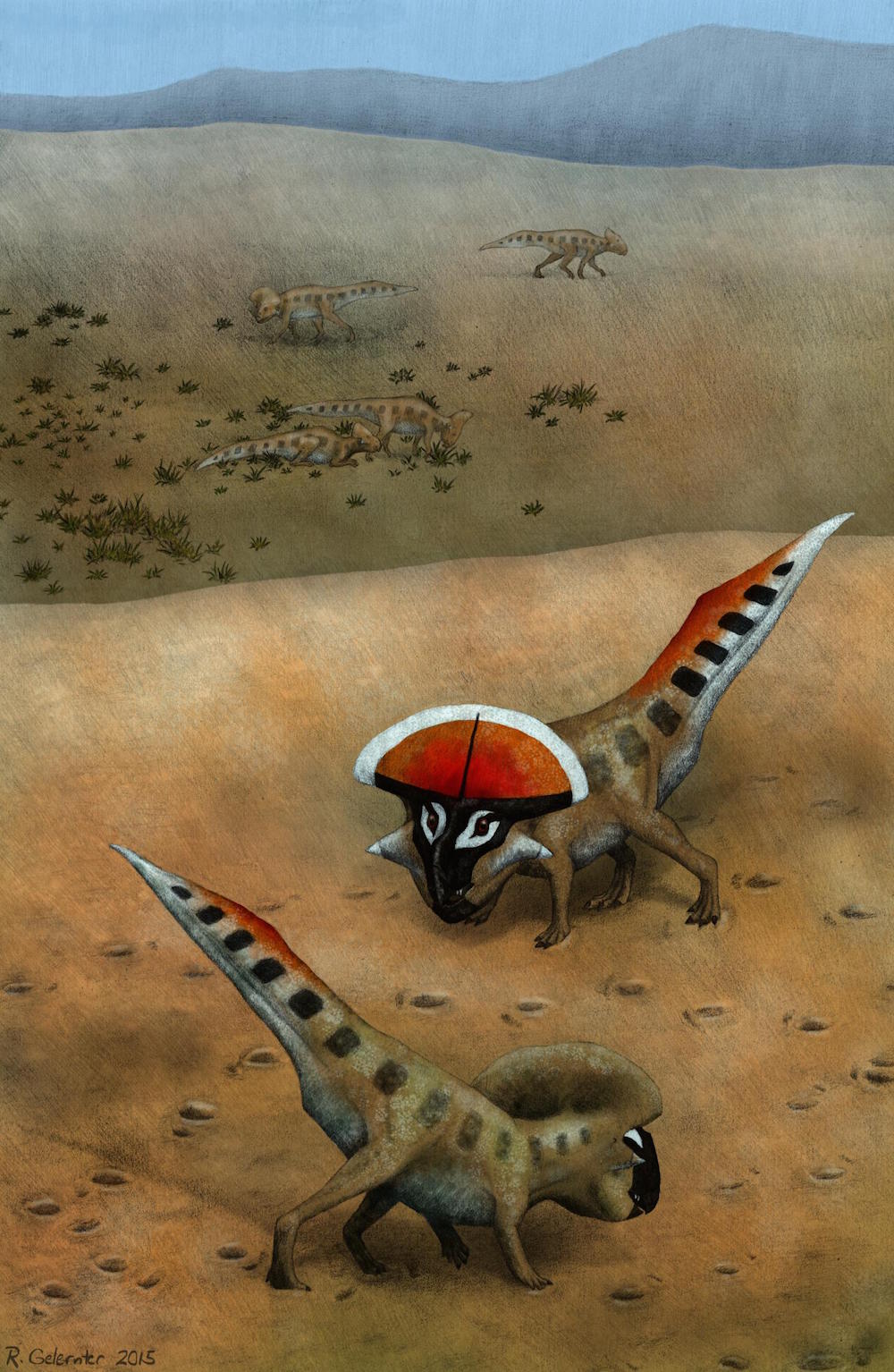

The fancy frill and cheek horns that adorned the head of a triceratops relative may have helped the dinosaur communicate, possibly acting as a social or sexy signal, a new study suggests.

This isn't the first time researchers have analyzed the skull of Protoceratops andrewsi, a sheep-size dinosaur with four legs that dates to the Cretaceous period, about 75 million years ago. Protoceratops andrewsi lived just before Triceratops, and paleontologists regularly come across their fossilized remains in Mongolia.

As researchers collected more specimens over the years, they noticed a peculiar pattern: The frill was absent in juveniles, but it quickly grew disproportionately larger in relation to the dinosaur's size in adulthood. [Tiny & Old: Images of 'Triceratops' Ancestors]

This sudden burst in frill growth suggests that 6.5-foot-long (2 meters) P. andrewsi used the structure as a signal, possible to convey its dominance and age, and maybe even serve as a sexual sign, the researchers said.

"Paleontologistshave long suspected that many of the strange features we see in dinosaurs were linked to sexual display and social dominance, but this is very hard to show," study lead author David Hone, a lecturer of zoology at Queen Mary University of London (QMUL), said in a statement. "The growth pattern we see in Protoceratops matches that seen for signaling structures in numerous different living species and forms a coherent pattern from very young animals right through to large adults."

To investigate, the researchers measured how the frill changed in length and width in 37 dinosaurs over four life stages, including hatchling babies, young animals, near-adults and adults. The frill changed in size, as well as shape, becoming proportionally wider as the dinosaur grew up, they noted.

The dinosaur's cheek horns also grew larger with age, but they did not grow as much as the frills, according to the study. This finding suggests that P. andrewsi used its cheek horns for signaling as well, but more evidence is needed to confirm that idea.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"Biologists are increasingly realizing that sexual selection is a massively important force in shaping biodiversity both now and in the past," said study co-author Rob Knell, a professor of evolutionary ecology at QMUL.

"Not only does sexual selection account for most of the stranger, prettier and more impressive features that we see in the animal kingdom, [but] it also seems to play a part in determining how new species arise," Knell said. "And there is increasing evidence that it also has effects on extinction rates and on the ways by which animals are able to adapt to changing environments."

The study raises some interesting and compelling interpretations of P. andrewsi's frills and cheek horns, said Andrew Farke, a paleontologist at the Raymond M. Alf Museum of Paleontology in Claremont, California, who was not involved in the new research.

"I would suspect that there is some sort of role in reproduction for this, if it's the adults that are showing the biggest size of this, it makes sense," Farke told Live Science. "On the other hand, it's also likely that it could just be for how old are you relative to the next animal, so who gets to the food first?"

The study was published online Jan. 13 in the journal Palaeontologia Electronica.

Follow Laura Geggel on Twitter @LauraGeggel. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.