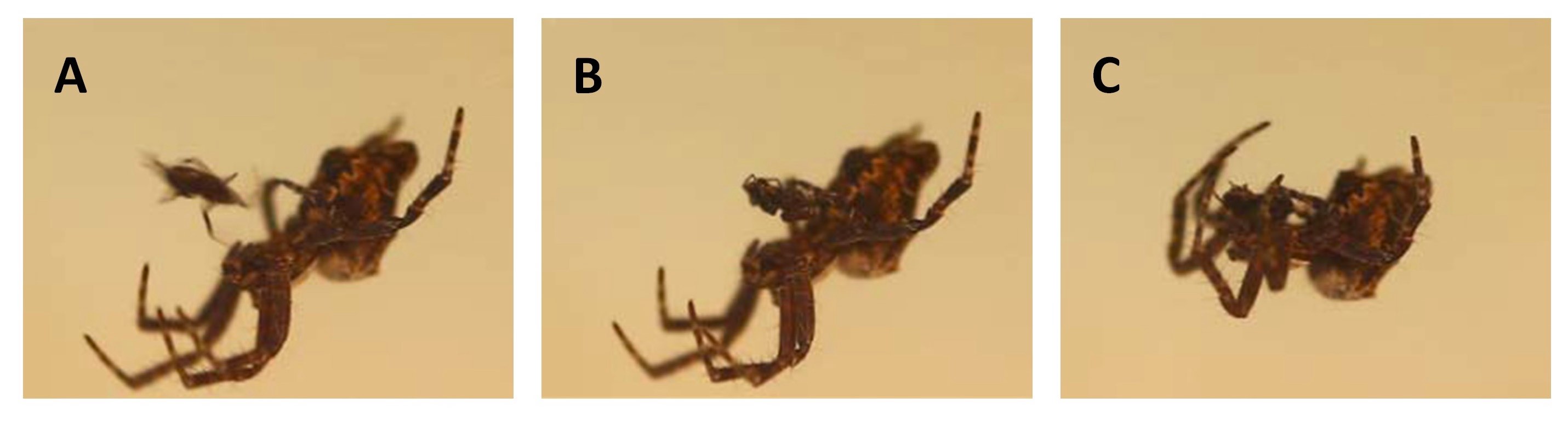

Male Orb-Web Spiders Are Choosy About Their Cannibal Mate

Male colonial orb-web spiders almost always get eaten by females right after mating. But perhaps it's a consolation that they get to choose their cannibal.

New research finds that, in a reversal from many species, it's male orb-web spiders, not females, that are choosy about their mates. This pickiness likely evolved because most males get only one chance at mating before they're eaten, Eric Yip, a spider ecologist at Ben-Gurion University of the Negev in Israel, and colleagues wrote in the open-access journal PLOS ONE.

"With over 80 percent of males cannibalized after their first copulation, males need to make their one shot at paternity count," Yip said in a statement. [See Video of the Deadly Spider Courtship]

One shot

Generally, females are pickier about mates than males are because eggs are more energy-intensive than sperm to produce (and gestate). But in cannibalistic species, the sex roles could be reversed, Yip and his colleagues reasoned. If males mate only once, and if they have the option to pick from multiple receptive females, it makes sense that they'd be choosy.

The researchers first placed some females into three groups and allowed each to mate. Then, after three and 10 days, respectively, they re-exposed two of the groups to new males. The females remated, meaning that although males are limited to one mating session because they're consumed immediately afterward, females are free to get busy again and again.

Next, the researchers exposed male spiders to female spiders that were either subadults, adult virgins or previously mated adults. They found that the males preferred the virgin adult females to the subadults or previously mated adults, both of which might not result in successful fertilization. Clearly, the males were savvy to their chances of siring offspring based on their mate's reproductive status. In addition, males courted younger females more often than older females.

Hungry, hungry spiders

The researchers also reared both males and females in low- and high-food conditions to create populations of plump, well-fed spiders and smaller, less fertile ones. Then, they mixed and matched male and female spiders from each feeding condition, to see if nutritional status and body size made a difference in mate choice.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

They found that the males were able to mate regardless of their nutritional status or body size, whereas the big females were twice as likely to mate as their underfed counterparts. Small females weren't less likely to mate because they were rejecting males, the researchers observed. Instead, most often, the males would abandon the courtship with smaller females. What's more, the males' mating behavior did not seem motivated by attempts to avoid being cannibalized, because both well-fed and poorly fed females ate their mates at the same rate.

Males don't try to escape before they're eaten, Yip and his colleagues wrote. As strange as it sounds, cannibalism may present an advantage to male spiders. Researchers aren't sure what that advantage might be in the case of colonial orb-web spiders, but possibilities include longer mating time, more sperm transfer or even the setting of some sort of secretion in the female that prevents future mating attempts.

The findings reveal how sexual cannibalism can prompt male choosiness to evolve, the researchers concluded.

"In a colony, males are likely to encounter multiple receptive females, and we found that males prefer to court and mate with younger, fatter and, therefore potentially more fecund, females," Yip said.

Original article on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.