How does cannabis get you high?

How do marijuana's psychoactive properties work?

Have you ever looked at your hands? I mean really looked at your hands?

You might think you have, but as the above classic Doonesbury cartoon implies, people who are high on cannabis may perceive mundane objects to be far more fascinating than usual.

How is it that a plant that first emerged on what's now the Tibetan Plateau can change humans' perception of reality? The secret lies in a class of compounds called cannabinoids. While cannabis plants are known to produce at least 140 types of cannabinoids, there's one that's largely responsible for many of the effects of feeling high. It's called tetrahydrocannabinol, or THC.

Related: Why does alcohol make you sleepy, then alert?

When a person smokes or inhales cannabis, THC "goes into your lungs and gets absorbed … into the blood," according to Daniele Piomelli, a professor of anatomy & neurobiology, biological chemistry, and pharmacology at the University of California, Irvine School of Medicine. Edibles take slightly longer trip through the liver, where enzymes transform THC into a different compound that takes a bit longer to have an effect on people's perception of reality.

THC that's inhaled "reaches pretty high levels fairly quickly," Piomelli told Live Science. Within 20 minutes, the circulatory system is carrying molecules of THC to every tissue in the body, including the brain, where it can alter neural chemistry.

"From the lungs, it's a pretty straight shot to the brain," according to Kelly Drew, a professor of chemistry and biochemistry at the University of Alaska Fairbanks.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The THC molecules that pass the blood-brain barrier will find that they fit snugly into receptors that ordinarily receive compounds called endocannabinoids, which the body produces itself. These receptors are part of the endocannabinoid system, which is involved in several functions, including stress, food intake, metabolism and pain, according to Piomelli, who also directs the Center for the Study of Cannabis at UC Irvine.

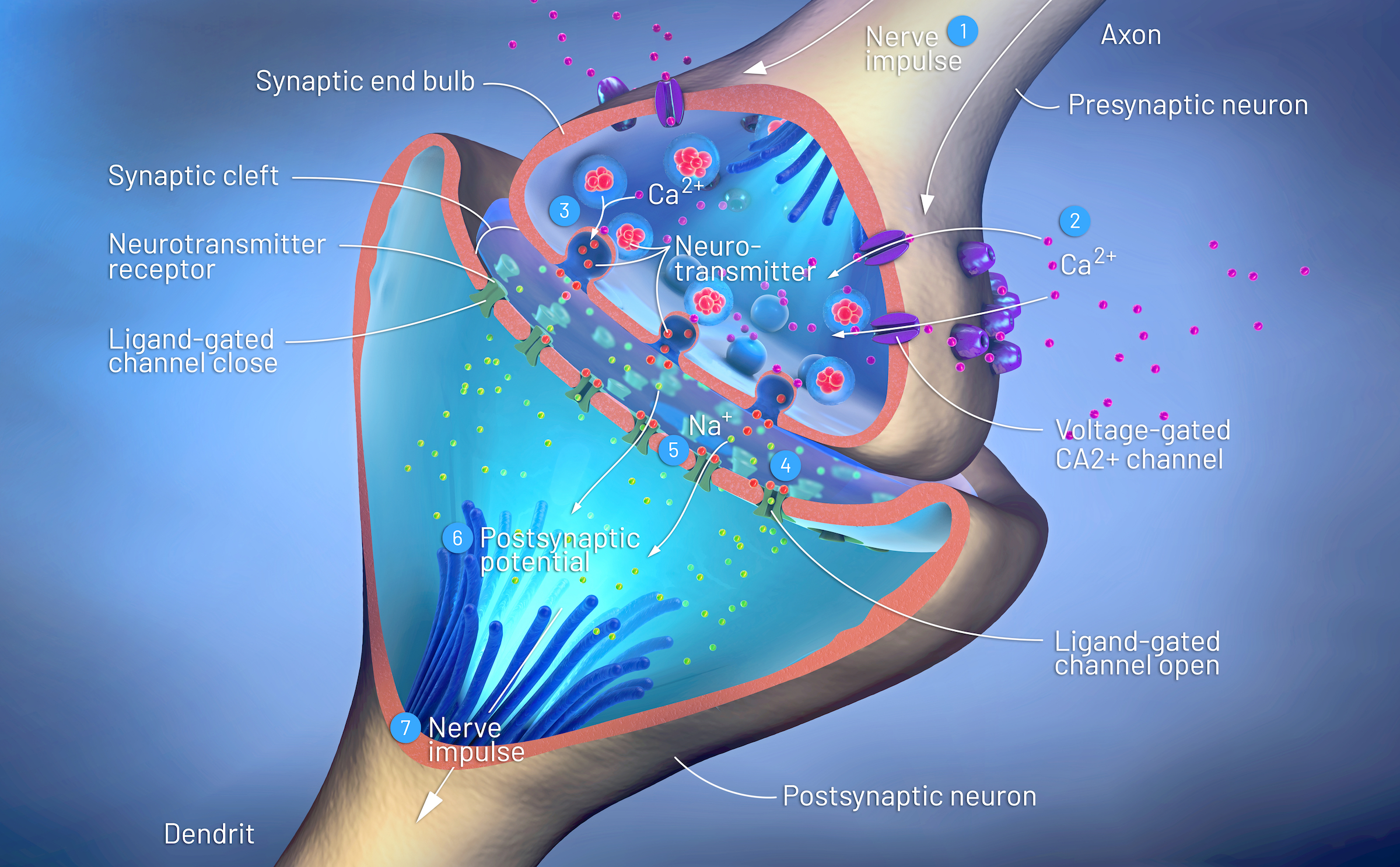

"The endocannabinoid system is the most pervasive, diffused and important modulatory system in the brain because it controls the release of pretty much every neurotransmitter," Piomelli said. Neurotransmitters are molecules that brain cells, or neurons, use to communicate with each other. One neuron sends a message to the next by releasing neurotransmitters, such as dopamine or serotonin, into an infinitesimal gap that separates one neuron from the next. The gap is called the synapse.

The neuron on the receiving end of the synapse is called the postsynaptic neuron, and it "decides whether to fire based on the input it receives," Drew told Live Science. These neural signals cascade through intricate circuits of neural connections that function on a tremendous scale; there are about 85 billion neurons in the brain and as many as 100 trillion connections among them.

The presynaptic neuron sends neurotransmitters across the synapse to the postsynaptic neuron, Piomelli said. But the presynaptic neuron can also receive information. When a postsynaptic neuron has fired, it can send a message across the synapse that says, "the neuron I come from has been activated," stop sending neurotransmitters, Piomelli said. It sends this "stop" message in the form of endocannabinoids that bind to a receptor called cannabinoid 1 (CB1).

Related: What's worse for your brain — alcohol or marijuana?

"Like a sledgehammer"

When THC enters the brain, the molecules diffuse into the synapses where they "activate CB1 receptors," Drew said. THC doesn't cause the most extreme possible response like some synthetic cannabinoids such as K2 or spice, but it does "turn up the volume" and increase the likelihood that the presynaptic neuron it affects will temporarily stop sending neurotransmitters, she said.

"The high is a very simple phenomenon, Piomelli said. "THC comes in like a sledgehammer," flooding the endocannabinoid system with signals the postsynaptic neurons didn't send. When presynaptic neurons across the brain get the memo to stop sending neurotransmitters, this alters the normal flow of information among neurons and results in a high.

Scientists have yet to decipher exactly what happens during this euphoria, however.

That's because, in part, U.S. legal restrictions make it difficult to study cannabis. But from what researchers have gathered so far, THC appears to temporarily "unplug" the default mode network. This is the brain network that allows us to daydream and think about the past and future. When our brains are focused on a specific task, we quiet this network to let our executive function take control.

There's evidence that THC has a significant effect on the network, but researchers aren't quite sure how it happens. There are cannabinoid receptors all over the brain, including in "areas that constitute the key nodes of the [default mode network]," Piomelli said. It could be "that THC deactivates the [default mode network] by combining with those receptors," but it's also possible that THC quiets the network through an "indirect effect that involves cannabinoid receptors in other brain regions."

Scientists are still working to find the mechanisms that result in a person feeling high, but there's some reason to think this effect on the default mode network is a significant piece of the puzzle.

Unplugging the default mode network "takes us into a mental place where the function of the things we experience is less important than the things themselves: our hands are no longer just something we use for touching or grabbing, but something with inner existence and intrinsic value," Piomelli said. Psychedelics, such as LSD or dried psilocybin-containing mushrooms, do the same thing.

However, people can experience highs differently. "The feeling of becoming fascinated by and 'connected' with ordinary things, things we see and use every day, is not universal but does happen, especially when high doses of THC-containing cannabis are used," Piomelli said.

Related: 25 odd facts about marijuana

THC doesn't just affect the default mode network. It may also, in the short-term, flood the brain with dopamine, the brain's reward signal, according to a 2017 study in the journal Nature. (Long-term, it may blunt dopamine's effects, the study found.) That, in part, may explain some of the euphoria associated with a high, and places cannabis in the company of other drugs that people use to feel pleasure.

"Every drug that has rewarding properties affects that system," Drew said.

Aftereffects

The effects of a high from cannabis that's smoked or inhaled typically last for a few hours, though it can take edibles almost that long to start affecting users. And while cannabis isn't the dangerous substance it was made out to be in the 20th century, using it comes with some risk. For one, while cannabis is legal for recreational and medical use in some states, it's still illegal in many parts of the country.

It's also important to bear in mind that cannabis is a potent pharmacological substance. Cannabis can cross the placenta, so pregnant people should avoid it. And "heavy use in the teenage years can be problematic," Piomelli said. For instance, cannabis — and especially synthetic cannabinoids like spice — can exacerbate psychosis. "People who are at risk for that should not smoke it," Drew said.

Finally, cannabis does affect the ability to drive, particularly in occasional users. Drew cautioned that people should not drive for three hours after smoking.

Eventually, the THC will leave the brain; the profusion of blood that brought THC into the brain will carry it to the liver, where it will be destroyed and expelled in urine.

And you're not gonna believe this, but your hands — they were the same the whole time.

Originally published on Live Science.

Grant Currin is a freelance science journalist based in Brooklyn, New York, who writes about Life's Little Mysteries and other topics for Live Science. Grant also writes about science and media for a number of publications, including Wired, Scientific American, National Geographic, the HuffPost and Hakai Magazine, and he is also a contributor to the Discovery podcast Curiosity Daily. Grant received a bachelor's degree in Political Economy from the University of Tennessee.