Debate 2016: What Goes on in Your Brain When People Invade Your Space

Donald Trump stood very closely behind Hillary Clinton at times during the second presidential debate, held in St. Louis Sunday, prompting some to argue that he was invading her personal space.

While scientists have long known that personal space exists — and that an invasion of personal space can make people feel uncomfortable — it's only recently that scientists have started to understand what's going on in the brain when someone stands too close.

It turns out that it's a very basic function of the brain to maintain a sense of what's going on in the space around you, said Dr. Daphne Holt, an associate professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School in Boston. [10 Things You DIdn't Know About the Brain]

When someone gets too close, there's a very "automatic, instinctual" response in the brain that a person doesn't have much control over, Holt told Live Science. In other words, your response to someone coming into your personal space is not a conscious one.

So what's going on when someone gets too close to you?

In both monkeys and humans, researchers have identified a network of brain regions that includes two areas that respond to objects getting too close: the premotor cortex in the frontal lobe, and the parietal cortex, Holt said.

Very simply put, the premotor area of the brain plays a role in generating movements and motor other actions, and the parietal cortex is a part of the brain that processes sensory information about the world around you, Holt said. In practice, the differences between these two areas' functions aren't quite clear-cut; rather, both areas seem to respond to sensory information and are involved in generating actions, Holt added.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Essentially, the premotor cortex and parietal cortex form a network that recognizes and maintains personal space, Holt said.

In studies in monkeys, researchers have shown that when cells in this network of the brain are stimulated, certain hand movements, such as swatting, and certain facial movements — such as wincing or squinting — occur, Holt said.

Holt has studied how the human brain responds to invasions of personal space. In one study she conducted, published in 2014 in The Journal of Neuroscience, 22 people were shown images of faces, cars and spheres either getting larger (approaching them) or smaller (moving away) while they underwent brain scans. The researchers found that the two areas of the brain responded when faces — but not the cars or the spheres — were "approaching" the subject, but not when they were moving away.

Indeed, the maintenance of personal space, or a zone of defense around the organism, appears to be a very basic survival mechanism, Holt told Live Science. Research has shown that all sorts of animals, from insects to monkeys, have a sense of personal space. [Top 10 Mysteries of the First Humans]

Indeed, this makes sense from an evolutionary perspective, Holt said. Paying close attention to the area of space immediately around a person or animal is important for survival — if something is very close to the body, it might be about to hurt you, so it makes sense that animals devote a good deal of their "neural real estate" to monitoring and protecting that space, Holt said.

What's "personal" about personal space?

While the concept of personal space and protecting it appears to be quite set in the brain, there's still some variation in how people define their own personal space.

The concept of personal space is something people develop over time, from childhood to adolescence to adulthood, Holt said. Once people arrive at adulthood, they tend to have a somewhat set distance that they are comfortable with, Holt said.

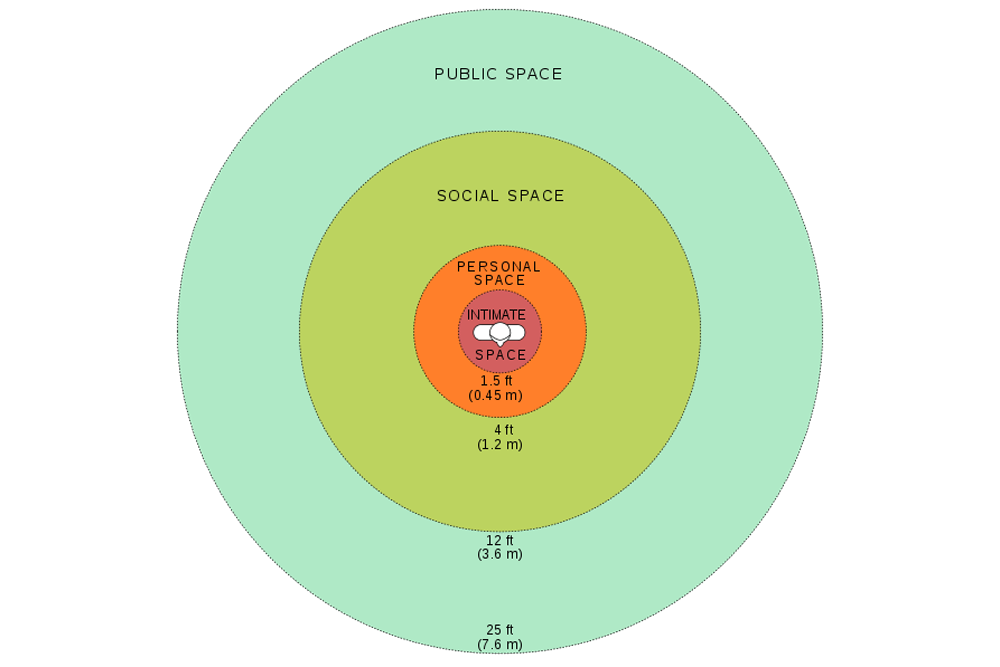

In research from the 1960s, which still stands today, American anthropologist Edward Hall identified four different "bubbles" to describe the space around a person, Holt said. The first bubble is considered "intimate space" and extends, on average, about 18 inches (46 centimeters) from the body; it is generally reserved for family and a person's closest friends. The second bubble, found between 1.5 feet and 4 feet (0.46 to 1.2 m) from the body, is "personal space," which friends and acquaintances may enter. The third bubble, "social space," extends from 4 to 12 feet (1.2 to 3.7 m) from the body, on average, and is where interactions with new acquaintances and strangers can take place. Beyond that is public space, which anyone can enter.

But Holt noted that there are many factors that influence the size and flexibility of personal space, including cultural influences, whether the person standing close to you is the same or opposite gender or of the same social status.

Originally published on Live Science.