This article was originally published at The Conversation. The publication contributed the article to Live Science's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights.

I vividly remember my first haunted house ride – it was at the local fairgrounds, just a temporary carnival truck, more façade than ride. I must have been about seven or eight, and I insisted on bringing along a flashlight. I was quite a fearful child; in this case I hoped the flashlight would break through the darkened illusion and I might sneak a look at the ride's inner workings. I failed miserably: As the ride spun and jolted my flashlight was always a second late. The monsters and spooks jumped out before I could anticipate them; the car hit walls of fake spiders. My light was of little use.

For most of the 20th century, dark rides – as these kinds of rides are called – offered thrills and surprises, and no small dose of fear, to riders bumping along in carts passing through animatronic scenes. But they are rapidly disappearing. In the decade of my professional life I have spent experiencing and documenting these rides around the world, I have seen many great haunted attractions and parks close. Of the thousands of rides created between 1900 and 1970, only 18 still exist.

The closure of Williams Grove, the flooding of Bushkill Park, the sale of Miracle Strip or the destruction of the Spookhouse by Hurricane Sandy have saddened the thousands of fans of these parks. But they have also laid waste to an important record of our popular culture history that should not be left in the dark.

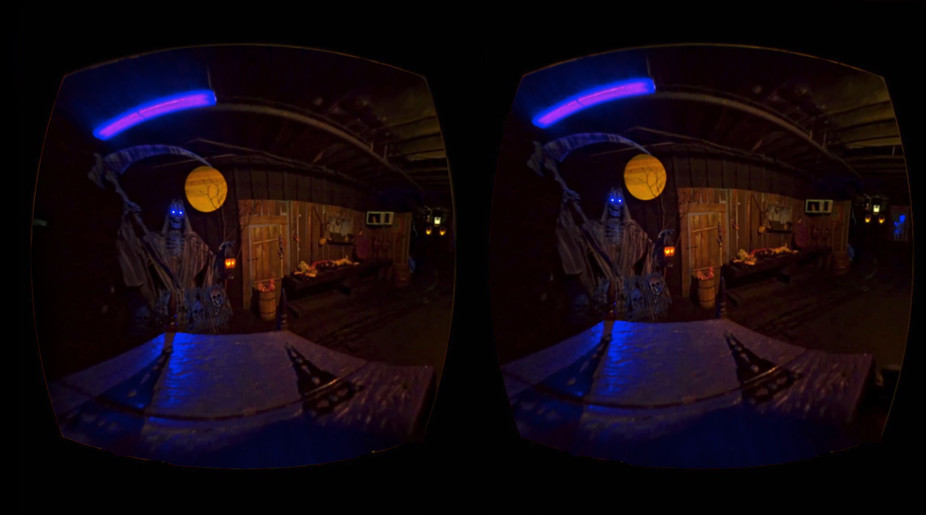

These rides were the virtual reality experiences of their day. Far surpassing cinema, they had sound effects, atmospheric effects and 360-degree immersive space. To preserve them in a way that does these rides justice, my work, the Dark Ride Project, is capturing and archiving the experience of riding the last remaining ghost trains and haunted house rides using today's digital virtual reality technology.

Most recently, we've been visiting the Spook-A-Rama ride at Deno's Wonder Wheel Park in Coney Island, New York. Built in 1955, this classic ride was nearly destroyed by Hurricane Sandy in 2012 and was painstakingly restored by the family that owns the park. On Halloween, we'll release new footage preserving the ride in VR, so it will never be under threat again.

A history of dark rides

The earliest dark rides were the "old mill" rides, which started showing up in the 1900s – there's still one at Kennywood Park in Pittsburgh. Participants floated down a tunnel on log rafts, the way logs used to be transported downriver to mills in the 19th century. The buildings were dark inside, mirroring the real-life mills that lay abandoned across the landscape.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

These floating dark rides sent participants through a series of choreographed vignettes with electric lighting switching automatically on and off as each raft went by. The winding point of view coupled with the sequence of images from either side of the track created a complex narrative and spatial experience. This new way of telling a story involved all of the audience's senses, including the smells of the mechanics, the splashes of water and the touch of hanging props in the dark. In these experiences, viewers would engage intimately with animatronic characters and live actors, looking left and right in surprise.

It was truly an immersive mass medium. Back then, a blockbuster book was more likely to be adapted into a dark ride experience than made into a movie. In 1901, for example, Jules Verne's novel "From The Earth to the Moon" was made into a dark ride for the Buffalo World's Fair – a year before the legendary French cinematic version by George Melies. That ride, which was built by Frederick Thompson, would later go on to tour the country and eventually become the namesake of Coney Island's Luna Park.

In the 1920s, the Depression, the rise of the motor car and the advent of cinema meant that the traditional fairground had a less captive audience. Cities grew but the fairgrounds that were home to these dark rides struggled and began to fall into disrepair. The 1930s saw the rise of the dark ride that we know today, a pragmatic, inexpensive and often ad-hoc form of entertainment. Parks could buy ride carts and build their own sets and scenes. The Pretzel Amusement Ride Company was the most prolific of the time, producing more than 1,400 rides that found homes across America and the world.

The company got its name from the patented ride design that saw the track bend in on itself, like a pretzel. Pretzel rides were cheap to build and maximized the length of the ride – and thereby the experience – given a particular amount of space. The patent drawings show a scripted set of trigger points for sound effects and lighting and could easily be the level maps for a computer game.

Leon Cassidy and Marvin Rempfer started building Pretzel rides in 1928, but even with Cassidy's son making them until the late 1970s, there are now only four left in operation. My documentary journey began at Luna Park's Ghost Train, built by the Pretzel company in 1936, and where I tested the system throughout 2015-16 before taking it on the road.

Planning the preservation

Until now there has been no attempt to make a comprehensive archive of this enormous piece of American popular history. Doing so involves some difficult technical challenges, the solutions to which are evolving as the project goes on. The chief aim is ensuring that there is a clear record of what was in the ride and how it felt.

The Dark Ride Project records a VR experience by sending ultra-low-light cameras on multiple passes of the ride. Then we use computer software to stitch the resulting video into a seamless 360-degree video.

In this way, the rides are captured as they are to be experienced – the footage captures the bumps and shakes of the cart, and doesn't shy away from moments of total darkness.

Unlike my childhood attempt with the flashlight, we don't want to break the illusion, so we use a process called photogrammetry to create complex digital 3D models with the photo data. It allows us to record more about the physical space that lies behind the ride.

We capture these data in conjunction with accelerometer data, which gives us metric information on the speed, direction and location of the cart. This extra information helps build a true academic archive to support the two-dimensional media, recording more about what the ride is doing. The captured jolts and bumps can be recreated using Deakin University's universal motion simulator in conjunction with VR optics.

The result is an experience that is confusing and disorienting but uniquely accurate. It has brought tears to the eyes of nostalgic fans.

So far our work has documented six rides across five parks, from the standalone Haunted House in Oxford, Alabama, to the gravity-propelled classic at Camden Park, West Virginia. Visitors can see previews of all the parks online. We've just raised nearly US$14,000 to digitally preserve the remaining eight rides left in the U.S. – including Coney Island's Spook-A-Rama. We'll need more funding to capture other sites around the world.

Once that is achieved, we hope to expand our work beyond preserving and presenting the dynamic VR content. That includes studying and filming the parks that house these rides, the people who build and maintain them and the communities that love and cherish them.

Joel Zika, Lecturer In Visual Communication Design, Deakin University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus