Powerful earthquakes like the 6.2-magnitude temblor that rocked central Italy early this morning (Aug. 24) are surprisingly common in the region, geologists say.

The shaking was caused by movement in the Tyrrhenian Basin, a seismically active area beneath the Mediterranean Sea. Here, the ground is actually spreading apart, said Julie Dutton, a geophysicist with the U.S. Geological Survey. The same underlying geology was responsible for the devastating 2009 earthquake in the city of L'Aquila, just 34 miles (55 kilometers) away from today’s quake. That earthquake killed more than 300 people.

"It's a pretty complicated or complex area for earthquakes," Dutton told Live Science. "In this area, they have sizable earthquakes that cause destruction every so many years." [Photos of This Millennium's Most Destructive Earthquakes]

Complex damaging geology

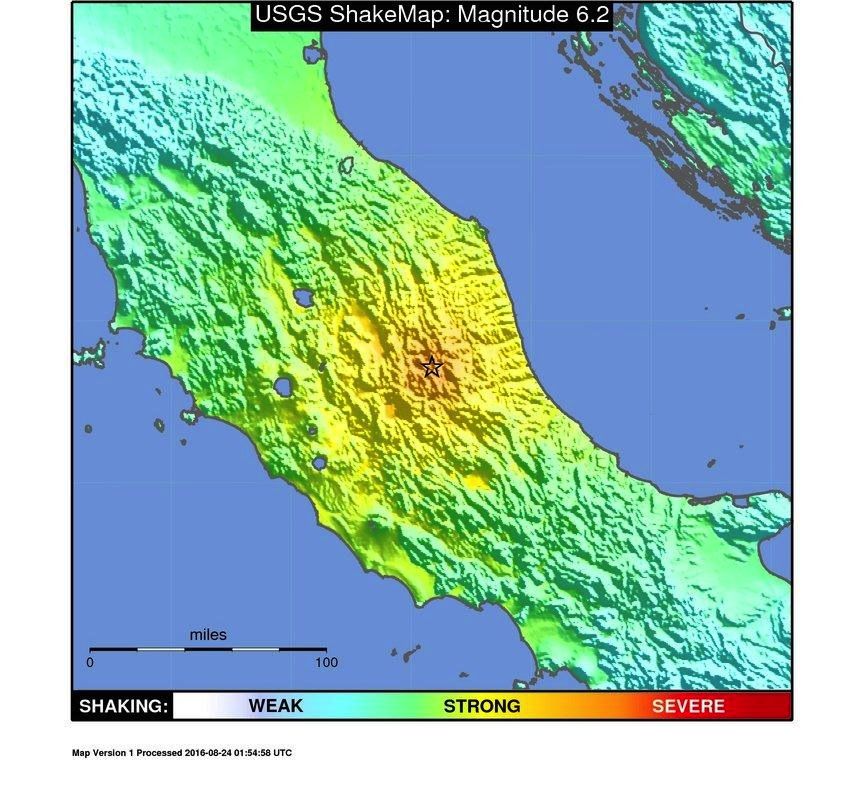

The epicenter of today's quake, which hit around 3:30 a.m. local time, was about 6.2 miles (10 km) southeast of the historic tourist town of Norcia. The earthquake killed at least 73 people and turned scores of charming medieval buildings into rubble. The shaking was felt all the way in Rome, about 70 miles (112 km) southwest of the city.

The temblor was caused by complicated geology. In northeastern Italy, the slow-motion collision of the African and Eurasian plates has pushed up the ground beneath the Alps. In fact, many of the quakes have occurred in towns fringing the Appenine Mountains, along the northeastern coast of Italy.

However, the quakes themselves are not caused directly by this uplift process. Instead, because the continental plate collision zone is drifting southeast, it is stretching the crust beneath a region of the Mediterranean Sea. This ground extension, which occurs at a 90-degree angle relative to the mountain range, is what was behind both the current earthquake and the 2009 L'Aquila temblor, Dutton said.

"It's a normal fault earthquake and it's an expression of the east-west extensional tectonics where the Tyrrhenian Basin is being opened up," Dutton said. Normal faults occur when the ground on one side of the fault slides down relative to the other side, and the motion goes in the direction expected based on the pull of gravity on the Earth, according to the U.S. Geological Survey.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

This region is no stranger to ground shaking. In 2009, the 6.3-magnitude earthquake that struck L'Aquila led to a trial in which the seismologists in the area were convicted of manslaughter for failing to predict the quake. (The guilty verdict against the scientists was later overturned.) In 1997, a 6.0-magnitude earthquake killed more than 100 people and damaged 80,000 homes. And records going back nearly 700 years document terrifying earthquakes in central Italy that caused people to abandon towns during the Middle Ages.

Original article on Live Science.

Tia is the managing editor and was previously a senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.

Most Popular