Tiny, 540-Million-Year-Old Human Ancestor Didn't Have an Anus

A speck-size creature without an anus is the oldest known prehistoric ancestor of humans, a new study finds.

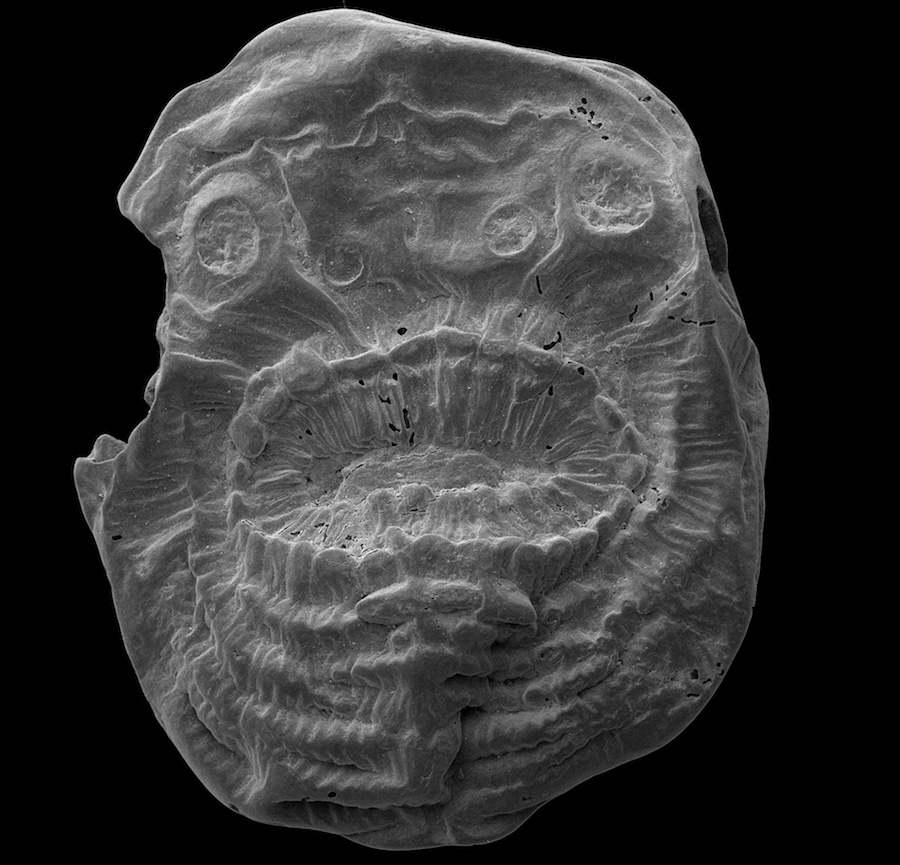

Researchers found the remains of the 540-million-year-old critter — a bag-like sea organism — in central China. The creature is so novel, it has its own family (Saccorhytidae), as well as its own genus and species (Saccorhytus coronaries), named for its wrinkled, sac-like body. ("Saccus" means "sac" in Latin, and "rhytis" means "wrinkle" in Greek.)

S. coronaries, with its oval body and large mouth, is likely a deuterostome, a group that includes all vertebrates, including humans, and some invertebrates, such as starfish. [7 Theories on the Origin of Life]

"We think that as an early deuterostome, this may represent the primitive beginnings of a very diverse range of species, including ourselves," Simon Conway Morris, a professor of evolutionary palaeobiology at the University of Cambridge, said in a statement. "To the naked eye, the fossils we studied look like tiny black grains, but under the microscope the level of detail is jaw-dropping."

At first glance, however, S. coronaries does not appear to have much in common with modern humans. It was about a millimeter (0.04 inches) long, and likely lived between grains of sand on the seafloor during the early Cambrian period.

While the mouth onS. coronaries was large for its teensy body, the creature doesn't appear to have an anus. [See Images of the Bag-Like Animal & Other Cambrian Creatures]

"If that was the case, then any waste material would simply have been taken out back through the mouth, which from our perspective sounds rather unappealing," Conway Morris said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Tiny ancestor

Other deuterostome groups are known from about 510 million to 520 million years ago, a time when they had already started to evolve into vertebrates, as well as sea squirts, echinoderms (starfish and sea urchins) and hemichordates (a group that includes acorn worms).

However, these incredibly diverse animals made it hard for scientists to figure out what the common deuterostome ancestor would have looked like, the researchers said.

The newfound microfossils answered that question, they said. The researchers used an electron microscope and a computed tomography (CT) scan to construct an image of S. coronaries.

"We had to process enormous volumes of limestone — about 3 tonnes [3 tons] — to get to the fossils, but a steady stream of new finds allowed us to tackle some key questions: Was this a very early echinoderm or something even more primitive?" study co-researcher Jian Han, a paleontologist at Northwest University in China, said in the statement. "The latter now seems to be the correct answer."

The analysis indicated that S. coronaries had a bilaterally symmetrical body, a characteristic it passed down to its descendants, including humans. It was also covered with a thin, flexible skin, suggesting it had muscles of some kind that could perhaps help it wriggle around in the water and engulf food with its large mouth, the researchers said.

Small, conical structures encircling its mouth may have allowed water it swallowed to escape from its body. Perhaps these structures were the precursor of gill slits, the researchers said.

Molecular clock

Now that researchers know that deuterostomes existed 540 million years ago, they can try to match the timing to estimates from biomolecular data, known as the "molecular clock."

Theoretically, researchers can determine when two species diverged by quantifying the genetic differences between them. If two groups are distantly related, for instance, they should have extremely different genomes, the researchers said.

However, there are few fossils from S. coronaries' time, making it difficult to match the molecular clocks of other animals to this one, the researchers said. This may be because animals before deuterostomes were simply too miniscule to leave fossils behind, they said.

The findings were published online today (Jan. 30) in the journal Nature.

In another paper, researchers reported on the discovery of another type of tiny animal fossil from the late Cambrian. These creatures, called loriciferans, measured about 0.01 inches (0.3 mm) and, like S. coronaries, lived between grains of sand, the researchers said in a study published online today in the journal Nature Ecology and Evolution.

The newly identified species, Eolorica deadwoodensis, discovered in western Canada, shows when multicellular animals began living in areas once inhabited by single-celled organisms, the researchers said.

Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.