2 Dome-Headed Dinosaurs the Size of German Shepherds Discovered

The discovery of a pair of fossilized skulls from dome-headed dinosaurs is shedding light on how these bizarre creatures called pachycephalosaurs evolved, researchers say.

Both of the skulls are relatively complete. One, discovered in the Kaiparowits Formation of Utah, dates to about 76.5 million years ago. The other, found in the Kirtland Formation of New Mexico, is about 73.5 million years old, the researchers said.

The location of these skulls — in the southern Mountain states — indicates that pachycephalosaurids may have diversified in the south before they moved north and gave rise to the pachycephalosaur known as Stegoceras, said study lead researcher David Evans, an associate professor in the Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology at the University of Toronto. [Dinosaur Detective: Find Out What You Really Know]

Pachycephalosaurids (which means "thick-headed lizards") were bipedal, herbivorous and possibly head-butting dinosaurs that lived during the Cretaceous period (145.5 million to 65.5 million years ago). At that time, a vast seaway divided the eastern part of North America (called Appalachia) from the western part (called Laramidia). Most pachycephalosaurid fossils are found in northern Laramidia, such as modern-day Alberta and Montana, making the two newfound skulls in southern Laramidia rather remarkable discoveries, Evans said.

"There have been some fragmentary specimens that have been found as far south as Texas, but having good quality material and relatively complete skulls has been a true rarity," Evans told Live Science. "The two new specimens really stand out in terms of their completeness, and this allows us to get a much better understanding of their anatomy and their relationships."

Both of the pachycephalosaurids were small — about the size of a German shepherd, but the Utah specimen was about 20 percent larger than the New Mexico one, Evans said.

Bony bumps

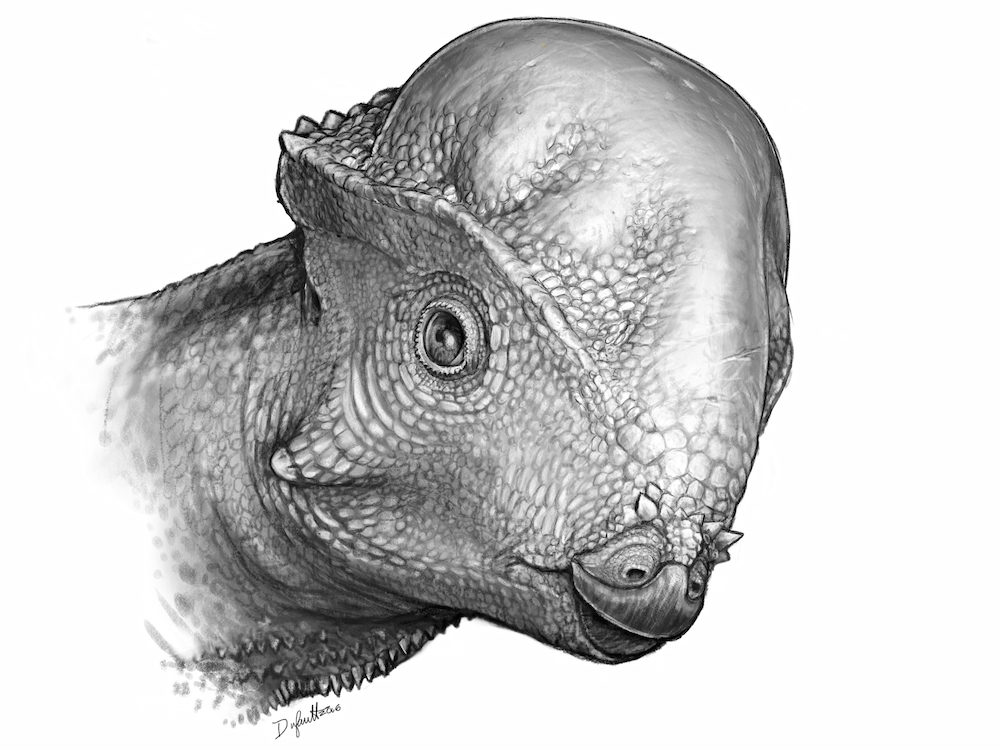

Despite their small differences in size, both had unique bony knobs on the back of the skull, which "is very different from what we've seen in other species before," Evans said. The different boney knobs suggested that they were two new genuses (also called genera) and species, Evans said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The pachycephalosaurids likely used these bony knobs as ornamentation — as a way to distinguish between different species and to woo mates, Evans said. Perhaps these ornaments, much like the pachycephalosaurids' domed heads, grew larger as the creature matured, he said.

Interestingly, a variety of dinosaur groups, including pachycephalosaurids, Tyrannosaurs and Ankylosaurs, moved north around 80 million years ago. It's unclear what caused this northward move, but one idea is that the seaway changed shape, expanding into swaths of land that dinosaurs once inhabited and causing them to leave behind their southern stomping grounds, Evans said.

Perhaps one of the pachycephalosaurid populations in the south moved north, and eventually gave rise to Stegoceras, Evans said. In other words, the two new findings suggest that the "Stegoceras lineage may actually have originated in the southern part of North America, which is unexpected," Evans said. "It tells an interesting story about the evolution of this group that we didn't know before."

The study, which has yet to be published in a peer-reviewed journal, was presented Oct. 27 at the 2016 Society of Vertebrate Paleontology meeting in Salt Lake City.

Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.