Tomb with a View: Ancient Burial Sites Served as 'Telescopes'

Thousands of years ago, stone constructions built as tombs may have served another purpose — one with an unexpected celestial connection. Astronomers suggest these ancient structures may have been used for observing the night sky and tracking the movements of the stars.

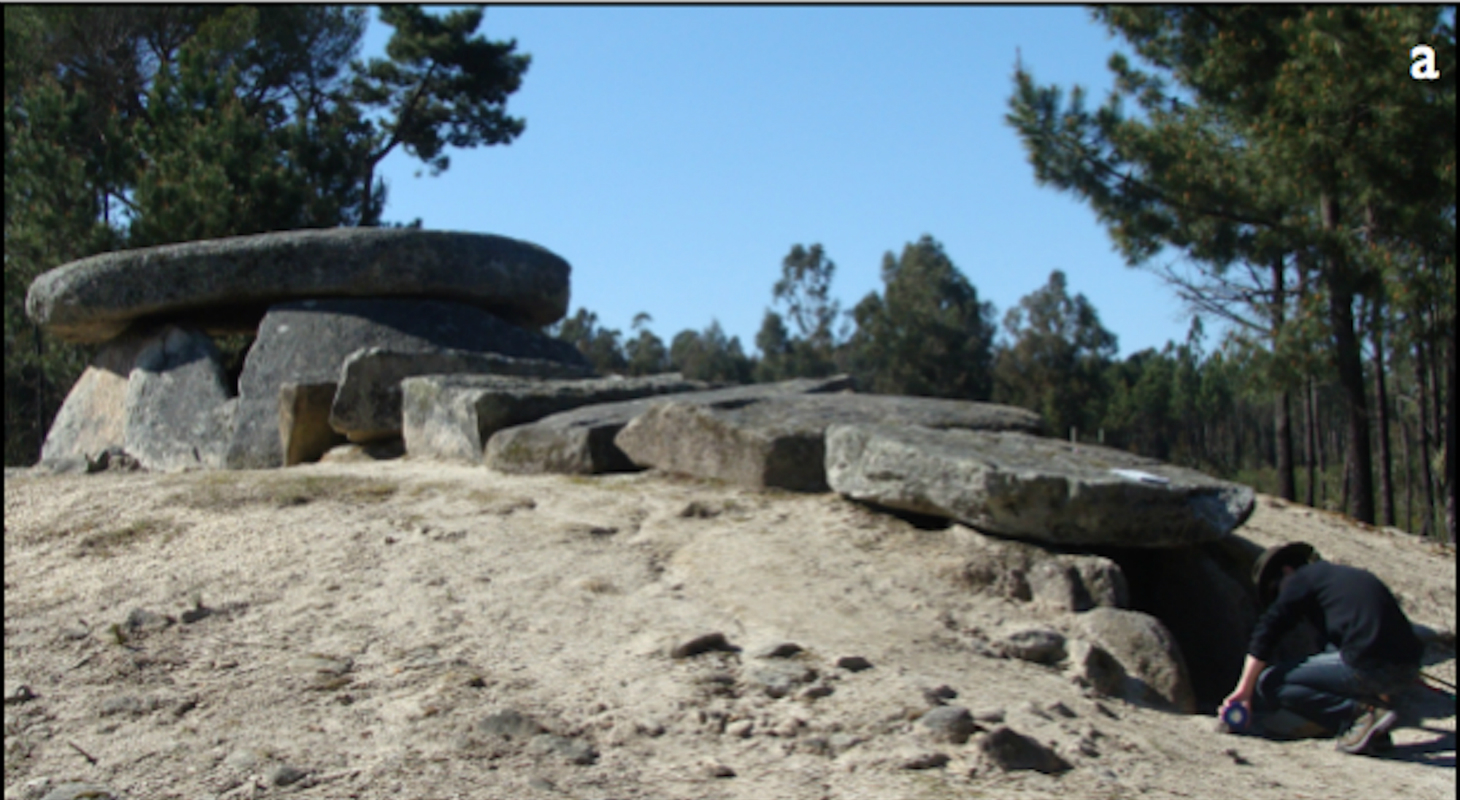

Researchers are investigating whether so-called "megalithic" tombs — tombs hewn from ancient stone — provided optical opportunities for humanity's earliest astronomers, acting as "telescopes" without lenses.

And the scientists are looking especially closely at passage graves, a type of tomb with a large chamber accessed through a long and narrow entry tunnel. This type of structure could have greatly enhanced views of faint stars as they rose on the dawn horizon. [Image Gallery: World's Oldest Astrologer's Board]

The findings were presented June 29 at the Royal Astronomical Society's (RAS) National Astronomy Meeting 2016 in Nottingham, in the United Kingdom. They were presented in a special session addressing how cultures and societies have been shaped by studying the sky, and vice versa.

The orientation of some passage graves is known to align with the positions of certain stars, according to study presenter Fabio Silva, a lecturer in cultural astronomy at the University of Wales Trinity Saint David in the United Kingdom.

Silva said in a statement that the Seven-Stone Antas, a 6,000-year-old monolithic cluster in central Portugal, was constructed so that the entrance might align with the star Aldebaran, "the brightest star in the constellation of Taurus." He added that ancient societies would have found it vital to detect stars during twilight hours in order to accurately time the objects' first appearances at specific times of the year. This may have informed people's decisions about seasonal migrations to summer hunting grounds, Silva said.

Light at the end of the tunnel

Passage graves are thought to be sacred spaces in ancient societies, said Daniel Brown, a senior lecturer in astronomy at Nottingham Trent University in the United Kingdom and organizer of the RAS session.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Brown told Live Science in an email that most passage graves in Western Europe date from 6000 B.C. to 2000 B.C. and they were widespread along the Atlantic coast of Europe.

"Different regions had their own traditions and architectural styles, but they are all variations on a theme," Brown said. "In most circumstances, the evidence suggests the inner megalithic chamber(s) were used for burials or bone deposition, whereas outer courts might have been used for more communal practices — possibly related to the funerary rites."

In addition to housing the deceased, the tombs' inner chambers would sometimes host living individuals, who would spend the night inside the structures' walls as part of a rite of passage, the study presenters said.

The only natural light would filter from the opening at the far end of the tomb's entry tunnel, and the researchers suggested that this setup would have allowed a person within the chamber to observe faint stars in the night sky that might not be visible to someone standing outside. Tombs thus enabled stargazing thousands of years before the first telescopes were invented.

"Enhanced observing"

"The entrance creates an aperture as large as 10 degrees through which your naked-eye view is restricted," Brown explained. "This would allow enhanced observing, especially in the twilight hours of dusk and dawn."

According to Brown, the long and narrow entryway focused the viewers on a narrow strip of the horizon, in which faint stars could be rising at the same time that the sun rose or set. A restricted field of view would also limit the amount of light that could wash out the sky and make faint stars hard to see.

And after spending the night inside the tomb, a person's eyes would become used to lower light levels, and therefore better able to glimpse a dimmer star, Brown added.

Investigating the ways that early cultures used cosmology offers insights into how they understood the world around them, "as well as their place in it," Brown told Live Science.

"It also gives us an insight that astronomy as such did not exist as a discipline or secret caste. Astronomy was part of a holistic experience of life and environment and sky," he added. "And it also was shaping their societies."

Original article on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works Magazine. Her book "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind Control" will be published in spring 2025 by Johns Hopkins University Press.