Cancer-Fighting Army? Magnetic Robot Swarms Could Combat Disease

Magnetically controlled swarms of microscopic robots might one day help fight cancer inside the body, new research suggests.

Over the past decade, scientists have shown they can manipulate magnetic forces to guide medical devices within the human body, as these fields can apply forces to remotely control objects. For instance, prior work used magnetic fields to maneuver a catheter inside the heart and steer video capsules in the gut.

Previous research also used magnetic fields to simultaneously control swarms of tiny magnets. In principle, these objects could work together on large problems such as fighting cancers. However, individually guiding members of a team of microscopic devices so that each moves in its own direction and at its own speed remains a challenge. This is because identical magnetic items under the control of the same magnetic field usually behave identically to each other. [The 6 Strangest Robots Ever Created]

Now, scientists have developed a way to magnetically control each member of a swarm of magnetic devices to perform specific, unique tasks, researchers in the new study said.

"Our method may enable complex manipulations inside the human body," said study lead author Jürgen Rahmer, a physicist at Philips Innovative Technologies in Hamburg, Germany.

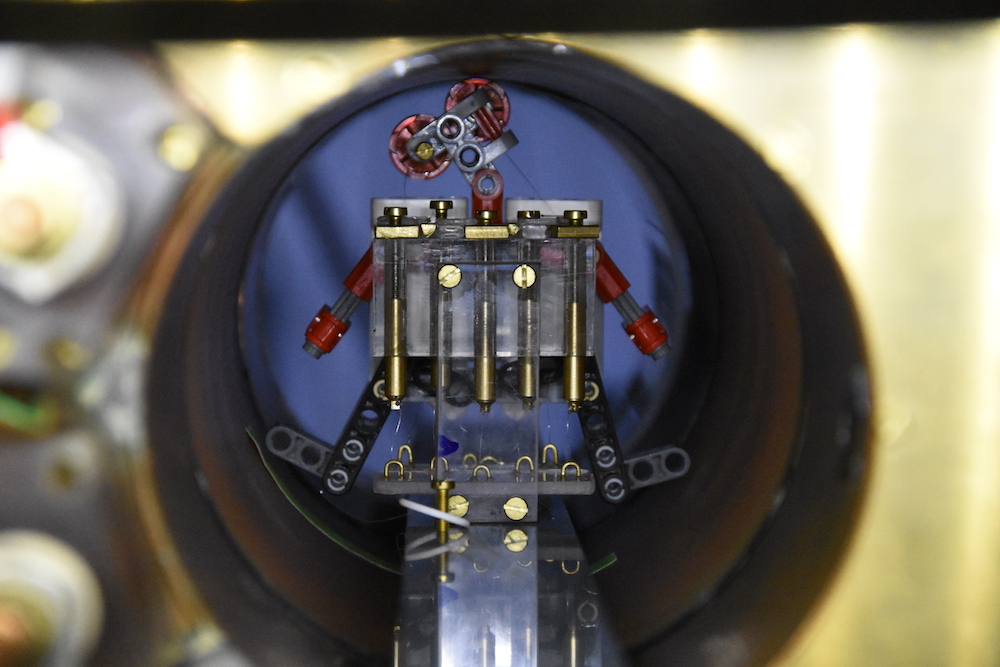

First, the scientists created a number of tiny identical magnetic screws. The researchers next used a strong, uniform magnetic field to freeze groups of these magnetic screws in place. In small, weak spots within this powerful magnetic field, the microscopic screws are free to move. Superimposing a relatively weak rotating magnetic field could make these free screws spin, the researchers said.

In experiments, the researchers could make several magnetic screws whirl in different directions at the same time with pinpoint accuracy. In principle, the scientists noted, they could manipulate hundreds of microscopic robots at once.First, the scientists created a number of tiny identical magnetic screws. The researchers next used a strong, uniform magnetic field to freeze groups of these magnetic screws in place. In small, weak spots within this powerful magnetic field, the microscopic screws are free to move. Superimposing a relatively weak rotating magnetic field could make these free screws spin, the researchers said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"One could think of screw-driven mechanisms that perform tasks inside the human body without the need for batteries or motors," Rahmer told Live Science.

One application for these magnetic swarms could involve magnetic screws embedded within injectable microscopic pills. Doctors could use magnetic fields to make certain screws spin to open the pills, the researchers said. This could help doctors make sure that cancer-killing radioactive "seeds" within the pills target and damage only tumors rather than healthy tissues, cutting down on harmful side effects, the researchers said. Once the pills deliver a therapeutic dose of radiation, physicians could then use magnets to essentially switch the pills off. (The pills would be made of metallic material that would otherwise keep radiation from leaking out.)

Another potential application could be medical implants that change over time, the researchers said. For instance, as people heal, magnetic fields could help alter the shape of implants to better adjust to the bodies of patients, Rahmer said.

In the future, researchers could develop compact and magnetic field applicators to control tiny magnetic robots, and use imaging technologies such as X-ray machines or ultrasound scanners to show where those devices are located in the body, Rahmer suggested.

The scientists detailed their findings online Feb. 15 in the journal Science Robotics.

Original article on Live Science.