Feathered Dinosaur Lost Its Tail in Sticky Trap 99 Million Years Ago

About 99 million years ago, an unlucky juvenile dinosaur wandered into a sticky trap and sacrificed a chunk of its tail.

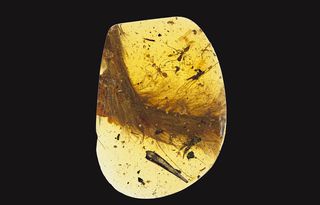

That dinosaur's loss was paleontology's gain. Millions of years later, the truncated tail hangs suspended in a chunk of amber, its feathers and a hint of pigment in preserved soft tissue still visible.

Researchers described the remarkable specimen in a new study, identifying it as the first evidence in amber from a nonavian theropod — a meat-eating and feathered dinosaur that doesn't belong to the lineage that led to modern birds. The remarkable preservation provides a snapshot of dinosaur biology that can't be retrieved from the fossil record, and offers a rare glimpse of feather structures in extinct dinosaurs, which could help scientists better understand how feathers evolved across the dinosaur family tree. [Photos: Amber Trap Nabs Feathered Dinosaur Tail]

A growing body of evidence has emerged in the past two decades indicating the variety of feathers produced by nonavian dinosaurs, but the feathers present an incomplete picture, the study authors wrote. Fossilized feathers are usually compressed and distorted and difficult to reconstruct in 3D. In many cases, they appear in the geologic record without any skeletal fossils nearby, making it impossible for scientists to identify their species.

But amber preserves 3D structures beautifully. The tail fragment described in the study measures about 1.4 inches (36.7 millimeters) and is densely covered with feathers that are reddish brown along the upper surface and paler and finer underneath.

Computed tomography (CT) scans further revealed soft tissues — skin, ligaments and muscles, mostly replaced by carbon. The authors noted that the tail contains at least eight complete vertebrae, and the shape of the bones suggested that this is only a small piece of what was likely a long tail that possibly contained as many as 25 vertebrae, though its overall size suggested that the dinosaur was not fully grown.

And the structure of the tailbones — a string of vertebrae, rather than a fused rod — indicated that the tail's feathery former owner was a nonavian dinosaur, likely a coelurosaur (SEE-luh-ruh-saur), a type of theropod that shared many features with birds.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The fossil feathers have a branching structure that produced both large and small filaments, but they lack a central shaft known as a "rachis," which is an evolutionary feature of modern feathers. This hints that branching in feathers evolved first, the study authors wrote.

This stunning find underscores the unique role that amber plays in helping scientists to interpret what animals may have looked like millions of years ago, and how evolution shaped living animals and their extinct relatives.

"Amber pieces preserve tiny snapshots of ancient ecosystems, but they record microscopic details, three-dimensional arrangements, and labile tissues that are difficult to study in other settings," study co-author Ryan McKellar, a curator of invertebrate paleontology at the Royal Saskatchewan Museum in Canada, said in a statement.

"This is a new source of information that is worth researching with intensity and protecting as a fossil resource," McKellar said.

The findings were published online today (Dec. 8) in the journal Current Biology.

Original article on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works Magazine. Her book "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind Control" will be published in spring 2025 by Johns Hopkins University Press.

Most Popular