Bone-Crushing Wolves Once Roamed Alaska

Bone-crushing wolves that specialized in hunting giant prey once roamed the icy expanses of Alaska, an international team of researchers now finds.

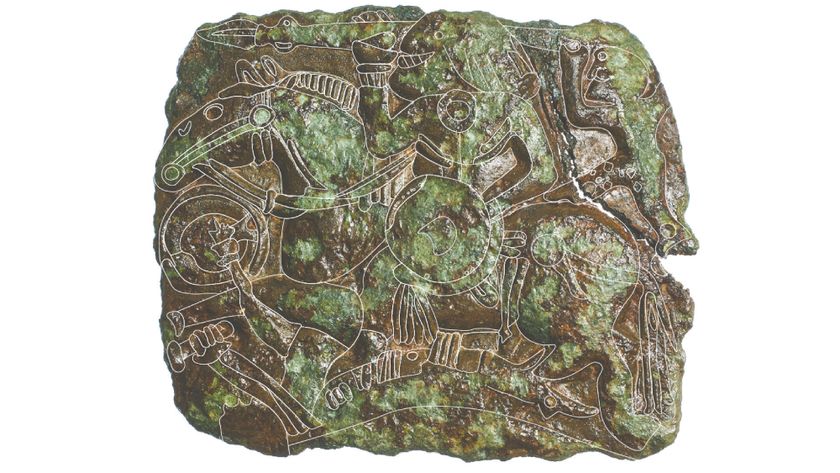

The scientists unexpectedly discovered what apparently was a novel subspecies of gray wolf (Canis lupus) as they analyzed genes from skeletal remains that had sat in museum collections for up to a few decades after excavation from Alaskan permafrost deposits. The ancient DNA, which dated back 12,500 to 40,000 years, did not match any modern wolves, and closer investigation of the bones uncovered remarkable differences.

These extinct predators had strong jaws and massive teeth, ideal for killing and devouring mammoths and other megafauna.

"Studies of their tooth wear and fracture rate showed high levels of both, consistent with regular and frequent bone-cracking and -crunching behavior," UCLA vertebrate paleontologist Blaire Van Valkenburgh said.

These ancient carnivores, with broad skulls and short snouts, faced stiff competition from some very formidable rivals, including lions, short-faced bears and saber-toothed cats.

"The density of these large predators was likely much greater than any we see today, even than in Africa," Van Valkenburgh told LiveScience. "There's good reason for that—we don't want them to eat us, our children or our pets."

The intense struggle over prey the wolves at times faced made their bone-crushing jaws potential lifesavers, helping them consume what victims they caught more fully and make the most of meals. The findings are detailed online June 21 in the journal Current Biology.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

These wolves lived during the Pleistocene epoch, back when an up-to-1,000-mile-long land bridge joined Alaska with Siberia. At the end of the last Ice Age, the ice caps melted and drowned that isthmus under what is now the Bering Strait. As their megafauna prey declined in numbers because of a combination of climate change and over-hunting by humans, the wolves died off.

"You had this form of gray wolf specialized for taking large prey, and this fits into a pattern you often see of specialists going extinct, as they can have greater difficulty adapting to changing environments than more generalized species do," Van Valkenburgh said. "With global warming coming fast, we might lose a number of specialized forms of species for the same reason."

Vertebrate paleoecologist Russell Graham at Pennsylvania State University said these findings "are very, very cool" and suggested researchers go back and look closer at skeletal remains of other animals from the Pleistocene. "It wouldn't surprise me if it turned out there were a lot of extinct forms of animals to be discovered," he said.

For instance, the tapir—a somewhat pig-like beast related to horses and rhinoceroses—is now thought of as mostly a tropical animal, but fossils of tapirs are found as far north as St. Louis and central Pennsylvania during glacial periods 16,000 to 20,000 years ago. "There is a modern tapir that lives in the Andes that can tolerate freezing temperatures, and this extinct species of tapir was probably very similar to the Andean one," Graham said.