Mystery Mummy Legs Belonged to Egyptian Queen Nefertari

When Egyptologists broke open the tomb of Queen Nefertari in 1904, they found a once-lavish burial place that had been looted in antiquity. Among the broken objects left behind were three portions of mummified legs.

The legs were assumed to belong to Queen Nefertari, who was one of the royal wives of Ramesses II, or Ramesses the Great. Ramesses II ruled Egypt from around 1279 to 1213 B.C., during Egypt's 19th Dynasty.

But no one had ever scientifically analyzed the mummified legs. Now, new research finds that they belonged to a middle-aged or older woman who stood around 5 feet 5 inches (165 centimeters) tall and may have had a touch of arthritis. The findings suggest that the legs were indeed Nefertari's, researchers reported Nov. 30 in the journal PLOS ONE. [See Images of the Mummified Queen Nefertari]

Revered queen

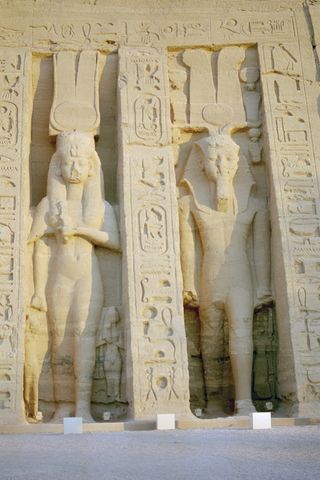

Nefertari is one of ancient Egypt's most famous queens, in part because her tomb was among the most elaborate in the Valley of the Queens near the capital Luxor. The plaster walls were decorated with colorful paintings, and even the ceilings were painted with a likeness of the starry night sky. Nefertari's statue is also found at a rock temple in Abu Simbel in southern Egypt. Her likeness stands side-by-side with her husband's and is the same size, indicating her elevated status. [The 25 Most Mysterious Archaeological Finds on Earth]

The mystery mummy legs, now held at the Egyptian Mueseum in Turin, Italy, are in three fragments, still wrapped in mummy linens. The longest is just over a foot long (30 cm) and consists of part of a femur (thigh bone), the patella (kneecap) and part of the tibia (one of the long bones in the lower leg). The second and third sections consist of a part of a tibia and a part of a femur, respectively.

Rühli and his colleagues X-rayed the leg pieces and found that they almost certainly belonged to a woman. Based on their size and hints of arthritis in the knee, the legs' owner was probably between 40 and 60 when she died. That age is consistent with Nefertari, who is thought to have died in the 25th year of her husband's reign, somewhere between the ages of 40 and 50, the researchers wrote.

The arteries running alongside the tibia showed signs of calcification, possibly due to arteriosclerosis or other age-related hardening of the vessels, the X-rays revealed. A DNA analysis of the sample proved futile because of the degradation and contamination of the DNA molecules. A biochemical analysis, however, found that the substances used in embalming — including the liberal slathering of the bandages in some sort of animal fat — are those used during Egypt's 19th and 20th dynasties, further bolstering the case for Nefertari.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Making the identification

Based on the size of the leg bones, the researchers estimate that the queen would have stood between 5 feet 5 and 5 feet 7 inches (165 to 168 cm), consistent with the size of the sandals found in the tomb, which were a U.S. size 6.5 to 7. Radiocarbon dating put the age of the remains between 1607 and 1450 B.C., earlier than Nefertari's historical life span. She was likely around the same age as her husband, who was born around 1303 B.C. However, the researchers wrote, embalming agents and contamination from sediments might explain the skewed dates.

The researchers made their case for the queen's identity through a process of elimination. There is no sign of a second burial in the tomb, making it unlikely that the remains belong to one of Nefertari's daughters. The early radiocarbon dates make it unlikely that the tomb was reused after Nefertari's time for a newer burial. And though the radiocarbon dates appeared older than they should have been, it's very unlikely that the remains were washed into Nefertari's tomb from some older site, the researchers wrote: Her tomb is uphill from others in the Valley of the Queens.

Though "no absolute certainty exists," they wrote, "the most likely scenario is that the mummified knees truly belong to Queen Nefertari."

Original article on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Most Popular