Miami, Houston and Orlando, Florida, are the cities within the continental U.S. that have some of the highest risk of having "local transmission" of the Zika virus, meaning the virus will spread to people from mosquitoes in the local area, new research suggests.

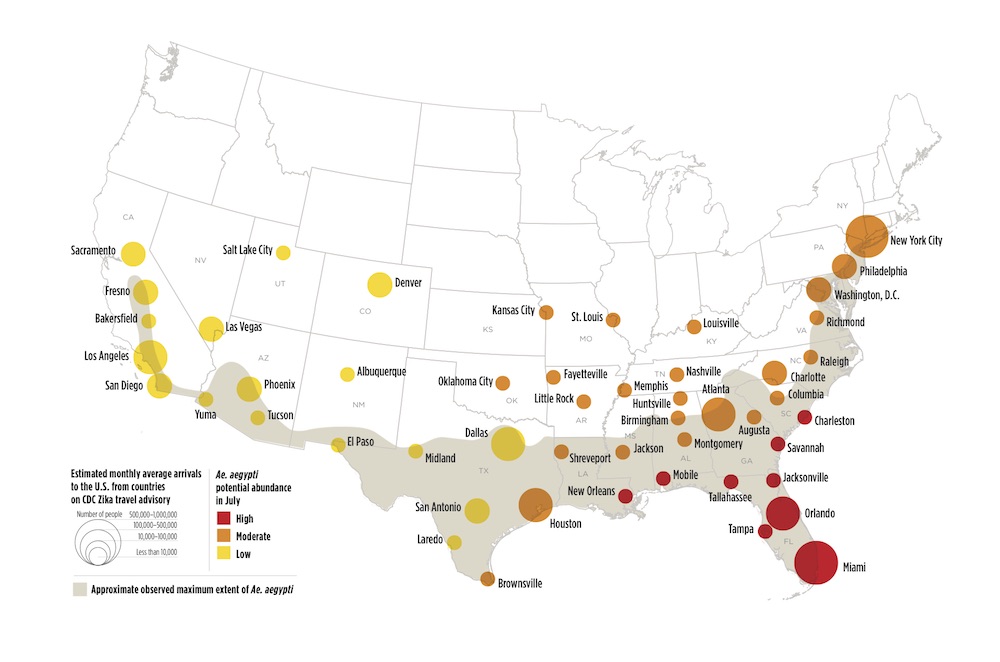

The new analysis combines a host of data on climate, mosquito breeding patterns, poverty and air travel to identify the cities at greatest risk. Overall, the southeast part of the country faces the highest risk, the Eastern Seaboard faces a moderate risk and the western U.S. has a lower risk.

However, evidence from similar viruses suggests that if Zika does begin spreading locally, the spread even in the highest-risk cities will be limited, affecting dozens of people at most, said study co-author Andrew Monaghan, a climate scientist at the National Center for Atmospheric Research in Boulder, Colorado. [Tiny & Nasty: Images of Things That Make Us Sick]

The overall risk to most people in the U.S. is very low, Monaghan said.

"I don't want this to be an alarmist message," Monaghan told Live Science.

Zika virus spread

The Zika virus is spread by the bite of infected mosquitoes from the Aedes genus, including Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus. Only about 20 percent of people who become infected with Zika virus exhibit symptoms, and those who do typically have only mild symptoms, such as fever, red eyes, rash and joint pain. However, Zika infections in pregnant women have been tied to microcephaly in their infants — a condition that causes unusually small brains and heads, and brings lifelong cognitive impairments.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The virus also may be responsible for a rare form of temporary paralysis called Guillain-Barre syndrome that can strike people of any age.

Zika is spreading in more than a dozen countries in the Americas, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and it is possible that the virus will spread within the U.S. because the mosquitoes that transmit the virus live in the country.

These mosquitoes also transmit other viruses, included the ones that cause dengue fever and chikungunya. "The mosquito has been in the U.S. for hundreds of years," Monaghan said. "In 1780, there was a dengue outbreak in Philadelphia."

However, though mosquito-borne diseases have caused outbreaks in the past all the way up the East Coast, large outbreaks are less likely today because of changes in mosquito breeding sites and human behavior, he said.

In the U.S., most people spend most of their time indoors, in air-conditioned rooms with screened-in windows, with few opportunities to be bitten by the nasty bugs. What's more, there are relatively few pockets of standing water where the mosquitoes can breed, and mosquito control efforts are generally very good in the continental U.S., Monaghan said.

Mosquito hotspots

To identify the locations with the highest transmission risk, Monaghan and his colleagues looked at 50 major cities in the U.S. They analyzed data on climate; month-to-month models of Aedes aegypti abundance; air travel from Zika-affected regions; poverty levels, which correlate with a lower probability of having air conditioning and screened-in windows; and history of dengue and chikungunya, which are also transmitted by Aedes mosquitoes. (The team did not analyze data from Alaska or Hawaii. However, there is an active dengue outbreak on the Big Island of Hawaii, and the state is likely vulnerable to Zika transmission because of its combination of a tropical climate and a bevy of tourists, who are not as savvy about preventing mosquito bites, Monaghan noted.)

For most of the country, the risk of localized Zika transmission will remain very low until the summer, when Aedes aegypti populations rise, the study found.

The areas with the highest risk of Zika transmission are in south Texas and Florida — particularly, places like Miami, which has both the right climate for the mosquitoes to breed and an influx of travelers from Zika-affected areas, the researchers reported today (March 16) in the journal PLOS Currents Outbreaks.

However, even those areas are likely to experience at most a few dozen cases of local transmission, if history of chikungunya and dengue viruses is any indication, Monaghan said.

"We've seen local outbreaks that have been pretty small in Florida and south Texas," Monaghan said. These areas of the country already have active surveillance programs for dengue and chikungunya, and well-established mosquito-control efforts, he added.

However, public health officials in areas of moderate risk of Zika transmission — particularly in the U.S. Southeast — could consider implementing timed mosquito-control efforts, Monaghan said.

Still, the new model is just a first-pass estimate of Zika transmission, Monaghan said. It is limited, for instance, because the researchers looked only at the Zika-transmission risk associated with the mosquito species Aedes aegypti, even though the much more widespread species Aedes albopictus can also transmit the virus.

In addition, researchers still don't know whether the Zika virus is transmitted to people more easily than other similar mosquito-borne viruses, such as dengue virus, Monaghan said.

Follow Tia Ghose on Twitterand Google+. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Tia is the managing editor and was previously a senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.

New QPU benchmark will show when quantum computers surpass existing computing capabilities, scientists say

Pair of 'glowing' lava lakes spotted on Africa's most active volcanoes as they erupt simultaneously — Earth from space

Simple blood test could reveal likelihood of deadly skin cancer returning, study suggests