5,000-Year-Old Chinese Beer Recipe Had Secret Ingredient

Barley might have been the "secret ingredient" in a 5,000-year-old beer recipe that has been reconstructed from residues on prehistoric pots from China, according to new archaeological research.

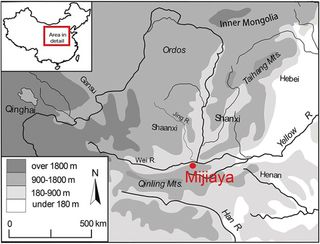

Scientists conducted tests on ancient pottery jars and funnels found at the Mijiaya archaeological site in China's Shaanxi province. The analyses revealed traces of oxalate — a beer-making byproduct that forms a scale called "beerstone" in brewing equipment — as well as residues from a variety of ancient grains and plants. These grains included broomcorn millets, an Asian wild grain known as "Job's tears," tubers from plant roots, and barley.

Barley is used to make beer because it has high levels of amylase enzymes that promote the conversion of starches into sugars during the fermenting process. It was first cultivated in western Asia and might have been used to make beer in ancient Sumer and Babylonia more than 8,000 years ago, according to historians. [See Photos of Ancient Beer Brewing in China's 'Cradle of Civilization']

The researchers said it is unclear when beer brewing began in China, but the residues from the 5,000-year-old Mijiaya artifacts represent the earliest known use of barley in the region by about 1,000 years. They also suggest that barley was used to make beer in China long before the cereal grain became a staple food there, the researchers noted.

Surprising ingredient

The prehistoric brewery at the Mijiaya site consisted of ceramic pots, funnels and stoves found in pits that date back to the Neolithic (late Stone Age) Yangshao period, around 3400 to 2900 B.C., said Jiajing Wang, a Ph.D. student at Stanford University in California and lead author of a new paper on the research, published today (May 23) in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Wang told Live Science that the discovery of barley in such early artifacts was a surprise to the researchers.

Barley was the main ingredient for beer brewing in other parts of the world, such as in ancient Egypt, she said, and the barley plant might have spread into China along with the knowledge of its special use in making beer.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"It is possible that when barley was introduced from western Eurasia into the Central Plain of China, it came with the knowledge that the grain was a good ingredient for beer brewing," Wang said. "So it was not only the introduction of a new crop, but also the knowledge associated with the crop."

The ancient art of beer

The Mijiaya site was discovered in 1923 by Swedish archaeologist Johan Gunnar Andersson, Wang said. The site, located near the present-day center of the city of Xi'an, was excavated by Chinese archaeologists between 2004 and 2006, before being developed for modern residential buildings.

After the full excavation report was published in 2012, Wang's co-author on the new paper, archaeologist Li Liu of Stanford, noticed that the pottery assemblages from two of the pits could have been used to make alcohol, mainly because of the presence of funnels and stoves.

Wang said that some Chinese scholars had suggested several years ago that the Yangshao funnels might have been used to make alcohol, but there had been no direct evidence until now. [Raise Your Glass: 10 Intoxicating Beer Facts]

In the summer of 2015, the Stanford researchers traveled to Xi'an and visited the Shaanxi Institute of Archaeology, where the artifacts from the Mijiaya site are now stored.

The scientists extracted residues from the artifacts, and their analysis of the residues turned out to prove their hypothesis: that "people in China brewed beer with barley around 5,000 years ago," Wang said.

Reconstructing the recipe

The researchers found yellowish remnants in the wide-mouthed pots, funnels and amphorae that suggested the vessels were used for beer brewing, filtration and storage. The stoves in the pits were probably used to provide heat for mashing the grains, according to the archaeologists.

The beer recipe used a variety of starchy grains, including barley, as well as tubers, which would have added starch for the fermentation process and sweetness to the flavor of the beer, the researchers said.

Wang and her co-authors wrote that barley had been found in a few Bronze Age sites in the Central Plain of China, all dated to around or after 2000 B.C. However, barley did not become a staple crop in the region until the Han dynasty, from 206 B.C. to A.D. 220, the researchers said.

"Together, the lines of evidence suggest that the Yangshao people may have concocted a 5,000-year-old beer recipe that ushered the cultural practice of beer brewing into ancient China," the archaeologists wrote in the paper. "It is possible that the few rare finds of barley in the Central Plain during the Bronze Age indicate their earlier introduction as rare, exotic food."

"Our findings imply that early beer making may have motivated the initial translocation of barley from western Eurasia into the Central Plain of China before the crop became a part of agricultural subsistence in the region 3,000 years later," the researchers wrote.

It's even possible that beer-making technology aided the development of complex human societies in the region, the researchers said. "Like other alcoholic beverages, beer is one of the most widely used and versatile drugs in the world, and it has been used for negotiating different kinds of social relationships," the archaeologists wrote.

"The production and consumption of Yangshao beer may have contributed to the emergence of hierarchical societies in the Central Plain, the region known as 'the cradle of Chinese civilization,'" they added.

Follow Tom Metcalfe @globalbabel. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Tom Metcalfe is a freelance journalist and regular Live Science contributor who is based in London in the United Kingdom. Tom writes mainly about science, space, archaeology, the Earth and the oceans. He has also written for the BBC, NBC News, National Geographic, Scientific American, Air & Space, and many others.

Most Popular