Ancient Spider Guts Revealed in 3-D

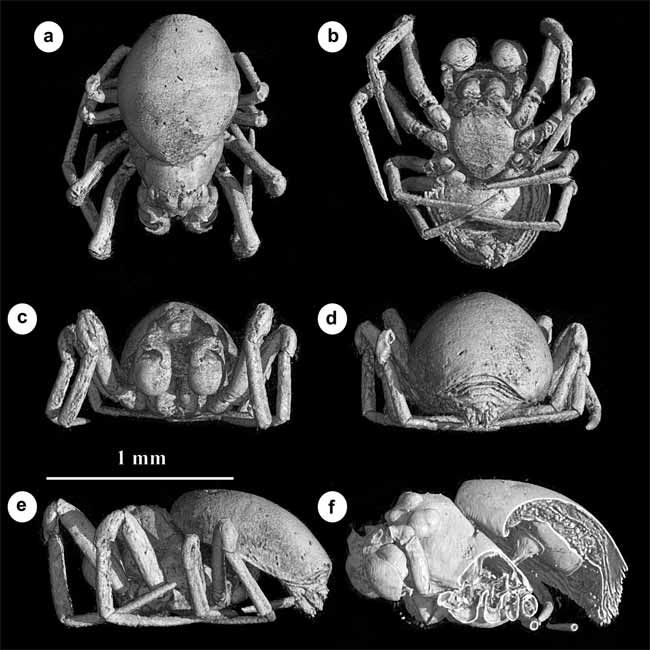

Digital wizardry has allowed scientists to see the insides of a 53-million-year-old fossilized spider in 3-D.

The male spider is about the size of a pinhead (or a stack of three salt grains) and lived during the early Eocene epoch, from about 55 million to nearly 34 million years ago.

It represents a new genus and species dubbed Cenotextricella simoni. It's also the earliest fossil species of a family of micro-spiders called Micropholcommatids from Australia, New Guinea, New Caledonia, New Zealand and Chile.

The fossil was found preserved in amber in the Paris Basin in France.

“Amber provides a unique window into past forest ecosystems," said lead author David Penney, a paleo-arachnologist at the University of Manchester in England. "It retains an incredible amount of information, not just about the spiders themselves, but also about the environment in which they lived."

Normally, observing the minute features of an already tiny specimen would mean cracking into the amber, potentially destroying the sample.

Instead of physical dissection, Penney and his colleagues used Very High Resolution X-ray Computed Tomography to scan the bug through its amber grave.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The resulting 3-D reconstructions could be sectioned and viewed from various angles, essentially allowing for digital dissection of the spider specimen.

“This technique essentially generates full 3-D reconstructions of minute fossils and permits digital dissection of the specimen to reveal the preservation of internal organs," Penney said.

- Video: Mating Spiders

- Vote: The Ugliest Animals

- Image Gallery: Creepy Spiders

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.