US-Sized Dust Storms Seen on Mars

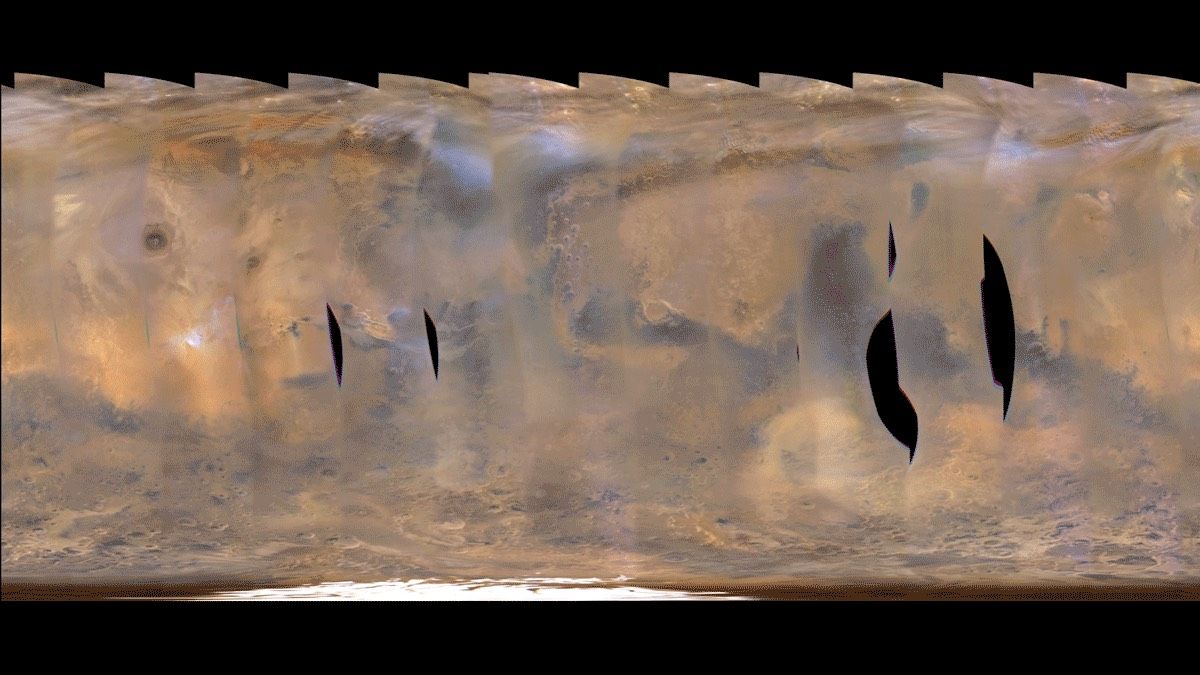

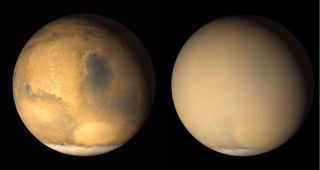

Last week, scientists were surprised to see a second regional dust storm on Mars blooming only two weeks after another one in the same storm track.

NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) showed both storms generated in the Acidalia area of northern Mars, then moving to the southern hemisphere and expanding to sizes bigger than the United States. While the path is normal, the frequency of the storms is unexpected.

"What we're trying to understand is the weather of Mars," said Richard Zurek, chief scientist for the Mars program at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory and the project scientist for MRO.

One mystery is what determines the scale of a dust storm. There are many local storms, a few that become more regional, and then even fewer where enough dust is lofted into the atmosphere to become global, Zurek said.

So far, scientists see that global dust storms tend to happen during the spring and summer in the southern hemisphere, when Mars is closest to the sun and heating is at a maximum to generate winds. The orbit tends to change every 100,000 years. So in older times, when Mars' elliptical orbit exposed other parts of the planet to maximum heating, dust generation may have happened differently — but scientists don't know that for sure yet, Zurek pointed out.

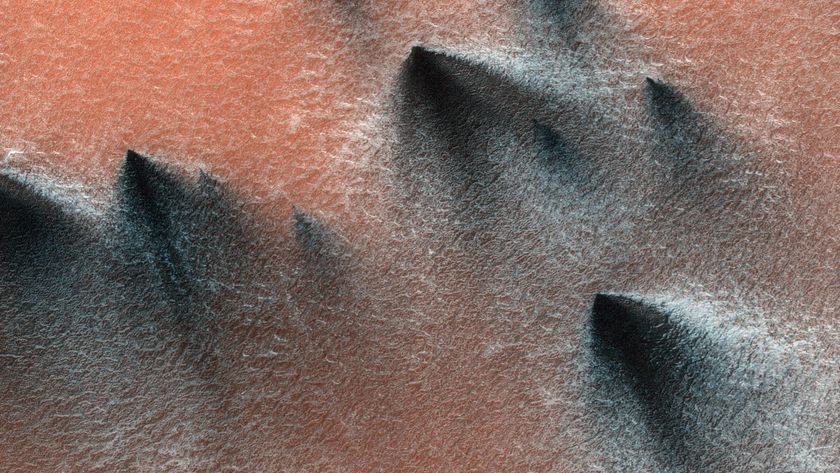

Only the smallest dust particles are lifted high in the atmosphere; sometimes, larger bits of dust hop along the surface and dislodge finer materials that float up. Global dust storms have happened a few times since NASA started observing Mars. One famous example was a 1971 dust storm that raged as Mariner 9 orbited the planet. Scientists saw the peaks of volcanoes peeking above the clouds, but not much else. The last global dust storm was 2007.

While Martian dust dominates the lower atmosphere, dust from other sources, like the planet's moons Phobos and Deimos, is sprinkled in the upper part. A new model based on NASA's Mars Atmosphere and Volatile Evolution Mission (MAVEN) spacecraft suggests that most dust is from interplanetary sources.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"It has been found that flux rate at Mars is dominated (~2 orders of magnitude higher) by interplanetary particles in comparison with the satellite originated dust," say Jayesh Pabari and P.J. Bhalodi in an article published in the journal Icarus.

"It is inferred that the dust at high altitudes of Mars could be interplanetary in nature," they continue, "and our expectation is in agreement with the MAVEN observation."

Zurek said scientists are monitoring the infall of dust into Mars' atmosphere, and saw a spike when Comet Siding Spring zoomed close to the planet in October 2014, shortly after MAVEN arrived. The spacecraft detected a particular kind of dust — magnesium — that was ionized as it fell into the atmosphere, generating auroras.

At upper altitudes, however, dust does not have much effect on the climate, Zurek said. Occasionally particles will seed clouds, but that's about it. Zurek added that the effects could have been different in the ancient past, when there were more asteroids jumbled around the solar system and thus more dust was falling into Mars.

Some recent media reports discussing the paper suggested that a dust ring may be forming around Mars, but Zurek said there's no evidence of a substantial ring happening — or even a tenuous one, like what is around Jupiter.

"We haven't been able to find it yet, but we keep looking," he said with a chuckle.

Originally published on Seeker.

Elizabeth Howell was staff reporter at Space.com between 2022 and 2024 and a regular contributor to Live Science and Space.com between 2012 and 2022. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, speaking several times with the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.

Most Popular