23 More Wrecks Found at Greek Hotspot for Sunken Ships

A cluster of Greek islands in the Aegean Sea is giving up some of its deep secrets, as archaeologists have now found 45 shipwrecks there in less than a year's time.

Back in September 2015, a team of Greek and American divers located an astonishing 22 shipwrecks over the course of a 13-day survey around Fourni, which is composed of 13 small islands, some too tiny to show up on maps. The team went back to the eastern Aegean islands in June to expand the search. By the time the three-and-a-half-week survey was finished, the researchers bested their first effort: They documented another 23 shipwrecks, bringing the total to 45.

"Fourni is a constant surprise," said Peter Campbell, co-director of the project from the U.S.-based RPM Nautical Foundation. [See Photos from the Fourni Shipwrecks]

Fortuitous Fourni

The archipelago might be a hotspot for finding shipwrecks today because it was such a popular destination for boats in the past, Campbell told Live Science.

"Fourni is actually a really safe place," Campbell said. "It's just the volume of traffic in every time period that causes the volume of wrecks."

Though Fourni didn't have any major cities in antiquity, it was known as a good anchorage and navigational point for Aegean crossing routes that went both east to west and north to south.

Ships would have anchored in spots that were protected from the usual northwest winds. But once in a while, these vessels could be caught off guard by a big southern storm. If the position of the anchor wasn't changed fast enough, these ships would be in trouble, Campbell noted. Those are the unlucky ships that Campbell and his colleagues have been finding along the coastlines of Fourni.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

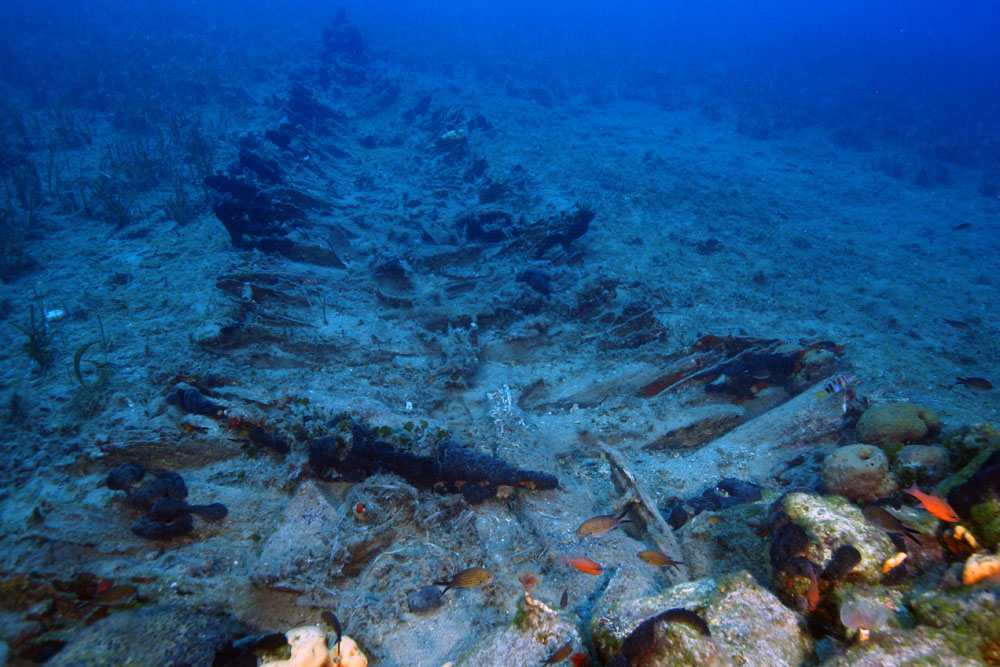

"The ships would just plow into the cliffs and then scatter down," Campbell said. "We find piles of amphoras [ancient Greek vases]. It looks like the scene of a giant car crash, with these ceramics cascading down."

More awaits discovery

The dates of the shipwrecks range from the late Greek Archaic period (525-480 B.C.) to the Early Modern period (A.D. 1750-1850). In addition to the amphoras, which served as the delivery containers of the ancient world, the divers discovered lamps, cooking pots and anchors. In some cases, a wreck's cargo had a clear origin, such as a set of amphoras from the Greek island of Kos dating back to the Hellenistic period (331-323 B.C.).

Campbell and his collaborators from the Greek Ephorate of Underwater Antiquities took representative samples of artifacts from each wreck, but for the most part, they left the underwater objects in place after documenting each site.

Fourni may have one of the world's largest concentrations of ancient shipwrecks. Many of the Mediterranean's larger islands contain only three or four wrecks, the researchers said, and in all of Greece's territorial waters, only about 180 ancient shipwrecks had been well documented (not including the discoveries at Fourni).

There could be more to explore at Fourni, too: The project leaders said they have covered less than half of the archipelago's total coastline in their surveys so far.

The deepest dives of the survey went to 213 feet (65 meters), but Campbell said he thinks there's more to discover below that level, "given how many ships are found in shallow areas and given how steep the cliffs are."

In the next phase of the project, the team hopes to go even deeper with technology such as remotely operated underwater vehicles.

Original article on Live Science.