Mount Etna's Slide into the Sea Could Trigger a Catastrophic Collapse

Gravity is pulling Mount Etna toward the sea, raising the possibility that the flank of the active volcano may someday suffer a catastrophic collapse.

There is no indication that such a collapse is imminent, but new research finds that the Italian volcano's southeastern flank is moving both above ground and under the sea. These movements mean that the risk of a slope collapse is higher than previously believed, researchers reported today (Oct. 10) in the journal Science Advances.

"We need to understand better how this transition works and what sort of triggers does it take for a collapse," study co-author Morelia Urlaub, a researcher in marine geodynamics at the GEOMAR Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research in Kiel, Germany, told Live Science. [History's Most Destructive Volcanoes]

Eruptive Etna

Mount Etna is Europe's most restless volcano. This mountain has experienced active periods since at least around 6000 B.C. and is currently in an eruptive cycle that has been ongoing since September 2013, according to the Smithsonian Institution's Global Volcanism Program.

Researchers using satellite data and GPS measurements have also observed that Mount Etna's southeastern flank has been creeping seaward for at least 30 years. In March, scientists from The Open University in the United Kingdom reported that the slope moved an average of about a half-inch (14 millimeters) each year between 2001 and 2012 alone.

The debate, Urlaub said, has been whether this creep results from magma moving beneath and within the volcano or whether it results mostly from gravity. Mount Etna is constantly spewing material onto its slopes, she said, and gravity pulls that new material downward.

"That's common with these big volcanoes," Urlaub said. "They spread at the base."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Mount Etna also has its "feet in the water," Urlaub said. Its slopes continue below the Sicilian coast and into the Mediterranean. Until now, though, no one had measured how the flank was moving below sea level.

Submarine slipping

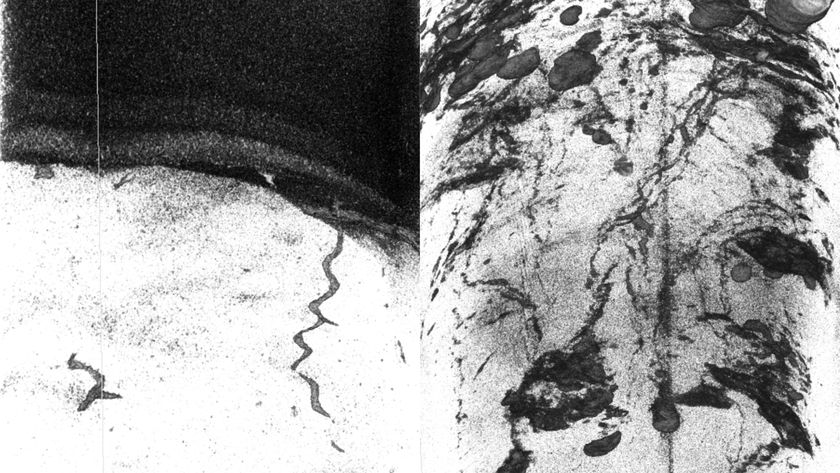

Using a network of seafloor sensors, Urlaub and her team measured how sound traveled from transponder to transponder every 90 minutes between April 2016 and July 2017. The time it took sound to travel reveals the distance between transponders, so the researchers could detect any changes in the seafloor over the study period.

They found that during an eight-day period in May 2017, a fault on the mountain's submarine flank shifted as much as 1.6 inches (4 centimeters). This was not an earthquake; the movement happened without a fault rupture or seismic waves, but rather as a gradual slip.

The area where the researchers measured the slip is far from the magma chambers at the center of Etna, Urlaub said. That means that the movement did not result from magma rising within the volcano's subterranean chambers; instead, it's the inexorable work of gravity, which pulls on the entire slope above and below the water.

That's bad news for Etna's risk to human life, Urlaub said.

"We know from other volcanoes in the geological record that these have collapsed catastrophically and caused really, really big, fast landslides," she said, "and if these landslides enter the sea, they can cause a tsunami."

The chance of that happening at Etna can't yet be quantified, Urlaub said. Scientific observations of the mountain date back only a few decades, she said, and the whole history of Etna spans 500,000 years. More monitoring is needed to detect whether there are any changes in how the slope is moving and to estimate its risk of collapse, she said.

"There is a hazard," Urlaub said. "We just have to keep an eye on Etna's flank and how it is moving."

Originally published on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Most Popular