Hundreds of Historic Texts Hidden in ISIS-Occupied Monastery

More than 400 texts, dating between the middle ages and modern times, have been saved at the Mar Behnam monastery, a place that the Islamic State group (also known as ISIS, ISIL or Daesh) had occupied for more than two years, until November.

The texts, which were written between the 13th and 20th centuries, were hidden behind a wall that was constructed just a few weeks before ISIS occupied and partly destroyed the Christian monastery, according to Amir Harrak, a professor at the University of Toronto who studied the texts before they were hidden away.

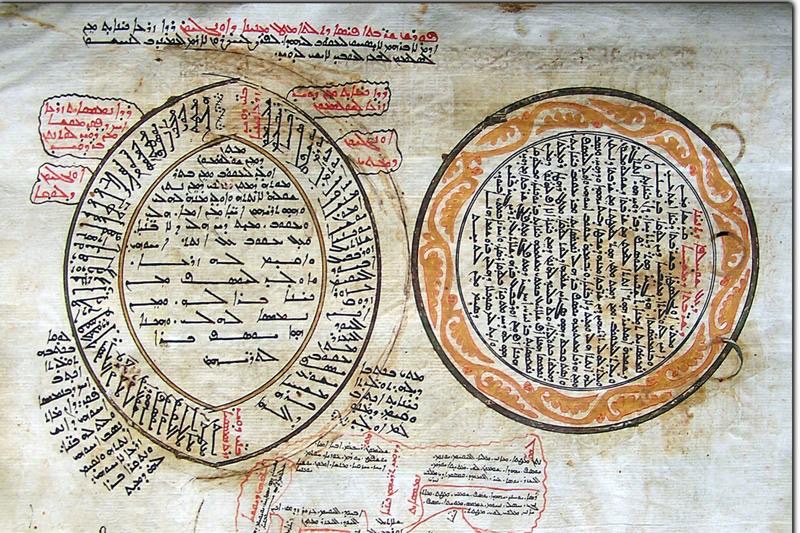

Some of the texts are "beautifully illustrated" by the scribes who copied them, Harrak said. "Each one contains lengthy colophons [notes] written by the scribes, telling historical and social, and religious events of their times — a fact that makes them precious sources," Harrak told Live Science.

The texts are written in a variety of languages, including Syriac (widely used in Iraq in ancient and medieval times), Arabic, Turkish and Neo-Aramaic, said Harrak, who is an expert in Syriac. [See Photos of the Monastery and Saved Historical Texts]

Hidden in an ISIS-occupied monastery

First constructed more than 1,500 years ago, the "Monastery of Martyr Mar Behnam and his sister Sarah" contains texts, carved inscriptions and artwork dating back centuries.

ISIS occupied the monastery from June 2014 to November 2016, when it was recaptured byan Iraqi Christian unit that is working with the government to fight against ISIL. Photos and a news report published by the Agence France-Presse shortly after the monastery was recaptured show that ISIS militants destroyed some of the monastery's buildings (it has multiple buildings), burned what texts they could find, defaced and destroyed the monastery's artwork and inscriptions, and wrote graffiti over the surviving structures.

The texts at Mar Behnam "were hidden in a storage room, 40 days before ISIS invaded the Plain of Nineveh [near Mosul], by a young priest named Yousif Sakat," Harrak said. Sakat "placed them in large metallic cans and built a wall so that no one [would] suspect there is anything, and he succeeded," he added.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Sakat, who was forced to flee the monastery, "kept his undertaking in secret even after the liberation of the Plain, out of fear the manuscripts would be uncovered, until he felt the Plain [was] secure — and he divulged the secret," Harrak said. [See Photos of ISIS Destruction of Iraq Historical Sites]

For more than two years, the texts remained hidden behind the wall. Fortunately, Harrak said, ISIS did not destroy the particular building where the texts were hidden. Reuters reported that ISIS used the surviving buildings at the monastery as a base for its "morality police," who "enforced strict rules against such things as smoking, men shaving their beards and women baring their faces in public."

Future of the texts

The future of the texts is uncertain, and Harrak wonders if the documents should be removed from Iraq, at least for now, for safekeeping.

"What is the future of these manuscripts? Iraq is a restless country," Harrak said. "Should they take them to Europe, for example, or the Vatican Library or somewhere more secure?"

The Iraqi government is unlikely to help protect the texts, Harrak said. TheIraqi government has even ignored Iraq Christian refugees, leaving it to churches to provide relief for these people, he added.

Harrak is a native of Mosul, an Iraqi city near the monastery, which, at the time this story was written, ISIS still partly occupied. (The battle for the city is ongoing.) Harrak left Mosul in 1977 and now lives in Toronto, but he has returned to Iraq often to study ancient texts, inscriptions and artwork.

Original article on Live Science.

Owen Jarus is a regular contributor to Live Science who writes about archaeology and humans' past. He has also written for The Independent (UK), The Canadian Press (CP) and The Associated Press (AP), among others. Owen has a bachelor of arts degree from the University of Toronto and a journalism degree from Ryerson University.