Scientists Can Now Create Glass Figurines with a 3D Printer

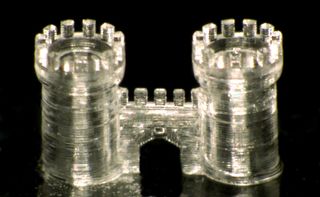

Intricate glass creations such as miniature castles and tiny pretzels can now be fabricated using 3D printing, according to a new study. The technique could one day be used to manufacture lenses for smartphone cameras as well as other key glass components, researchers said.

Archaeological research suggests humans have employed glassmaking for millennia. The process typically requires hot furnaces and harsh chemicals. Recently, scientists have investigated whether they could sidestep these drawbacks using 3D printing.

A 3D printer is a machine that creates items from a wide variety of materials: plastic, ceramic, metal and even more unusual ingredients, such as living cells. These devices work by depositing layers of material, just as ordinary printers lay down ink, except 3D printers can also deposit flat layers on top of each other to build objects in three dimensions. [The 10 Weirdest Things Created by 3D Printing]

Until now, the only methods for shaping glass using 3D printing also required using a laser or heating the materials to searing temperatures of about 1,800 degrees Fahrenheit (1,000 degrees Celsius), the researchers in the new study said. In both cases, the end products were coarse, rough structures that were not suitable for many applications, the researchers added.

"People thought glass was too difficult to work with via 3D printing," said study senior author Bastian Rapp, a mechanical engineer at the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology in Eggenstein-Leopoldshafen, Germany

Now, scientists have developed a new technique to fabricate complex glass structures using a standard 3D printer. The secret, the researchers said, is something they call "liquid glass."

"What this work does is it closes an important gap in the palette of modern 3D printing," Rapp told Live Science.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The scientists began with particles made of silica, the same material used to make glass. These particles were only 40 nanometers, or billionths of a meter, wide, which is about 2,500 times thinner than the average strand of human hair.

These silica nanoparticles were dispersed in an acrylic solution. The researchers could then use a standard 3D printer to fabricate complex items using this "liquid glass," the study said. Ultraviolet light could harden these objects into a kind of plastic similar to acrylic glass.

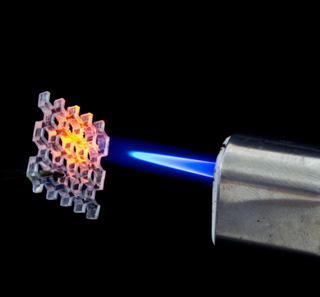

When these pieces of plastic were exposed to temperatures of about 2,370 degrees F (1,300 degrees C), the plastic burned away while the silica nanoparticles fused together into smooth, transparent glass structures, the study said. With the aid of additives, this technique can print colored glasses, tinted green, blue or red, for example, the researchers said.

"Glass is one of the oldest materials that mankind has used, and it's still a high-performance material, and for many applications, the only choice of material," Rapp said. "What our research does is bridge a necessary gap between 21st-century manufacturing techniques and a material that's centuries old."

The commercial 3D printer the researchers used could print features as tiny as a few dozen microns. For comparison, the average human hair is 100 microns wide.

This new method does not require harsh chemicals, and it produces glass components smooth and clear enough for use as lenses and in other applications, the researchers said.

"You can think of creating tiny lenses for smartphone cameras," Rapp said. "You can think about creating chemically and thermally resistant micro reactors made from glass that chemical reactions can take place in."

This new technique could also help create optical and photonics components for high-speed data transmission, Rapp said. (Photonic devices manipulate light just as electronic circuits manipulate electricity.) "You can also think much bigger, with 3D curved pieces of glass for architecture," Rapp said.

"We are now spinning off a company to commercialize this technology," Rapp said. "We hope that in a few years' time, glass will be as convenient to 3D print as plastic is nowadays."

The scientists detailed their findings online April 19 in the journal Nature.

Original article on Live Science.