No Lips! T. Rex Didn't Pucker Up, New Tyrannosaur Shows

The fearsome Tyrannosaurus rex didn't have lips if it looked anything like a newly discovered tyrannosaur species that scientists are calling the "frightful lizard."

The fearsome Tyrannosaurus rex didn't have lips if it looked anything like a newly discovered tyrannosaur species that scientists are calling the "frightful lizard."

Some paleontologists have suggested that T. rex and its meat-eating dinosaur brethren had lips, although that research has yet to be published in a peer-reviewed journal. The new study challenges the idea of a pouty-mouthed ancient beast, suggesting that tyrannosaur faces were covered with sensitive scales, much like the faces of modern alligators.

"There's no evidence for lips here," said study lead researcher Thomas Carr, a vertebrate paleontologist and an associate professor of biology at Carthage College in Wisconsin. "The flat scales cover the entire side of the snout and go to the tooth row," leaving no room for lips, he said. [See Images of the Newfound 'Frightful Lizard']

Paleontologist Vickie Clouse, now an instructor of paleontology at Montana State University–Northern, discovered the first specimen of the newfound dinosaur in Montana's Two Medicine Formation in 1989, and other paleontologists, including study co-author David Varricchio of Montana State University, uncovered more individuals in the following decades.

The team named the 75-million-year-old tyrannosaur Daspletosaurus horneri; its genus name (Daspletosaurus) means "frightful lizard," and its species name (horneri) honors Jack Horner, a paleontologist who led some of the excavations of the new specimen at the Two Medicine Formation and an adviser to the "Jurassic Park" franchise.

"I'm truly honored," Horner told Live Science in an email. "It is particularly cool for me that it's a new species of tyrannosaur, since tyrannosaurs have long been the subject of many of my research projects."

D. horneri would have been a sight to behold during its lifetime: It measured almost 30 feet (9 meters) long, about three-fourths the size of T. rex, and stood 7.2 feet (2.2 m) tall at its hip bone (its highest point as tyrannosaurs did not stand up straight). It had a wide snout and, just like other tyrannosaurs, three sets of horns on its face.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Its sharp teeth — some measuring up to 2.7 inches (7 centimeters) long — helped it hunt horned dinosaurs, crested duck-billed dinosaurs, dome-headed pachycephalosaurs and smaller theropods (the group of meat-eating dinosaurs that includes the Velociraptor and D. horneri), the researchers said.

No lips

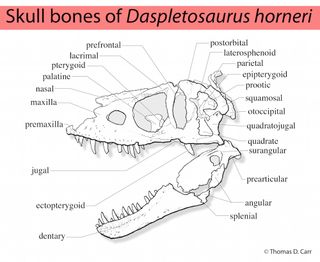

The researchers studied the D. horneri skulls in minute detail, and then compared them with the skulls of crocodilians (a group that includes crocodiles and their semiaquatic reptile relatives, such as alligators and caimans), birds and mammals, as scientists have determined what skin type goes with each bone texture in these creatures.

"Based on the similarities of the facial nerves and arteries we found in those same groups, which left a trace on the bone, we were able to then reconstruct … the new tyrannosaur species," study co-author Jayc Sedlmayr, an evolutionary biologist at the Louisiana State University School of Medicine in New Orleans, said in a statement.

The comparisons revealed that many of the tyrannosaur's skull features are identical to those of crocodilians — the bones in their snouts and jaws are rough, with the exception of a narrow band of smooth bone along the tooth row, Carr said. And this band leaves no space for lips, he said.

In crocodilians, flat scales cover the rough jaw and snout bones, Carr said. Given that tyrannosaurs had the same bone texture, it's likely that they had the same covering, he said. Likewise, other anatomical clues suggest that these scales were likely as sensitive in the tyrannosaurs as they are in crocodilians, and would have helped D. horneri capture prey, interact with mates and sense the world around them. [Gory Guts: Photos of a T. Rex Autopsy]

This discovery "is maybe the coolest part of the study," said Steve Brusatte, a paleontologist at the University of Edinburgh in Scotland, who was not involved with the study. "It conjures up a really terrifying image: a bus-sized tyrannosaur with a face covered in gnarly scales, sniffing you out with its nose and then sensing your movements with its skin receptors on its snout."

The lipless finding is "a reasonable conclusion," said Thomas Holtz, a vertebrate paleontologist at the University of Maryland, who was not involved in the study.

"The issue of dinosaur lips has been confusing for some time," Holtz told Live Science in an email. "[But] in tyrannosaurs, particularly the big specialized ones, the roughened, slightly inflated surface of the bones along the edges of the jaw does not resemble the quality of bone in lipped lizards. It does indeed more closely resemble the condition in lipless crocodilians."

Family relation

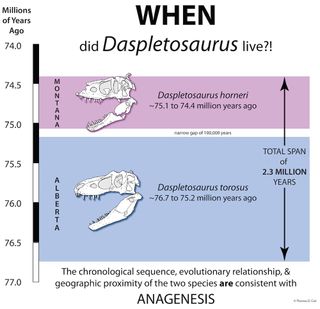

After carefully examining D. horneri's anatomy, the researchers concluded that the species is likely the descendant of another tyrannosaur in the same genus: Daspletosaurus torosus.

D. torosus lived in what is now Alberta, Canada, just north of where researchers found D. horneri in Montana. But D. torosus lived during an earlier period, from about 76.7 million to 75.2 million years ago. In contrast, D. horneri lived from about 75.1 million to 74.4 million years ago, a period that fits into the "direct descendant" hypothesis, the researchers said.

"Finding this type of potential ancestor-descendant lineage in dinosaurs is very rare, because usually, the fossil record is too poor to be sure," Brusatte said. "It's not a slam-dunk case, but I think the authors have made a good argument."

But Holtz said he was on the fence about the possible relation, mostly because "our sampling is insufficient to demonstrate this," he said.

The findings were published online today (March 30) in the journal Scientific Reports.

Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Most Popular