Tully the Spineless Monster? Experts Say Ancient Beast Had No Backbone

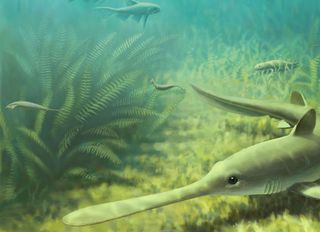

The Tully monster, a bizarre beast that plied the seas 307 million years ago, has long mystified scientists. Its features, including eyes like a hammerhead's and a pincer-like mouth, look like they belong on Dr. Seuss creatures, and have made it difficult for scientists to classify it. But last year, two different scientific groups did just that, independently announcing that the ancient animal was likely a marine vertebrate.

However, those two groups got it wrong, according to a new paper published online Monday (Feb. 20) in the journal Paleontology.

Rather, the Tully monster (Tullimonstrum gregarium) was likely an invertebrate — a spineless beast, researchers said in the new study. [Photos: Ancient Tully Monster's Identity Revealed]

"This animal doesn't fit easy classification because it's so weird," study lead researcher Lauren Sallan, an assistant professor in the Department of Earth and Environmental Science at the University of Pennsylvania, said in a statement. "It has these eyes that are on stalks, and it has this pincer at the end of a long proboscis, and there's even disagreement about which way is up. But the last thing that the Tully monster could be is a fish."

Mysterious monstrosity

The sea monster has mystified scientists for nearly 60 years. Amateur fossil collector Francis Tully discovered the first specimen in Illinois in 1958, and scientists have found thousands more since then. The species attracted so much public interest that it became the state fossil of Illinois, and murals of the creature still decorate the sides of U-Haul trucks.

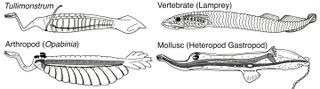

However, no one could clearly define the monster: Some called it a worm; others classified it as a shell-less snail. And there was even a push to call it an arthropod, a group that includes lobsters, spiders and insects, Sallan said.

In the first study of the creature, published in March 2016 in the journal Nature, researchers looked at more than 1,200 Tully monster fossils. They reported seeing a light band going down the creature's midline. This band was likely a notochord, a type of primitive backbone, they said. Moreover, the fossils had remains of internal organs, such as gill sacs, that were characteristic of vertebrates, and teeth that looked like those of a lamprey, a jawless fish, they said. [Image Gallery: Ancient Monsters of the Sea]

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

However, these descriptions are off base, Sallan and her colleagues said. The faint circles that are interpreted as gill slits sit on septa (thin walls or cavities) rather than gill tissues or pouches, suggesting that they weren't involved in breathing, Sallan and her colleagues wrote in the study. In addition, "a dark circle under the 'gills' was interpreted as the liver, despite the liver's universal placement in vertebrates' posterior to [behind] the pharynx," the researchers wrote in the study.

"In the marine rocks, you just see soft tissues; you don't see much internal structure preserved," Sallan said.

Eye analysis

In the other study, published in April 2016 in the journal Nature, scientists used a scanning electron microscope to show that the monster's eyes held melanosomes — structures that produce and store melanin. These complex tissues indicated that the creature was likely a vertebrate, the researchers of that study said.

But animals that aren't vertebrates, including arthropods and cephalopods, such as the octopus, also have complex eyes, Sallan and her colleagues noted. [Photos: The Freakiest-Looking Fish]

"Eyes have evolved dozens of times," Sallan said. "It's not too much of a leap to imagine Tully monsters could have evolved an eye that resembled a vertebrate eye."

The new analysis showed that the creature had a cup eye — in essence, a simple structure that doesn't have a lens, she said. "So the problem is, if it does have cup eyes, then it can't be a vertebrate, because all vertebrates either have more complex eyes than that or they secondarily lost them," Sallan said. "But lots of other things have cup eyes, like primitive chordates, mollusks and certain types of worms."

Of the more than 1,200 Tully monster specimens analyzed, none appeared to have structures seen in aquatic vertebrates, notably otic capsules — structures in the ear that help animals with balance — and a lateral line, which is a sensory structure that helps fish orient their bodies, according to the researchers of the new study.

"You would expect at least a handful of the specimens to have preserved these structures," Sallan said. "Not only does this creature have things that should not be preserved in vertebrates; it doesn't have things that absolutely should be preserved."

"Dog's breakfast"

Other scientists who have studied the monster said they are glad that the new study is drawing attention from the scientific world back to Tully.

"It is important to remember that this is how science works," said James Lamsdell, an assistant professor of paleobiology at West Virginia University, who also co-authored the March 2016 study calling the Tully monster a vertebrate. "It is natural for new ideas, based off new information, to be questioned by the scientific community. This back-and-forth drives research, and further studies will continue to test the position of the Tully monster among the vertebrates."

However, the authors of the new study "do not present any new information, nor do they restudy the specimens," Lamsdell told Live Science in an email. "As such, no convincing alternatives are presented for where this strange animal fits on the tree of life."

That idea was seconded by Jakob Vinther, a senior lecturer of macroevolution at the University of Bristol in the United Kingdom, who co-wrote the April 2016 study, and called the new study "a bit of a dog's breakfast" (in other words, a mess).

"They don't evaluate the implications for the evolution of [arthropods or mollusks]," Vinther wrote in an email to Live Science. "I have worked on both arthropods and mollusks, and they don't fit comfortably in there by any means. So they essentially pushed the problem aside [of where Tully fits]."

However, the new study makes some good points, Vinther said. [Image Gallery: 25 Amazing Ancient Beasts]

"I agree, actually, with the fact that some of the interpretations to put them [the Tully monsters] deep inside vertebrates is wrong, but they fit very well in the stem lineage [the group leading up to the vertebrates]," he said. "In fact, vertebrates [are] the only place that an animal with such eyes could fit."

Whatever Tully is, it's important to give the monster its proper due, Sallan said.

"Having this kind of misassignment really affects our understanding of vertebrate evolution and vertebrate diversity at this given time," Sallan said. "It makes it harder to get at how things are changing in response to an ecosystem if you have this outlier. And though, of course, there are outliers in the fossil record — there are plenty of weird things, and that's great — if you're going to make extraordinary claims, you need extraordinary evidence."

Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.