This Stingray Chews Its Food

Stingrays from the Amazon River chew up their insect meals, just as mammals might, using complex jaw motions to shred the tough outer shells of juvenile beetles and dragonflies, researchers have found.

This finding could shed light on the evolution of chewing, a behavior thought to have helped mammals take advantage of new diets when these animals diversified after the end of the age of dinosaurs, about 65 million years ago.

Stingrays can also now join the elite group of chewers known on the planet. In fact, for a very long time, scientists thought that only mammals practiced chewing. Other animals often just swallow chunks of food, perhaps letting gizzard stones and other gut features grind the meals up. [See Photos of the Insect-Chomping Stingrays]

However, recently scientists have discovered that some other animals, such as carp and spiny-tailed Uromastyx lizards, are arguably practicing chewing in order to eat tough meals such as insects, grasses and even bone, said study lead author Matthew Kolmann, a biomechanist and evolutionary morphologist at the University of Toronto Scarborough.

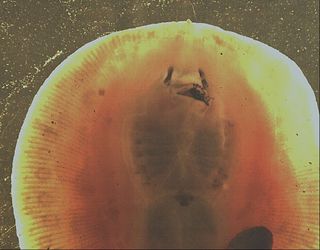

Kolmann said he and his colleagues wondered if insectivorous freshwater stingrays — the only rays and sharks known to dine on insects — might also chew their food. To find out, the researchers used high-speed videography to analyze four specimens of the freshwater stingray Potamotrygon motoro, from the Amazon basin. The scientists recorded the stingrays feeding on a variety of different prey, such as fish and shrimp, as well as dragonfly larvae, while in aquariums. [Video: Watch the Stingrays Chewing Up Insects]

Like mammals that chew, stingrays have loose jaw joints, and can protrude their jaws away from their skulls as well as move their jaws left or right. The scientists discovered that P. motoro used complex jaw motions — effectively chewing — to dismantle prey. Because chewing allowed this species to eat insects, it may have helped P. motoro and its relatives to invade new habitats, the researchers said.

"What I find most interesting is that we have groups of animals that most people would not think have very much in common, freshwater stingrays and mammals, converging on the same solution, chewing, for a common biomaterials problem, eating tough prey like insects," Kolmann said. "This is the sort of evolutionary convergence that has been documented again and again in biology — typically in anatomy, but also in behavior — that illustrates how nature reacts to common challenges in a repeatable, even predictable fashion."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The scientists also found that these stingrays rapidly lift their pectoral fins to suck prey beneath their bodies, where their jaws can then attack the victims. Separating prey-capture behavior from prey-eating behavior may have given this ray and its relatives the opportunity to develop mouths specialized for chewing, Kolmann said.

Freshwater rays could help scientists understand how chewing evolved across the animal kingdom, the researchers said. Kolmann is now using crowdfunding to get the resources to examine the extent that chewing behaviors have spread in other freshwater stingrays.

"I want to examine how these behaviors differ between rays that specialize on insect feeding in contrast to those rays [that] just occasionally eat insects," Kolmann said. "More broadly, within this one family of freshwater rays, the Potamotrygonidae, there are many examples of stingrays [that] have specialized to feed only on some particular kind of prey — crabs, mollusks, insects, even fish — and nothing else. There are plenty of omnivores, too."

The scientists detailed their findings online Sept. 14 in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

Original article on Live Science.

Most Popular