This Brainless Blob Learns — and Teaches, Too

You don't need a brain to learn and teach. New research finds that slime molds, goopy and rather uncharismatic organisms that lack a nervous system, can adapt to a repulsive stimulus and then pass on that adaptation by fusing with one another.

The research suggests that learning may predate the evolution of the nervous system, Toulouse University researchers David Vogel and Audrey Dussutour wrote Dec. 21 in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

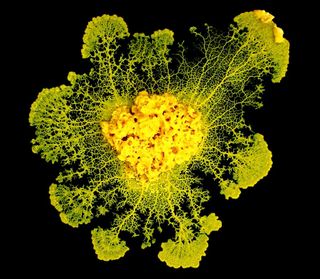

Slime molds are truly bizarre. They're part of the taxonomic group Amoebozoa, which they share with their famous cousins, amoebas. Slime molds can exist as independent cells, but they can also fuse into giant, single-celled organisms with multiple nuclei. The variety studied by Vogel and Dussutour, Physarum polycephalum, is bright yellow and can fuse to form a giant cell that covers hundreds of square centimeters in area. In the wild, P. polycephalum favors habitats like rotting leaves and the moist undersides of logs. [Extreme Life on Earth: 8 Bizarre Creatures]

Slime that learns

Previous studies of slime mold have found that they have a primitive form of memory based on information stored in their trails of goo. Despite being entirely brainless, slime molds can find the fastest route through a maze or between points. P. polycephalum is capable of creeping along at 1.5 inches (4 cm) an hour.

Vogel and Dussutour reported in April 2016 that P. polycephalum can learn. They cultured the slime mold in dishes filled with a mix of agar cell and Quaker Oats and then put the molds next to a patch of food, accessible only by an agar bridge. Half of the time, the researchers coated the bridges with bitter-but-harmless quinine water or caffeine. They found that the slime molds were initially reluctant to cross these bitter bridges, and took twice as long as the slime molds that got to cross bridges free of repellent. Over the course of a few days, though, the slime molds "learned" that the quinine and caffeine were harmless, and sped their passage across the bridges. This demonstrated habituation, or a diminished response to a repeated stimulus.

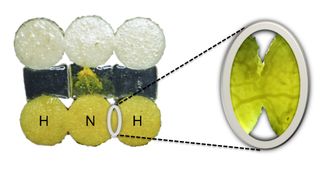

For the current study, the researchers repeated this experiment with another harmless deterrent, sodium chloride — table salt. After confirming that the slime molds responded to the salted bridges first with aversion and then with habituation, Vogel and Dussutour added a twist. After habituation, they exposed slime molds that had experienced the salted bridges to slime molds that had crossed only plain bridges, and allowed those molds to fuse. In the process of fusion, the individual molds kept their nuclei but lost their cell membranes to become one blob-like cell.

Pass it on

After fusion, the researchers timed all of the slime molds as they crossed salted bridges. They found that as long as a single salt-habituated slime mold was in the mix, the new fused molds crossed the salty bridges just as fast as molds that were used to the salt. No matter how many slime molds were fused, the researchers found, just one was enough to habituate the whole gang. [See Amazing Photos of Slime Molds and Other Tiny Wonders]

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The researchers also found evidence that the habituation was the result of some sort of internal transfer of knowledge, not just a diluted mixing of habituated cells with unhabituated cells. For one thing, the tubular extension (called a pseudopod) that first reached the food patch was frequently from the unhabituated portion of the newly fused mega-cell. For another, there was no linear relationship between the amount of habituated mold and the speed of bridge-crossing: One habituated slime mold mixed with three unhabituated slime molds was just as fast as three habituated slime molds mixed with an unhabituated one.

Most strikingly, the lessons persisted after fusion ended. The researchers separated unhabituated and habituated slime molds after one hour and after three hours of union. After 1 hour, the unhabituated slime molds went back to hating salt. But when the researchers waited 3 hours to separate the slimes, the unhabituated slime molds behaved just like habituated slime molds, slithering merrily across the salted bridges. Without brains or even nerve cells, they had "learned" from their habituated brethren.

The research should prompt study into the transfer of adaptive behavioral responses in other types of cells, the researchers concluded.

Original article on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.