Turkeys Were Tamed in Mexico 1,500 Years Ago

On Thanksgiving Day, millions of Americans will sit down to enjoy a traditional turkey dinner. Although the U.S. holiday is only a few centuries old, archaeological evidence suggests that in Mexico's central valleys of Oaxaca, turkey was on the menu much earlier — starting at least 1,500 years ago.

In fact, the amount of turkey remains found at a site inhabited by the Zapotec people suggests that turkey meals back then were "second only to dog" in popularity, the researchers wrote in a new study.

The archaeologists described excavating the remains of adult and juvenile turkeys; whole, unhatched eggs; and eggshell fragments from two residential structures dated between A.D. 300 and 1200. The locations and context of the bones and eggshells suggested both domestic and ritual use of the animals, and "multiple lines of evidence" hinted that the breeding and raising of turkeys were commonplace in the region by A.D. 400 to 600, providing the earliest known evidence of turkey domestication, the study authors wrote. [10 Terrific Turkey Facts]

Three subspecies of wild turkey (Meleagris gallopavo) are native to Mexico, and turkey remains were abundant at the site, known as Mitla Fortress. Some remains were found in areas where household trash was buried, but others — both eggs and bones — were uncovered in locations within the residences that were associated with domestic rituals.

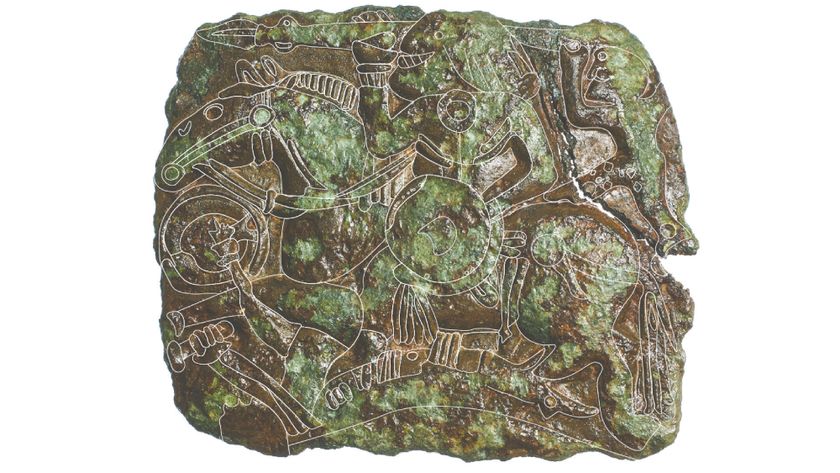

The archaeologists also found three individual turkey skeletons in a grave, likely part of a funeral sacrifice. Two blades made of obsidian were also nearby, and were probably used to slaughter the birds.

According to the archaeological record, turkeys were commonly sacrificed by the Zapotec people for a number of rituals associated with marriage, birth and death, and to provide protection against ill health and poor harvests, the study authors wrote.

The importance of turkeys in Zatopec culture was further demonstrated by evidence of turkey bones integrated into daily life. About one-fourth of the turkey bones the researchers found had been modified to serve as tools, such as awls or textile perforators, or to be worn as jewelry.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Hunted vs. home-grown

Remains from a number of other animals were also discovered around the two structures. The proportion of turkeys was "unusually high," the study authors wrote, suggesting that turkey meat was an important staple in the local diet. However, the researchers also found evidence of turtles, deer, possums, skunks and gophers, as well as an assortment of birds — doves, owls, hawks and quail, to name a few.

But although those animals were hunted, evidence from the site suggests that turkeys were domesticated.

Structures on and inside the turkey bones indicated that both hens (females) and toms (males) were kept, and were likely bred for food, the researchers said. The bones represented a range of ages, from newly hatched chicks and juveniles to fully grown adults. Eggs were similarly plentiful — archaeologists unearthed eight complete eggs, 250 shell fragments representing three partial eggs, and an additional 70 bits of eggshell.

These finds represent the strongest and earliest evidence to date that turkeys were raised in homes in the Oaxaca Valley to be eaten and used in rituals — traditions that are still upheld by the Zapotec people living in Oaxaca today, according to study co-author Gary Feinman, an archaeologist at The Field Museum in Chicago.

"People have made guesses about turkey domestication based on the presence or absence of bones at archaeological sites," Feinman said in a statement. "But now, we are bringing in classes of information that were not available before. We're providing strong evidence to confirm prior hypotheses."

"The fact that we see a full clutch of unhatched turkey eggs, along with other juvenile and adult turkey bones nearby, tells us that these birds were domesticated," Feinman added. "It helps to confirm historical information about the use of turkeys in the area."

The findings were published online yesterday (Nov. 21) in the Journal of Archaeological Sciences: Reports.

Original article on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works Magazine. Her book "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind Control" will be published in spring 2025 by Johns Hopkins University Press.