Tesla Coils 'Sing' in Electrifying Performance

WASHINGTON — When most people rave about seeing an "electrifying" performance, they typically aren't talking about witnessing real lightning on stage. But for the band ArcAttack, harnessing the power of 1 million volts of electricity — and turning that energy into music — is business as usual.

ArcAttack creates music using two giant structures called Tesla coils, which were invented by the eccentric genius Nikola Tesla in 1891, as part of his dream to develop a way to transmit electricity around the world without any wires. Now, more than 120 years later, a band that is described by its founding member, Joe DiPrima, as a "mad scientist-slash-rock group," has found an innovative way to use these tower-like structures for entertainment.

The band performed Saturday (April 23) here at Smithsonian magazine's "The Future Is Here" festival, a three-day event that explores the intersection of science and science fiction. [Science Fact of Fiction? The Plausibility of 10 Sci-Fi Concepts]

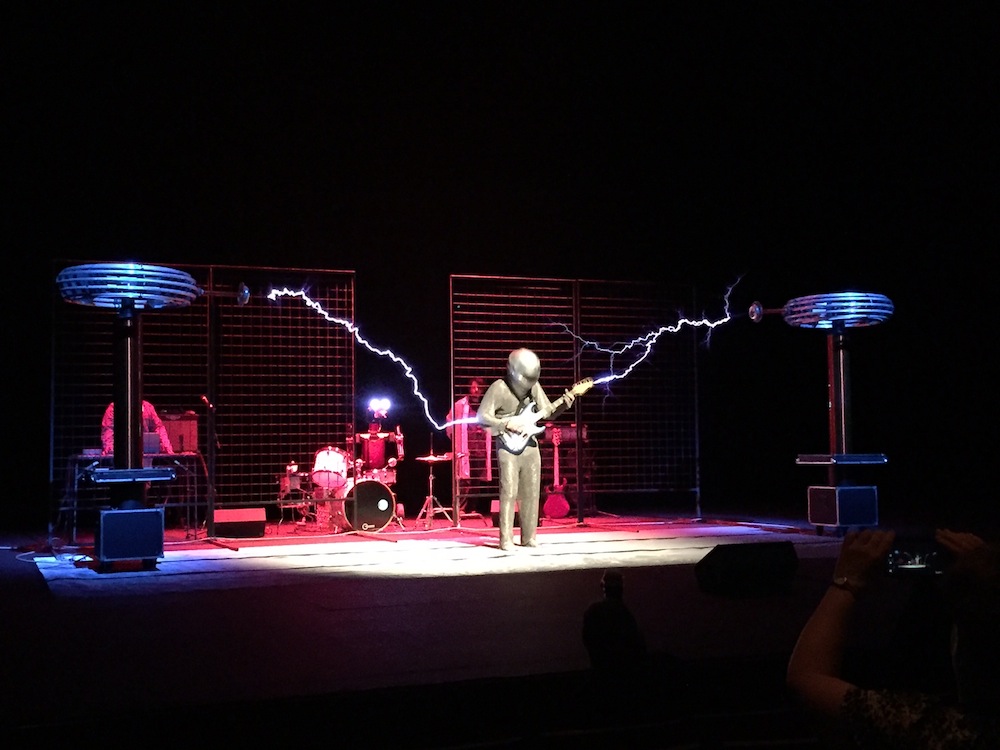

When they are played, the Tesla coils emit a soft buzz before unleashing long tentacles of electricity. These sparks not only serve as a dramatic way to light up the stage, but also "sing" musical notes by causing air molecules to vibrate, creating sound waves. A bass guitarist typically accompanies the coils; during part of Saturday's performance, he donned a metal suit and protective helmet, and stood between the two coils, playing a guitar as giant sparks lapped at the custom-made, lightning-proof instrument.

Tesla invented his coil to do things like light up fluorescent bulbs without any connecting wires, but ArcAttack's coils feature a slightly more modern design, making use of some components that weren't available in the 1890s. But overall, Tesla's original invention remains mostly unchanged, according to the band.

ArcAttack's Tesla coils have been "engineered in such a way that they play music," DiPrima said. "The main tones you're hearing are from the spark itself."

The Tesla coils consist of a primary coil and a secondary coil, each with a capacitor to store electrical energy and an inductor that resists changes in the electric current passing through.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

ArcAttack's system takes low-voltage energy from a power source and then "steps it up" to a high voltage with a transformer. The devices store energy by vibrating at their natural frequency, and when the entire system is up and running, the primary and secondary coils can pass energy back and forth between each other. Eventually, the voltage at the top of the structure gets so high that it needs to burst out as an electric current. For the coils to play musical notes, though, DiPrima and his bandmates control the current and resulting sparks, toying with the frequencies so that the audience perceives the "pops" as pitches.

In 2010, ArcAttack competed on the reality show "America's Got Talent," performing in the semifinals before they were eliminated. Now, the Austin, Texas-based band tours the country, doing live performances and educational outreach, such as making their equipment available to science museums, according to the group's website.

Working with electricity obviously requires rigorous safety provisions, but DiPrima, who used to work as a television repairman, said the singing Tesla coils are safer than people might expect.

"I've shocked myself with televisions way more," he said.

Follow Denise Chow on Twitter @denisechow. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Denise Chow was the assistant managing editor at Live Science before moving to NBC News as a science reporter, where she focuses on general science and climate change. Before joining the Live Science team in 2013, she spent two years as a staff writer for Space.com, writing about rocket launches and covering NASA's final three space shuttle missions. A Canadian transplant, Denise has a bachelor's degree from the University of Toronto, and a master's degree in journalism from New York University.