Some of Europe's earliest inhabitants mysteriously vanished toward the end of the last ice age and were largely replaced by others, a new genetic analysis finds.

The finds come from an analysis of dozens of ancient fossil remains collected across Europe.

The genetic turnover was likely the result of a rapidly changing climate, which the earlier inhabitants of Europe couldn't adapt to quickly enough, said the study's co-author, Cosimo Posth, an archaeogenetics doctoral candidate at the University of Tübingen in Germany. [Top 10 Mysteries of the First Humans]

The temperature change around that time was "enormous compared to the climactic changes that are happening in our century," Posth told Live Science. "You have to imagine that also the environment changed pretty drastically."

A twisted family tree

Europe has a long and tangled genetic legacy. Genetic studies have revealed that the first modern humans who poured out of Africa, somewhere between 40,000 and 70,000 years ago, soon got busy mating with local Neanderthals. At the beginning of the agricultural revolution, between 10,000 and 12,000 years ago, farmers from the Middle East swept across Europe, gradually replacing the native hunter-gatherers. Around 5,000 years ago, nomadic horsemen called the Yamnaya emerged from the steppes of Ukraine and intermingled with the native population. In addition, another lost group of ancient Europeans mysteriously vanished about 4,500 years ago, a 2013 study in the journal Nature Communications found.

But relatively little was known about human occupation of Europe between the first out-of-Africa event and the end of the last ice age, around 11,000 years ago. During some of that time, the vast Weichselian Ice Sheet covered much of northern Europe, while glaciers in the Pyrenees and the Alps blocked east-west passage across the continent.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Lost lineages

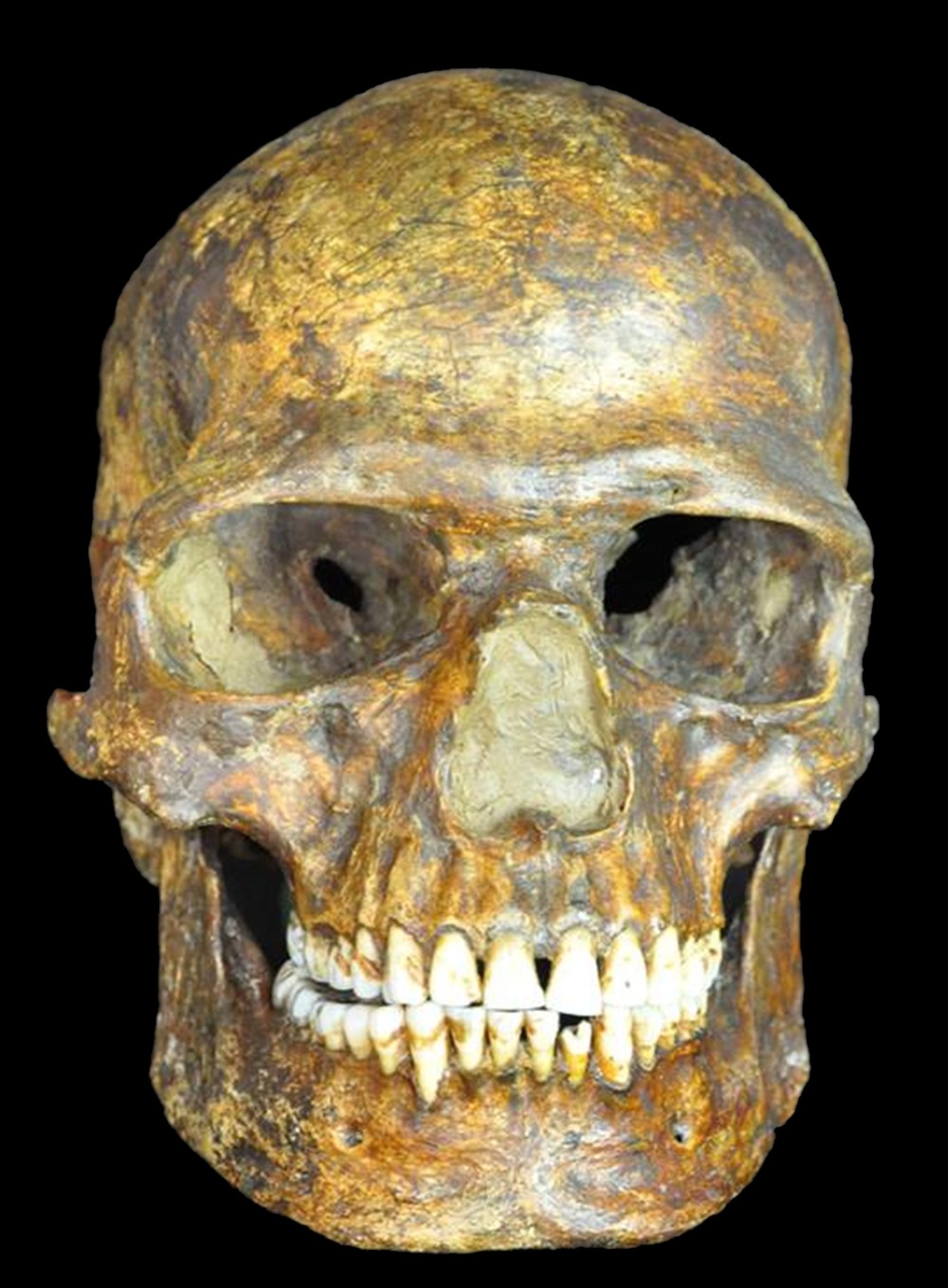

To get a better picture of Europe's genetic legacy during this cold snap, Posth and his colleagues analyzed mitochondrial DNA — genetic material passed on from mother to daughter — from the remains of 55 different human fossils between 35,000 and 7,000 years old, coming from across the continent, from Spain to Russia. Based on mutations, or changes in this mitochondrial DNA, geneticists have identified large genetic populations, or super-haplogroups, that share distant common ancestors.

"Basically all modern humans outside of Africa, from Europe to the tip of South America, they belong to these two super-haplogroups that are M or N," Posth said. Nowadays, everyone of European descent has the N mitochondrial haplotype, while the M subtype is common throughout Asia and Australasia.

The team found that in ancient people, the M haplogroup predominated until about 14,500 years ago, when it mysteriously and suddenly vanished. The M haplotype carried by the ancient Europeans, which no longer exists in Europe today, shared a common ancestor with modern-day M-haplotype carriers around 50,000 years ago.

The genetic analysis also revealed that Europeans, Asians and Australasians may descend from a group of humans who emerged from Africa and rapidly dispersed throughout the continent no earlier than 55,000 years ago, the researchers reported Feb. 4 in the journal Current Biology.

Time of upheaval

The team suspects this upheaval may have been caused by wild climate swings.

At the peak of the ice age, around 19,000 to 22,000 years ago, people hunkered down in climactic "refugia," or ice-free regions of Europe, such as modern-day Spain, the Balkans and southern Italy, Posth said. While holdouts survived in a few places farther north, their populations shrank dramatically.

Then around 14,500 years ago, the temperature spiked significantly, the tundra gave way to forest and many iconic beasts, such as woolly mammoths and saber-toothed tigers, disappeared from Eurasia, he said.

For whatever reason, the already small populations belonging to the M haplogroup were not able to survive these changes in their habitat, and a new population, carrying the N subtype, replaced the M-group ice-age holdout, the researchers speculate.

Exactly where these replacements came from is still a mystery. But one possibility is that the newer generation of Europeans hailed from southern European refugia that were connected to the rest of Europe once the ice receded, Posth speculated. Emigrants from southern Europe would also have been better adapted to the warming conditions in central Europe, he added.

Follow Tia Ghose on Twitterand Google+. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Tia is the managing editor and was previously a senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.