1,700-Year-Old Dead Sea Scroll 'Virtually Unwrapped,' Revealing Text

The En-Gedi scroll, a text that includes part of the Book of Leviticus in the Hebrew Bible that was ravaged by fire about 1,400 years ago, is now readable, thanks to a complex digital analysis called "virtual unwrapping."

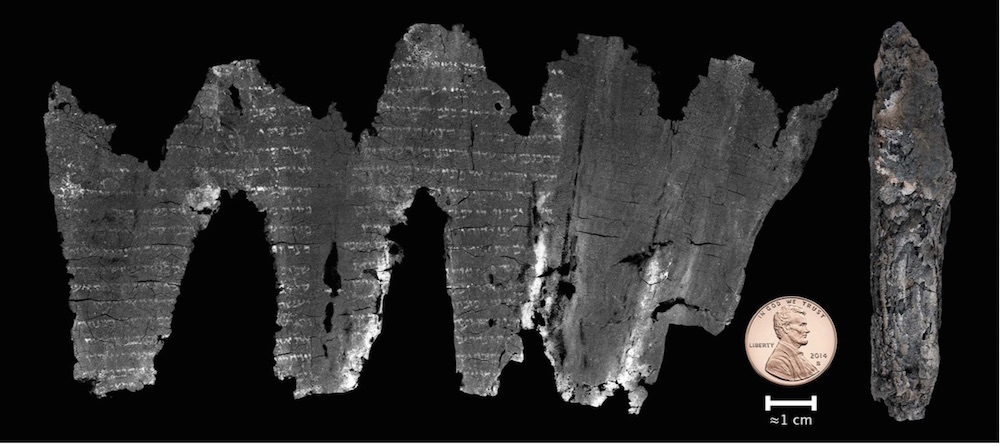

Rather than physically unfurl the scroll, which would have destroyed the crumbling artifact, experts digitally scanned the document, and then virtually flattened the scanned results, allowing scholars to read its ancient text.

"We're reading a real scroll," lead study author Brent Seales, professor and chairman in the department of computer science at the University of Kentucky, said in a news conference yesterday (Sept. 20). "It hasn't been read for millennia. Many thought it was probably impossible to read." [Gallery of Dead Sea Scrolls: A Glimpse of the Past]

Archaeologists found the scroll in 1970 in En-Gedi, where an ancient Jewish community thrived from about the late 700s B.C. until about A.D. 600, when a fire destroyed the site, the researchers said. Excavations of the synagogue's Holy Ark, a chest or cupboard that holds the Torah scrolls, revealed charred scrolls of parchment, or animal skin. But each scroll was "completely burned and crushed, had turned into chunks of charcoal that continued to disintegrate every time they were touched," the researchers wrote in the study.

The En-Gedi scroll is different than the original Dead Sea Scrolls, which a young shepherd discovered in caves near Qumran in the Judean Desert in 1947. However, Dead Sea Scroll has become an umbrella term for many ancient scrolls found in the area, and some researchers also call the En-Gedi artifact a Dead Sea Scroll.

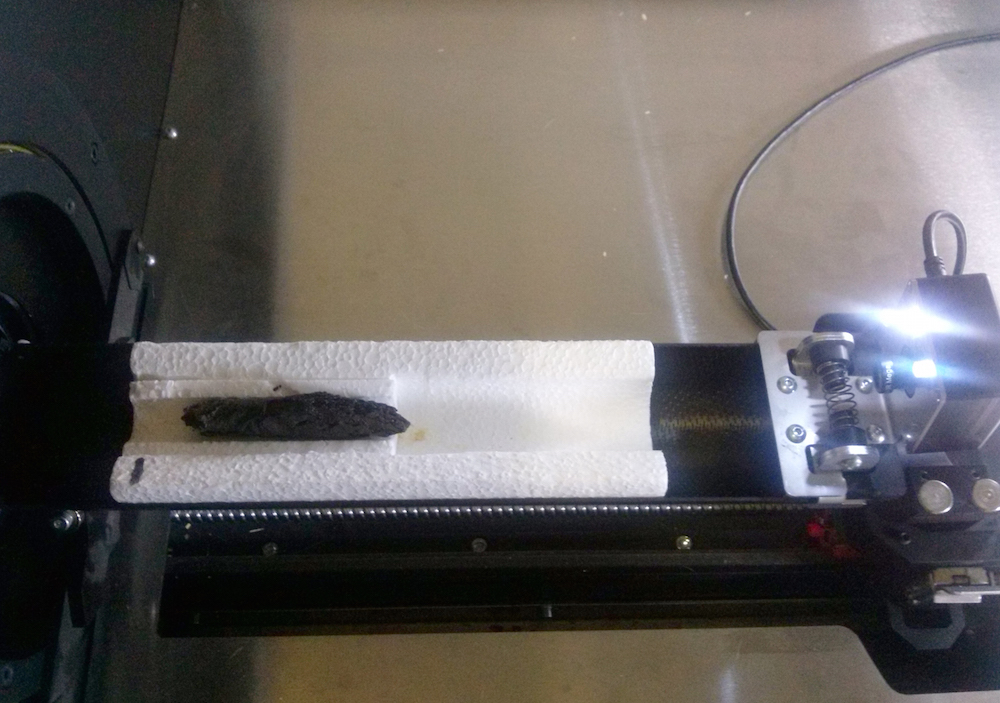

The scorched En-Gedi scroll fragments sat in storage for more than 40 years until experts decided to give them another look, and try the newly developed "virtual unwrapping" method for the first time on the scroll.

Cyber scroll

The virtual journey began in Israel, where experts digitally scanned the rolled-up scroll with X-ray-based micro-computed tomography (micro-CT). At this point, they weren't sure whether the scroll had text within it, said study co-author Pnina Shor, curator and head of the Dead Sea Scrolls Projects at the Israel Antiquities Authority. So, they increased the spatial resolution of the scan, allowing them to capture whether or not each layer had detectable ink.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Their exhaustive attention to detail paid off: There was ink, and it likely contained metal, such as iron or lead, because it showed up on the micro-CT scan as a dense material, the researchers said.

However, the text was illegible. So Shor and her colleagues in Israel sent the digital scans to Seales in Kentucky so he and his team could try the new "virtual unwrapping" technique.

"It was certainly a shot in the dark," Shor said.

Virtual unwrapping

This new method marks the first time that experts have virtually unrolled and noninvasively studied a severely damaged scroll with ink text, Seales said.

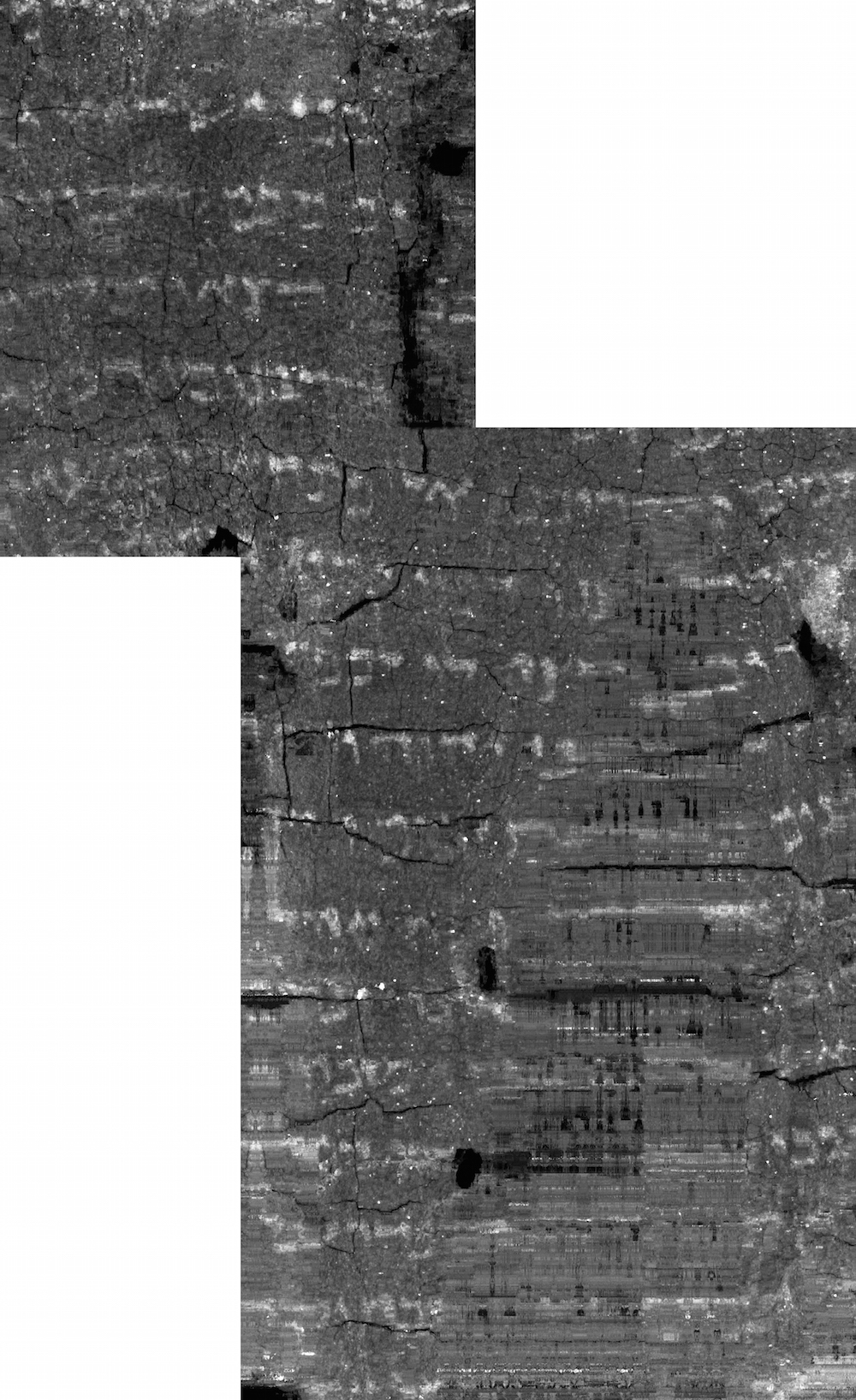

The unwrapping took time and involved three steps: segmentation, texturing and flattening, he said.

With segmentation, they identified each segment, or layer, within the digital scroll, which had five complete revolutions of parchment in the scroll. Then, they created a virtual geometric mesh for each layer made of tiny, digital triangles. They were able to manipulate this mesh, which helped them "texture" the document, or make the text more visible.

"This is where we see letters and words for the first time on the recreated page," the researchers wrote in the study.

Finally, they digitally flattened the scroll, and merged the different layers together into one, flat 2D image that could easily be read. [In Photos: Amazing Ruins of the Ancient World]

Book of Leviticus

The scroll holds the beginning of the Book of Leviticus, the third of the five books of Moses (known as the Pentateuch) that make up the Hebrew Bible, biblical scholars said. In fact, the En-Gedi scroll contains the earliest copy of a Pentateuchal book ever found in a Holy Ark, the researchers said.

The virtual unwrapping revealed two distinct columns of text that include, in total, 35 lines of Hebrew. Each line has 33 to 34 letters. However, there are only consonants, no vowels. This indicates that the text was written before the ninth century A.D., when Hebrew symbols for vowels were invented, said study co-author Emanuel Tov, a professor emeritus in the department of Bible at Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

Radiocarbon dating places the scroll in the third or fourth century A.D., but studies based on historical handwriting place it at either the first or second century A.D., the researchers said. Regardless, the data suggest that it was written within the first few centuries of the Common Era, they said.

These dates make the En-Gedi scroll slightly younger than the original Dead Sea Scrolls, which were written between about 200 B.C. and A.D. 70.

"Hence, the En-Gedi scroll provides an important extension to the evidence of the Dead Sea Scrolls and offers a glimpse into the earliest stages of almost 800 years of near silence in the history of the biblical text," the researchers wrote in the study.

Moreover, the En-Gedi text is "completely identical" to the text and paragraph breaks found in medieval Hebrew Bibles, which are known as the Masoretic text, a text that is still used today. In antiquity until the first century B.C., there were an "endless number of textual forms" of the Masoretic text, earning them the name "proto-Masoretic," Tov said.

But the En-Gedi finding suggests that the standard Masoretic text coalesced relatively early, he said.

"This is quite amazing for us," Tov said. "That in 2,000 years, this text has not changed."

The study was published online today (Sept. 21) in the journal Science Advances.

Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.