The Science of Hunger: How to Control It and Fight Cravings

Whether you're trying to lose weight, maintain weight loss or just stay healthy, at some point, you're going to get hungry. But simply eating whenever the urge strikes isn't always the healthiest response — and that's because hunger isn't as straightforward as you may think.

A complex web of signals throughout the brain and body drives how and when we feel hungry. And even the question of why we feel hungry is not always simple to answer. The drive to eat comes not only from the body's need for energy, but also a variety of cues in our environment and a pursuit of pleasure.

To help you better understand and control your hunger, Live Science talked to the researchers who have looked at hunger every which way, from the molecular signals that drive it to the psychology of cravings. Indeed, we dug into the studies that have poked and prodded hungry people to find out exactly what's going on within their bodies. We found that fighting off that hungry feeling goes beyond eating filling foods (though those certainly help!). It also involves understanding your cravings and how to fight them, and how other lifestyle choices — such as sleep, exercise and stress — play a role in how the body experiences hunger.

Here is what we found about the science of hunger and how to fight it.

Jump to section:

- What is hunger? Homeostatic vs. hedonic

- Controlling hunger in the short term – cravings

- Controlling hunger in the long term

- What about "hunger blocking" supplements?

What is hunger? Homeostatic vs. hedonic

Before we begin, it's important to understand exactly what hunger is — what's going on inside your brain and body that makes you say, "I'm hungry"?

As it turns out, feeling hungry can mean at least two things, and they are pretty different, said Michael Lowe, a professor of psychology at Drexel University in Philadelphia.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Of course, there's the traditional concept of hunger: when you haven't eaten in several hours, your stomach is starting to grumble and you're feeling those usual bodily sensations associated with hunger, Lowe said. This feeling of hunger stems from your body's need for calories; the need for energy prompts the signal that it's time to eat, he said.

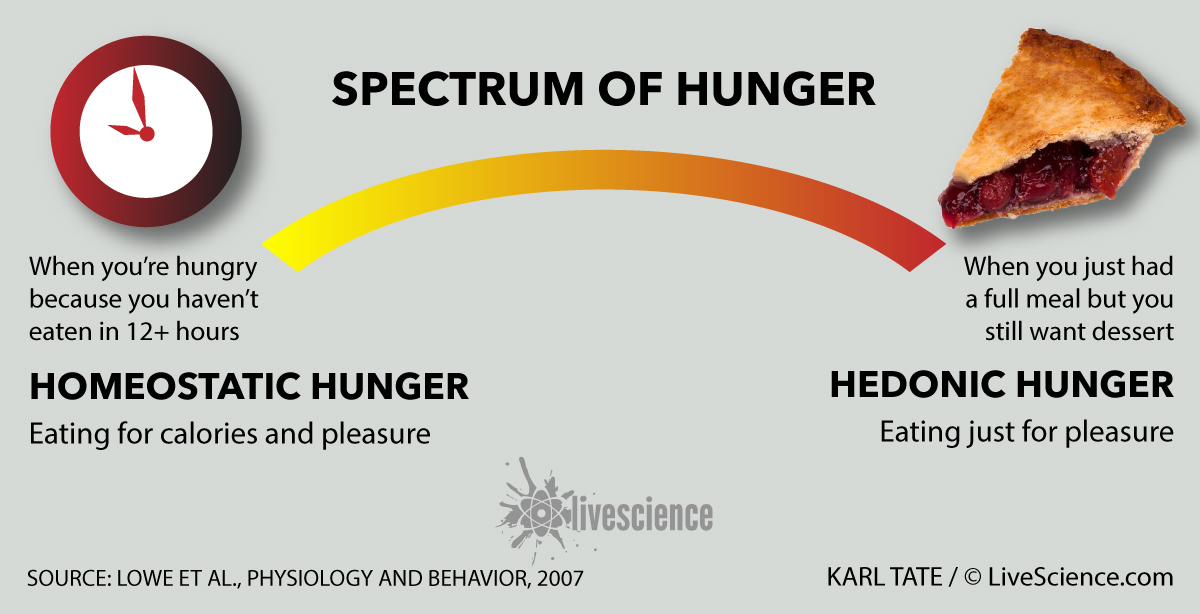

Researchers refer to this type of hunger as "homeostatic hunger," Lowe told Live Science.

Homeostatic hunger is driven by a complex series of signals throughout the body and brain that tell us we need food for fuel, said Dr. Amy Rothberg, director of the Weight Management Clinic and an assistant professor of internal medicine in the University of Michigan Health System's Division of Metabolism, Endocrinology and Diabetes.

Hormones in the body signal when energy stores are running low. When this occurs, levels of ghrelin (sometimes referred to as the "hunger hormone") start to rise, but then become suppressed as soon as a person starts eating, Rothberg said. In addition, as food travels through the body, a series of satiety responses (which signal fullness) are fired off, starting in the mouth and continuing down through the stomach and the small intestine, she said. These signals tell the brain, "Hey, we're getting food down here!"

And up in the brain, another series of signals is at work, Rothberg said. These are the sets of opposing signals: the hunger-stimulating ("orexigenic") peptides, and the hunger-suppressing ("anorexigenic") peptides, she said. These peptides are hormones that are responsible for telling the brain that a person needs to eat or that a person feels full.

Unsurprisingly, the best way to get rid of homeostatic hunger is to eat. And your best bet to maintain that full feeling for a healthy amount of time is to eat nutritious foods that, well, fill you up, Rothberg told Live Science. [Diet and Weight Loss: The Best Ways to Eat]

A diet that contains fiber and lean protein is very filling, Rothberg said. And protein is the most filling of the macronutrients, she said. Indeed, a recent meta-analysis study in the Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics concluded that eating larger amounts of protein does increase feelings of fullness compared to eating smaller amounts of protein. [Which Types of Foods Are The Most Filling?]

But it's also important to be careful about certain foods. Zero-calorie sweeteners, for example, can confuse fullness signals and trick your brain into thinking you haven't eaten much when you actually have, thus leading you to eat more, Rothberg said. (There is much debate among health experts about the effects of these sweeteners in the body. For example, although they may help people control their blood sugar levels, evidence is mixed on whether they help people lower their calorie intake or lose weight. In our interview with her, Rothberg was referring specifically to how zero-calorie sweeteners may impact feelings of hunger and fullness.)

Another food group to be careful about is ultraprocessed foods, which are loaded with fat and sugar. People don't just eat for calories, they eat for pleasure, but foods like these can drive the brain to want more of them, essentially overpowering the normal fullness signals firing in the brain, Rothberg said.(Ultraprocessed foods are those that, in addition to sugar, salt, oils and fats, include additives like emulsifiers, flavors and colors — think potato chips or frozen pizza.)

Of course, if people only ate because their bodies needed calories, things would be simple. But that's not the case.

People "don't eat necessarily because of the signals that govern our energy stores," Rothberg said. Rather, sometimes, you just want food.

This type of hunger is called "hedonic hunger." But hedonic hunger — wanting to eat, dwelling on food or maybe craving something — isn't nearly as well understood as homeostatic hunger, Lowe said. The term "hedonic hunger" was coined in 2007 in a review led by Lowe and published in the journal Physiology & Behavior.

The most widely accepted theory about hedonic hunger is that the human predisposition to highly palatable foods, which humans developed long ago, has run amok in the modern environment, with the wide availability of really delicious foods, Lowe said. People want to eat even when they don't need to, he said. And the more often people eat highly palatable foods, the more their brains learn to expect and want them, he said. You can call that hunger, but the reason for that "hungry" feeling appears to have much more to do with seeking pleasure than with needing calories, he said.

But it's important for people to realize that pleasure plays a role in all types of eating, Lowe said. Pleasure is relevant to both homeostatic and hedonic eating, whereas the need for calories only comes into play during homeostatic eating, he said. For example, when someone is homeostatically hungry, that person is motivated by both the calories and the pleasure that eating brings, he said. Someone who is hedonically hungry, on the other hand, is motivated only by pleasure, he said.

The two types of hunger are not completely distinct but rather represent two ends of a continuum, Lowe said. Certainly, there are cases of hunger that fall at each end of the spectrum: A person who hasn't eaten in 12 or more hours is experiencing homeostatic hunger, whereas a person who wants dessert after finishing a filling meal is experiencing hedonic hunger. But there isn't a specific point where someone could say their hunger has switched from being motivated by calories to being motivated purely by pleasure, he said.

Even if a person can recognize whether their hunger is more of a hedonic hunger than a homeostatic hunger, hedonic hunger can still be a little harder to fight.

The best practice for fighting hedonic hunger is to keep those highly palatable, tempting foods out of the house, Lowe said. But if you don't want to clear your pantry, another tip is to try to curb the desire by eating something "less damaging" — for instance, a piece of fruit instead of a piece of candy — and then seeing if you still want something sweet, he said.

Finally, keeping treats in portion-controlled servings also may help, Lowe said. For example, instead of keeping a half gallon of ice cream in the freezer, buy chocolate ice pops or ice cream sandwiches, and eat just one, he said.

Controlling hunger in the short term – cravings

The "desire" to eat may sound similar to cravings, and there's definitely overlap between the two. However, a craving is a desire for a specific food, whereas hedonic hunger is a desire for palatable foods in general, Lowe said.

Jon May, a professor of psychology at Plymouth University in the United Kingdom, agreed that food cravings are a part of hunger.

But the way a person ultimately responds to feelings of hunger determines whether a craving develops, May told Live Science. One theory of how cravings develop is called the elaborated intrusion theory, which was first proposed by May and colleagues in a 2004 paper in the journal Memory.

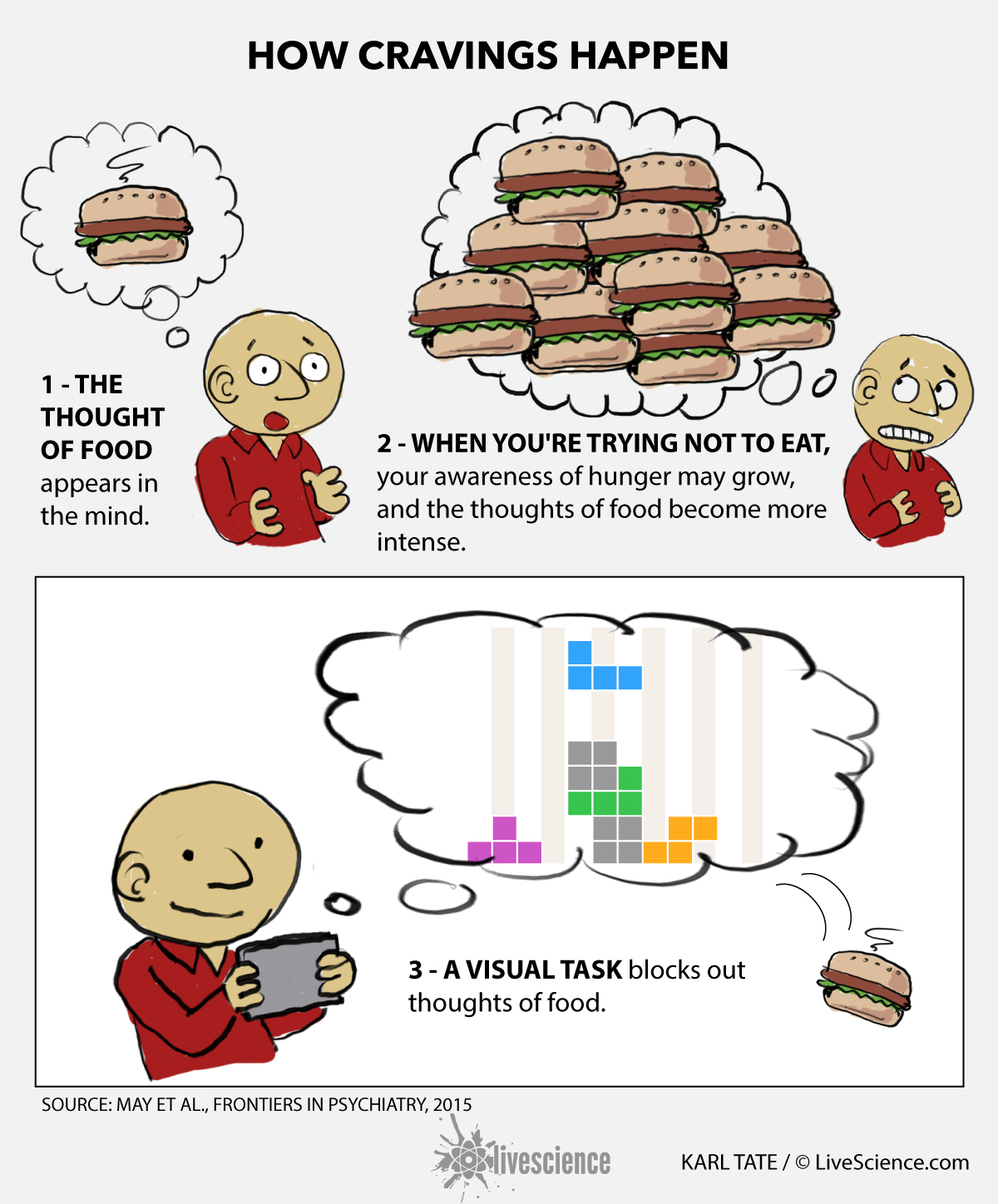

To understand the elaborated intrusion theory and how it applies to food cravings, consider this: People aren't always aware that they are hungry until the feelings become very strong, or until a person has nothing else to attend to, and thus an awareness of hunger comes to the forefront of their attention, May said. For example, when you're working really hard to finish a project at work and it's finally done, you realize you're hungry. "This transition from unconscious to conscious makes the hunger seem very important, so we attend to it — and we call this an intrusive thought," he said.

If a person then were to go and eat something, the thought would be handled, and there would be no need to crave or desire anything, May said. But if a person did not eat, they may dwell on that intrusive thought. Perhaps they would imagine the sight, smell and taste of the food, think about where they could get some of it, and so on, May said. Because thinking about foods is pleasant, we continue to do so, making our awareness that we're hungry (and still not eating) worse and worse, he said. By elaborating on the initial intrusive thought, the person has developed a craving, he said.

Imagining foods in greater detail can lead to emotional responses that further fuel cravings, May said. In fact, research has shown that visualizing foods plays such a strong role in cravings that even asking people to picture a food can trigger a craving, he said.

So, to stop a craving, your best bet is to thwart the mental processes needed to imagine food, he said. And thinking about other visual imagery is a good place to start.

In a growing body of research, May has looked at fighting hunger by engaging the brain in other tasks. "We've used a variety of tasks, ranging from direct instructions, to imagining scenes that are not associated with food, to making shapes out of clay without looking at your hands, [to] playing 'Tetris,' where you have to visualize the shapes rotating and fitting into gaps," May told Live Science. "'Tetris' is great because it is so fast-paced that you have to visualize shape after shape," he added.

Ultimately, "the more a task requires continual visual imagery, the more it will reduce a craving" because "the food images cannot sneak" into your mind, May said.

Of course, individual cravings are brief and can vary in intensity, May said. While a person can resist a craving by stopping the mental elaboration, it's still possible that a new craving will pop up a few minutes later, he said.

But studies have shown that trying these specific tasks may reduce the intensity of people's cravings as well as the amount they eat. For example, in a 2013 study published in the journal Appetite, researchers found that women who looked at a smartphone app that showed a rapidly changing visual display whenever they had a craving reported that the craving became less intense. What's more, they also consumed fewer calories over a two-week period. In another, shorter study, researchers found that asking college students to vividly imagine engaging in a favorite activity when a craving struck reduced the intensity of those cravings over a four-day period.

"Just knowing how cravings start and stop can help you let them fade away without having to react to them," May said. "Most cravings fade by themselves if you can resist them, but if you need help to bolster your willpower," visualizing a familiar, pleasant scene can help, as can fiddling with something out of sight and concentrating on making shapes without looking at them, he said.

Since May first proposed the elaborated intrusion theory in 2004, a number of other researchers have explored the theory, and there's a growing amount of evidence to support it. In 2015, May wrote a retrospective detailing how the theory caught on in the world of cravings and addiction research.

Controlling hunger in the long term

Beyond our in-the-moment thoughts about food, the mechanisms in our bodies that regulate hunger are complex. Indeed, many factors beyond the foods we tend to eat on a daily basis can influence these mechanisms. These factors include sleep, exercise and stress.

Sleep

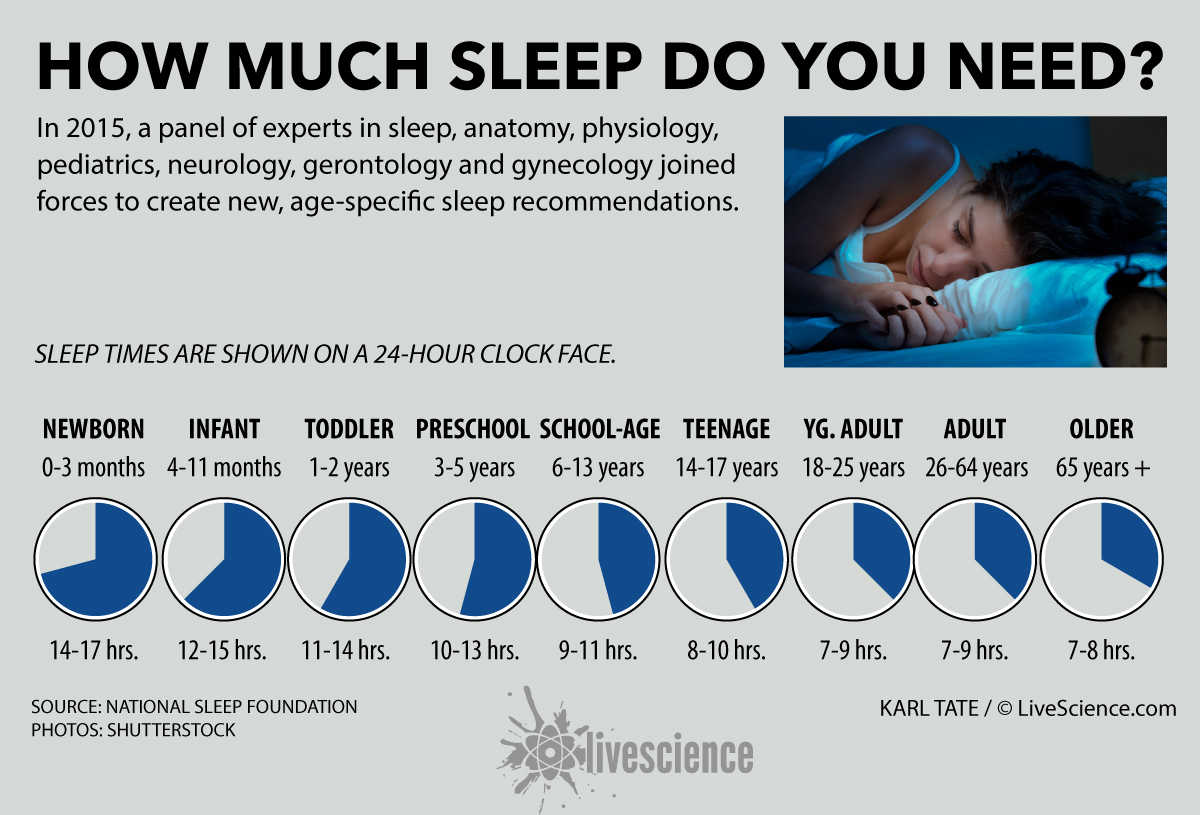

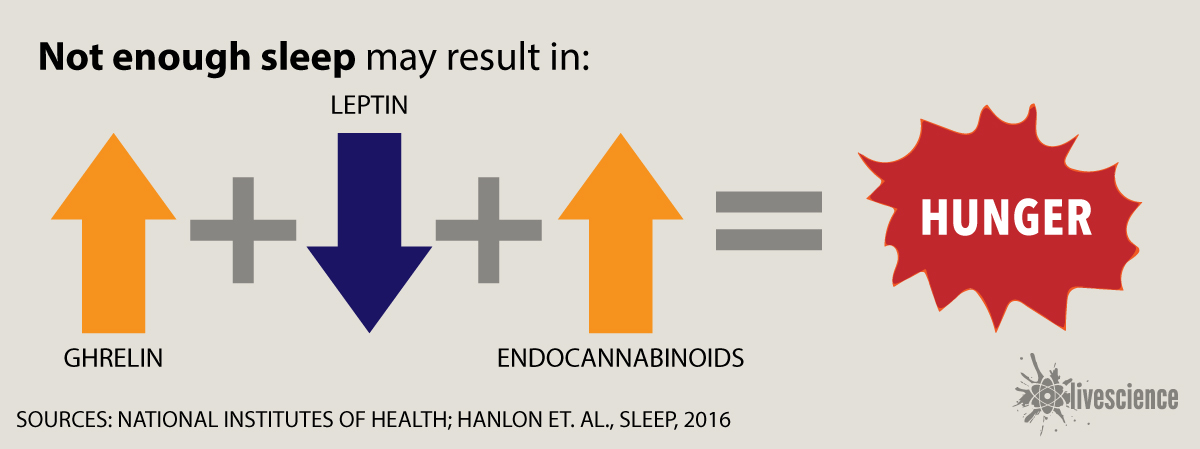

Much research has shown that not getting enough sleep increases hunger, said Erin Hanlon, a research associate in endocrinology, diabetes and metabolism at the University of Chicago. For example, sleep restriction may lead to increases in ghrelin and decreases in leptin, according to the National Institutes of Health.

Shifts in leptin and ghrelin levels are thought to be involved more in homeostatic hunger, but there's growing evidence that sleep deprivation also may increase hedonic hunger, she said.

Researchers know that when people's sleep is restricted, they report higher levels of hunger and appetite, Hanlon said. But studies in laboratories have shown that sleep-deprived people seem to eat well beyond their caloric needs, suggesting that they're eating for reward and pleasure, she said.

For example, Hanlon's February 2016 study, published in the journal Sleep, looked at one measurable aspect of hedonic eating: levels of endocannabinoids in the blood. Endocannabinoids are compounds that activate the same receptors as the active ingredient in marijuana does, leading to increased feelings of pleasure. Endocannabinoid levels normally rise and fall throughout the day and are linked with eating. However, it's unclear whether these compounds drive a person to eat or if, once a person starts eating, make it harder for him or her to stop, Hanlon said.

The researchers found that in a 24-hour period following sleep deprivation (in which people slept 4.5 hours rather than 8.5 hours), the levels of endocannabinoids peaked later in the day, and also stayed elevated for longer periods of time, than they did when people were not sleep deprived. Those peaks coincided with other measurements in the study, including when people reported being hungry and having increased desires to eat, and also when they reported eating more snacks, according to the study. Overall, the results of the study add further evidence to suggest that insufficient sleep plays an important role in eating and hunger, the researchers said.

But although there's growing evidence to suggest that not getting enough sleep increases both types of hunger, there's still the question of whether the reverse is true, too — namely, if people get more sleep, will they be less hungry?

Researchers have only just started looking into that question, Hanlon said. For example, some research has suggested that increasing sleep time may reduce cravings for certain foods, she said. But so far, most of these "sleep extension" studies have focused more on how sleep affects blood sugar levels than on which foods people choose and how much they eat, she said. Therefore, more research is needed to answer these questions.

Exercise

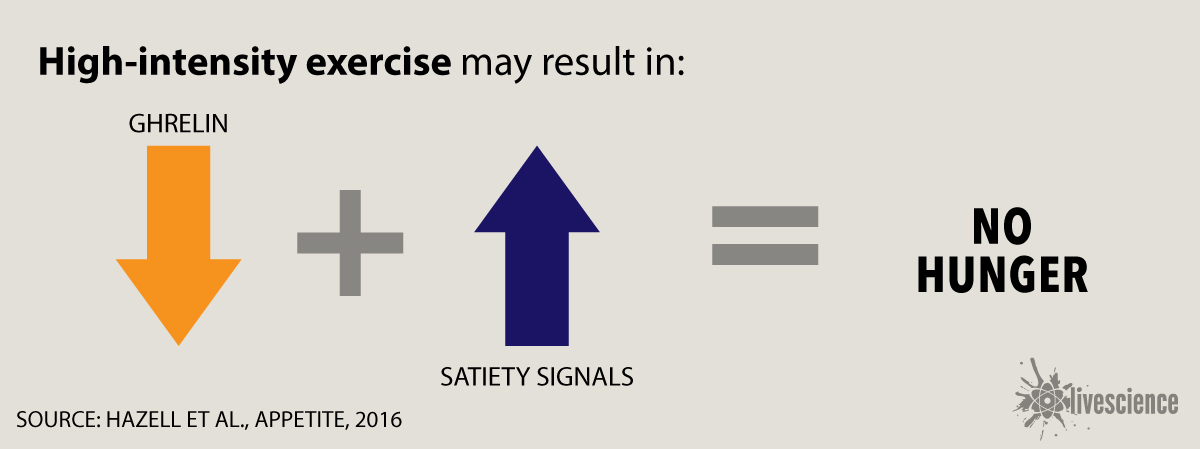

To anyone who's ever felt ravenous after working out, the idea that exercise can suppress appetite may sound counterintuitive. But some research suggests that certain types of physical activity — namely, a short, intense workout — may suppress levels of the hormones known to drive appetite.

Based on the scientific literature, "it certainly seems that exercise would decrease the appetite-stimulating hormone ghrelin," said Tom Hazell, an assistant professor of kinesiology and physical education at Wilfrid Laurier University in Canada. (However, not all studies on this topic have shown this effect, he added.) Exercise also appears to increase levels of other hormones, such as cholecystokinin and peptide YY, which play a role in inhibiting appetite, Hazell told Live Science. However, more research into precisely how exercise affects the suppression and release of these hormones is needed, he said. This is still a relatively new topic of research, he added.

But not all types of exercise appear to have the same effect. Most people actually feel hungrier after doing low- to moderate-intensity exercise, Hazell said, and this is the preferred type of workout for many people. [How to Make Sense of Heart Rate Data]

It seems logical that the body would try to replenish the energy it used during exercise, and when the intensity is low to moderate, it's relatively easy to do so after exercise, Hazell said. In other words, to restore balance, the body wants to eat food to replace the calories it just burned. But, in contrast, when someone does a high-intensity workout, the body experiences many more changes in metabolism than just losing calories, he said. So although the body does want to replenish its energy stores, it prioritizes dealing with these other changes before doing so, he said.

All of this begs the question, if you're feeling hungry, could exercise possibly squash the feeling?

"I think if the person were hungry and performed an exercise session of sufficient intensity, there would still be a benefit by reducing hunger," Hazell said. Exercising around times when you know hunger tends to strike "could be an interesting preemptive option too," he added, though this idea has not yet been looked at in a formal study. [Best Fitness Trackers 2016]

Stress

When it comes to factors that influence eating, it's hard to ignore good old stress eating. But different types of stress can have different effects on different people, said Dr. Michael Lutter, a psychiatrist at the University of Iowa. [5 Tips to Reduce 'Stress Eating']

Major stressors — such as war, famine and severe trauma — are associated with an increased risk of developing serious mental illnesses, such as major depression and post-traumatic stress disorder, both of which have been linked to changes in appetite, said Lutter, who has researched the neurological basis of feeding and disordered eating.

But the data on whether mild stressors — the kinds people experience on a day-to-day basis — can trigger hunger is less clear, Lutter said. In surveys, about 40 percent of people report that they eat in response to stress, but another 40 percent say they experience a decrease in their appetite in response to stress, he said. As for the remaining 20 percent? They report no effect, Lutter said.

It's also unclear what's going on in the body to drive stress-induced eating. "Historically, cortisol [the stress hormone] has been primarily linked to stress-induced eating," Lutter said. But this link was based on research showing that high levels of cortisol — resulting from either medication or an illness — could affect metabolism, he said. Mild stress also causes cortisol levels to rise acutely; but these increases are much smaller and do not last as long, so it's not entirely clear how much "stress-induced" changes in cortisol drive comfort eating, he said.

Rather, "ghrelin, and possibly leptin, also likely contribute to changes in food intake and body weight in response to chronic stress," Lutter said. However, the strongest data for this is in mice, not in humans, he added.

For people who want to reduce "stress eating," mindfulness-based approaches are probably the best studied. However, the evidence in this area isn't overwhelming, Lutter said. ("Mindfulness" is when a person learns to be aware of what he or she is feeling physically and mentally from moment to moment.) But in addition to mindfulness, keeping a journal of what you eat is another approach that may help you monitor the way food intake relates to changes in emotions.

What about "hunger blocking" supplements?

A quick Internet search for "appetite suppressing supplements" yields plenty of results, but are any of these pills worth purchasing? The answer, in short, is no, said Melinda Manore, a professor of nutrition at Oregon State University.

Although there is some evidence that some of these supplements may suppress appetite, any effect seen may not be very pronounced, Manore noted. Compared to when a person takes a placebo, he or she may see 2 or 3 lbs. (0.9 to 1.4 kilograms) of weight loss while taking certain types of supplements, she said, noting that most people expect to see more drastic results.Many of the over-the-counter appetite suppressants, which aim to blunt appetite-stimulating hormones, are really just stimulants, Manore told Live Science. And although researchers have found that these supplements can suppress appetite a bit, they are dangerous because they're not regulated, she said. In addition, supplement companies often "stack" stimulants — meaning they combine several ingredients into one supplement — and these types of supplements should be avoided entirely, Manore said.

For example, two popular supplements aimed at fighting hunger to aid in weight loss are soluble fiber, and an extract from a type of cactus called Hoodia gordonii. In a 2012 review of studies published in the International Journal of Sport Nutrition and Exercise Metabolism, Manore looked at all of the available evidence about these supplements. She found that although a high-fiber diet has been shown to aid in weight loss, the evidence for supplementing a diet with fiber is more equivocal, and may depend on the type and amount of fiber used, according to the review. Moreover, there was no evidence from human studies showing that Hoodia gordonii suppresses appetite, Manore wrote.

Ultimately, although some products show modest effects, many supplements have had either no or limited randomized, controlled trials to examine their effectiveness, Manore wrote. "Currently, there is no strong body of research evidence indicating that one specific supplement will produce significant weight loss," especially in the long term, she wrote in her conclusion.

Follow Sara G. Miller on Twitter @SaraGMiller. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook& Google+. Originally published on Live Science.