Fit for a King? Medieval Book 'Illuminates' Likely Theft by Henry VIII

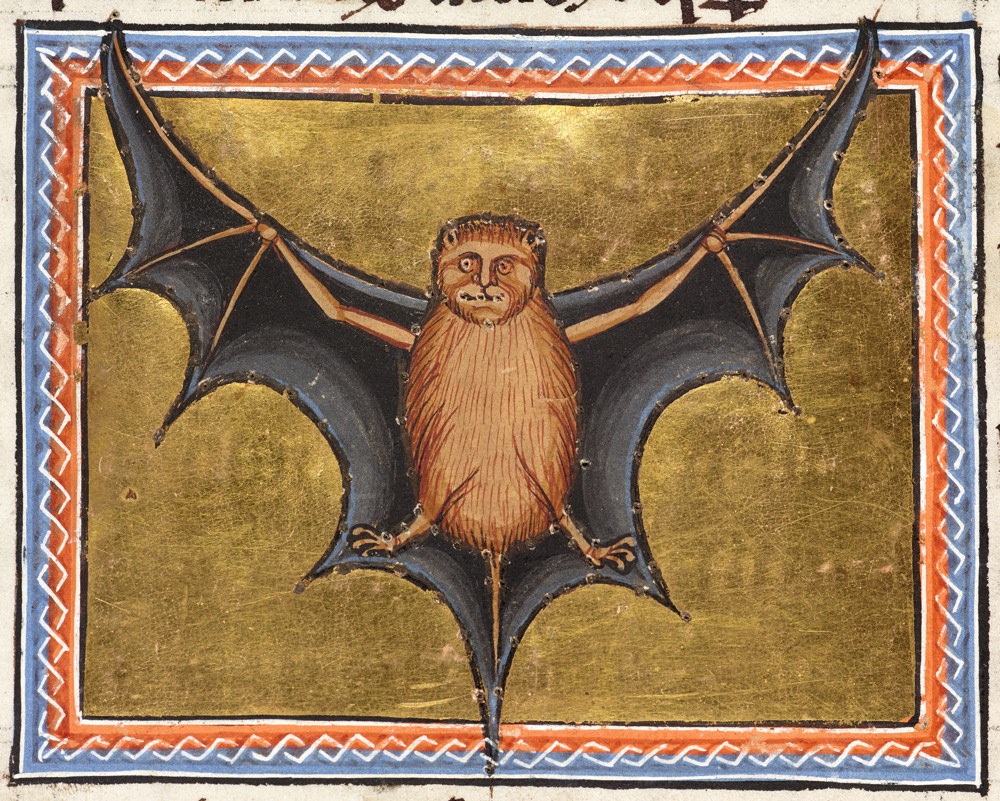

A lavishly illustrated medieval book, full of gold leaf and finely painted images, the "Aberdeen Bestiary" had remained somewhat of a mystery.

Now, with new high-resolution images of each page of the 12th-century manuscript, scientists have found that it was likely seized from a monastic library by scouts of King Henry VIII during the dissolution of monasteries in the 1500s.

As such, the book was likely used as a tool for teaching rather than as a treasure for a royal elite, like one of the king's ancestors, the researchers said. [See Images of the Drawings and Text in the 'Aberdeen Bestiary']

"The book was used for teaching — many words have accents on them to indicate emphasis for reading out loud," lead researcher Jane Geddes, an art historian from the University of Aberdeen, told Live Science. "On one page, there is an area of dirty finger marks at the center top of the page. This would occur if you regularly turned the page upside down to show an audience."

Beastly tales

The book, which is considered an "illuminated" manuscript for its highly decorated pages, particularly those that gleam, or light up, with gold leaf, tells stories about animals as a way to illustrate moral beliefs, according to the University of Aberdeen. It was published in England around the year 1200 and first documented in 1542 in the Royal Library at Westminster Palace, according to the university.

The manuscript was bequeathed to the university's Marischal College in 1625 by Thomas Reid, former college regent and former Latin secretary to King James VI and I. Records suggest that Patrick Young, Reid's friend and son of the king's royal librarian, gave the book to Reid.

Now, Geddes and her colleagues have taken high-resolution digital images of the book and placed them online for the first time, revealing marks that had never been seen before. [Cracking Codices: 10 of the Most Mysterious Ancient Manuscripts]

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"Some were visible to the naked eye, but digitization has revealed many more which had simply looked like imperfections in the parchment," Geddes said.

Tiny holes and notes

She found that many of the book's images had puncture marks around them, likely the result of a copying technique called "pouncing" that is used to transfer an image to another page. "Tiny prick holes are placed around several of the animals," Geddes said. "Blank sheets would be placed under these holes, and charcoal sprinkled over the top, as a simple form of transfer."

The technique generally damages the illustrations and gold leaf on the reverse of the page. "This shows that when it was produced, the need to make copies was more important than keeping the book pristine," she added.

She and her colleagues could also now see production details on the edges of the pages, features that would normally be cut off before the book was finished, Geddes said. These included marks to indicate where to rule the lines, tiny letters to indicate capitalization and notes on the colors to use, she said.

"We also had a closer look at the editing, which took place after the text was finished. There are quite a few corrections to words in the margins," she said, adding that these edits mainly showed up in a section of the book about birds.

That bird section, she said, is copied from another 12th-century book called the "Aviarium," which gives advice to Augustinian canons (an order of men in the Roman Catholic Church) on how to live a good life according to bird lore.

"Why is this section [of the book] so badly copied with many mistakes and omissions? Why is this the section with the special teaching image? I believe this section may provide a clue that the book was destined for a priory of Augustinian canons with novices who needed agreeable training," Geddes said.

Historians had debated whether the book was used by a group of common people or kept in a wealthy private library.

"Although the book ended up in the royal library of Henry VIII, he probably purloined it form a monastery at the Reformation. Its heavy use indicates that it belonged in a working and training establishment, not a rich private library," Geddes said.

A website created to showcase the newly enhanced book pages will allow readers to zoom in on minute details and "examine the precise brush strokes of the artist," Siobhán Convery, head of Special Collections at the university, said in a statement.

Original article on Live Science.

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.