Physics of Skipping Stones Could Make Bounceable Naval Weapons

Skipping elastic balls off water is much easier to do than trying to make stones "hop" across the surface of a lake, but a new study of water-impact physics isn't all fun and games — the research could improve everything from aquatic toys to naval weapons and inflatable rafts, scientists said.

Studying how objects ricochet across water has a wide range of applications. For example, during the Age of Sail, when sailing ships ruled the seas for trade and warfare, cannonballs were skipped over the water to bounce onto decks, killing enemy sailors and breaking masts.

"A text titled 'The Art of Shooting [in] Great Ordnaunce' by William Bourne was likely published in 1578, and is the first known account to mention that if cannonballs are fired at a sufficiently low angle they will ricochet across the water surface," said study co-author Tadd Truscott, a fluid dynamicist at Utah State University in Logan. [The Mysterious Physics of 7 Everyday Things]

Furthermore, during World War II, British engineer Barnes Wallis developed a bomb that could bounce across water, which the Royal Air Force used against Germany in 1943. "This bomb was made to spin at a great rate before impact, enabling it to move along the water surface and avoid torpedo nets on its way to destroy key German dams," Truscott told Live Science.

In addition, studying how the basilisk lizard can run across the water — a capability that earned these reptiles the moniker "Jesus lizard" — could one day help researchers build robots that can do the same. "Water impact has been heavily studied for the past 100 years, with motivations ranging from understanding the physics of seaplane landing to, more commonly, a simple desire to better understand the world in which we live," Truscott said.

A stone can be coaxed to ricochet multiple times across the surface of water, provided it is the right, disk-like shape and is flicked with the right speed and trajectory. However, research suggests that elastic spheres are much easier to skip, even with only mediocre launches.

A toy known as the Water Bouncing Ball, or Waboba, inspired Truscott's latest research into the physics of skipping spheres. The tennis- ball-size Waboba can't bounce on land but is able to skip across water with relative ease.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"Our approach was playful at first," Truscott said in a statement. "My son and nephew wanted to see the impact of the elastic spheres in slow motion, so that was also part of the initial motivation. We simply wondered why these toys skip so well. In general, I have always found that childish curiosity often leads to profound discovery."

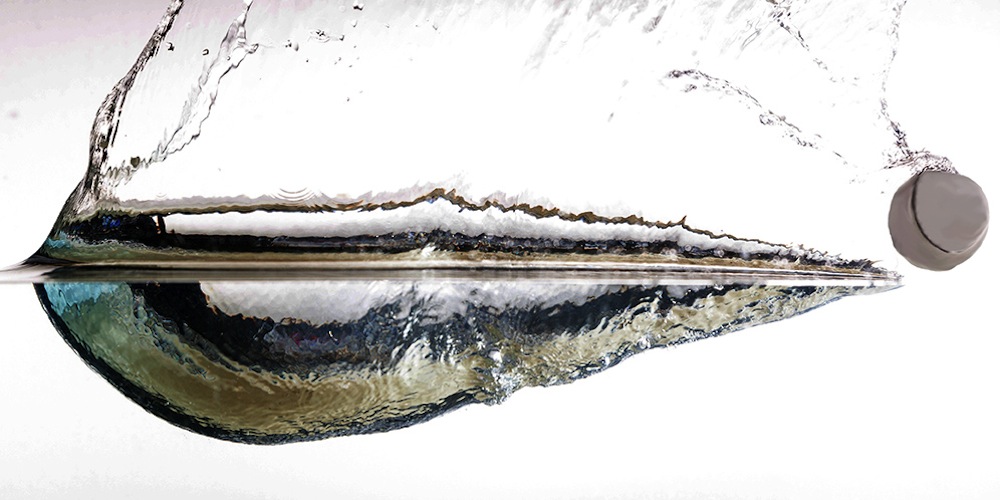

To learn more about how elastic objects skip, Truscott and his colleagues used high-speed cameras to capture images of elastic balls bouncing across tanks of water in a lab. The scientists discovered that elastic spheres can demonstrate superior ricocheting ability for a variety of reasons.

First, the act of elastic balls hitting water can deform them into disklike shapes resembling the kind of stones one might find on a shore. These shapes are ideal for multiple bounces off water; the liquid can exert more force on a flat saucer than a round ball.

In addition, elastic balls can deform into ideal disk shapes regardless of the angles at which they hit the water. This means they can hit the water at a greater range of angles than can rigid disks and still skip, Truscott said.

"I would estimate that a talented amateur stone-skipper might be able to achieve nearly 20 skips with a stone — the world record is 88, but it's very difficult. This would involve years of practice, and [an] ideal stone, calm water and a lucky throw," Truscott said. In contrast, "you could skip an elastic sphere 20 times in a matter of 10 minutes [of practice]."

All in all, the researchers found that elastic spheres can skip when hitting water at angles nearly three times greater than those predicted for rigid spheres. An elastic ball "would also skip at a much slower throwing speed than its rigid friend, if they were thrown at the same angle to the water surface," Truscott said.

"It is still surprising to me when I throw one of these elastic balls at a lake or swimming pool and watch it effortlessly skip several times," Truscott said. "To achieve the same feat with a stone takes considerable skill and velocity, while elastic balls can be skipped by my 5-year-old daughter."

The researchers suggest their work could help improve "inflatable surface craft or skipping projectiles," Truscott said.

The scientists detailed their findings online Feb. 4 in the journal Nature Communications.

Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.