Double Trouble: What Really Killed the Dinosaurs

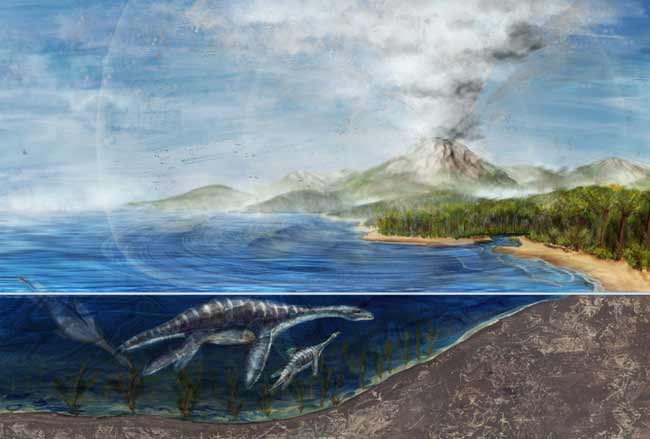

Instead of being driven to extinction by death from above, dinosaurs might have ultimately been doomed by death from below in the form of monumental volcanic eruptions. The suggestion is based on new research that is part of a growing body of evidence indicating a space rock alone did not wipe out the giant reptiles. The Age of Dinosaurs ended roughly 65 million years ago with the K-T or Cretaceous-Tertiary extinction event, which killed off all dinosaurs save those that became birds, as well as roughly half of all species on the planet, including pterosaurs. The prime suspect in this ancient murder mystery is an asteroid or comet impact, which left a vast crater at Chicxulub on the coast of Mexico. Another leading culprit is a series of colossal volcanic eruptions that occurred between 63 million to 67 million years ago. These created the gigantic Deccan Traps lava beds in India, whose original extent may have covered as much as 580,000 square miles (1.5 million square kilometers), or more than twice the area of Texas. Arguments over which disaster killed the dinosaurs often revolve around when each happened and whether extinctions followed. Previous work had only narrowed the timing of the Deccan eruptions to within 300,000 to 500,000 years of the extinction event. Now research suggests the mass extinction happened at or just after the biggest phase of the Deccan eruptions, which spewed 80 percent of the lava found at the Deccan Traps. "It's the first time we can directly link the main phase of the Deccan Traps to the mass extinction," said Princeton University paleontologist Gerta Keller. Clues in other life forms Keller and colleagues focused on marine fossils excavated at quarries at Rajahmundry, India, near the Bay of Bengal, about 600 miles (1,000 kilometers) southeast of the center of the Deccan Traps near Mumbai. Specifically, they looked at the remains of microscopic shell-forming organisms known as foraminifera. "Before the mass extinction, most of the foraminifera species were comparatively large, very flamboyant, very specialized, very ornate, with many chambers," Keller explained. These foraminifera were roughly 200 to 350 microns large, or a fifth to a third of a millimeter long. These showy foraminifera were very specialized for particular ecological niches. "When the environment changed, as it did around K-T, that prompted their extinction," she added. "The foraminifera that followed were extremely tiny, one-twentieth the size of the species before, with absolutely no ornamentation, just a few chambers." As such, these puny foraminifera serve as very distinct tags of when the K-T extinction event started. The researchers found these simple foraminifera seem to have popped up right after the main phase of the Deccan volcanism. This in turn hints these eruptions came immediately before the mass extinction, and might have caused it. Double trouble Both an impact from space and volcanic eruptions would have injected vast clouds of dust and other emissions into the sky, dramatically altering global climate and triggering die-offs. Keller's collaborator, volcanologist Vincent Courtillot at the Institute of Geophysics in Paris, noted upcoming work from her collaborators suggests the Deccan eruptions could have quickly released 10 times more climate-altering emissions than the nearly simultaneous Chicxulub impact. Keller stressed these findings do not deny that an impact occurred around the K-T boundary, and noted that one or possibly several impacts may have had a hand in the mass extinction. "The dinosaurs might have faced an unfortunate coincidence of a one-two punch—of Deccan volcanism and then a hit from space," she explained. "We just show the Deccan eruptions might have had a significant impact—no pun intended." Although paleontologist Kirk Johnson at the Denver Museum of Nature and Science called these new findings "significant," he noted a great deal of evidence connected a single massive impact with the K-T extinction event. He suggested that advances in radioisotope dating could now hone down when the Deccan eruptions occurred to within 30,000 to 65,000 years. "That could help put to bed some of the disputes regarding the issue," he said. Keller and her collaborator Thierry Adatte at the University of Neuchatel in Switzerland detailed their findings Oct. 31 at the annual meeting of the Geological Society of America in Denver.

- Image Gallery: Dinosaur Fossils

- Greatest Mysteries: What Causes Mass Extinctions?

- All About Dinosaurs

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.