Life Endures 120,000 Years Under Ice

Being tiny has its advantages, and a newly discovered microbe in Greenland has exploited this fully. The bacterium survived more than 120,000 years beneath the ice where inhospitable conditions reach new lows.

Most organisms constantly deal with trade-offs, such as some hot-desert residents that take advantage of sunshine yet must endure dehydration.

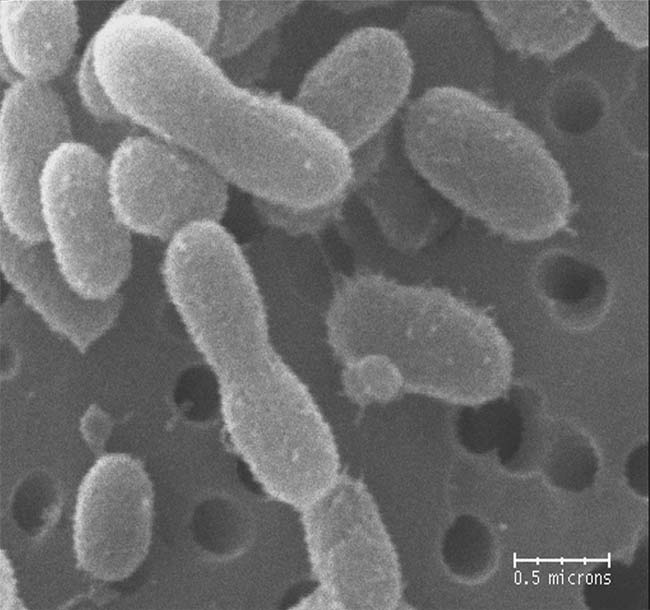

The new microbe makes dehydration seem like a walk in the park. Called Chryseobacterium greenlandensis, the tiny bacterium was found 2 miles (3.2 km) beneath a Greenland glacier. There, conditions are extreme, with temperatures below 16 degrees F (-9 degrees C), high pressure, very little oxygen and meager food.

The ultra-small size of the new species — about 10 to 100 times smaller than E. coli bacteria — could explain why it was able to gain a foothold in such harsh conditions and survive for so long, scientists say. Tiny microbes like this one likely can more efficiently absorb nutrients due to a larger surface-to-volume ratio. They also may be able to hide more easily from predators and take up residence in microenvironments, such as microscopic veins or cracks in the ice.

"These organisms end up in the ice, because they were deposited there when the glacier was being formed," said Penn State researcher Jennifer Loveland-Curtze. "If they were extruded into the veins, then that would be a place they might have been able to survive." Liquids in these veins often contain nutrients.

Loveland-Curtze, Penn State researcher Jean Brenchley and colleagues analyzed the genetic, physiological, biochemical and structural features of the new species. They hope to learn more about how cells survive extreme life, and ultimately, how life, in general, could survive in extreme environments on Earth and beyond.

"These very icy environments, the glaciers and permafrost, are great analogs for say Mars or Europa and even planets in solar systems we don't even know about yet," Loveland-Curtze told LiveScience.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Fewer than 8,000 species of microbes, out of the estimated 3 million presumed to exist on Earth, have been identified to date. And only 10 or so microbe species originating in polar ice and glaciers have been described.

Loveland-Curtze will present the research this week at a meeting of the American Society for Microbiology in Boston. The study was supported by the National Science Foundation, U.S. Department of Energy and NASA.

Last week, a different group announced that microbes are far more abundant on the seafloor than was expected.

- Video: Crustacean Mystery

- The Invisible World: All About Microbes

- Top 10 Amazing Animal Abilities

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.