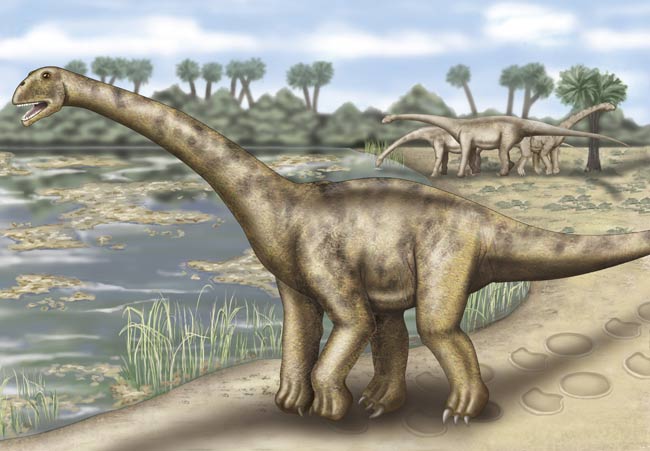

How Brachiosaurs Got So Huge

Brachiosaurs and other long-necked giants of the dinosaur world weighed as much as 10 African elephants. Researchers now think they know why the tubby vegetarian beasts got so big: They swallowed high-energy foods whole.

Their small heads helped, too, by allowing those long necks to reach nutritious leaves high up in the trees.

With body lengths of more than 131 feet (40 m) and heights of 56 feet (17 m), sauropods dwarfed meat-eating dinosaurs and even the largest land mammals ever. Sauropods appeared on the scene about 210 million years ago in the Late Triassic and dominated Earth's ecosystems for more than 100 million years from the Middle Jurassic to the end of the Cretaceous.

P. Martin Sander, a paleontologist at the University of Bonn in Germany, and Marcus Clauss of the University of Zurich propose how the plant-eaters could have reached such super sizes and thrive for so long.

For one, unlike duck-billed and horned dinosaurs, sauropods must not have listened to mom, as they didn't chew their food. In general, food chewing and the associated saliva that gets mixed in help to digest food.

Sauropods instead relied on giant bellies for storing lots of food, which could take a long time to digest. Past research has shown that the ferns and other plant material eaten by sauropods packed high amounts of energy needed for growth.

Smaller jaws

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

While a complex gut region was necessary, sauropods didn't need big jaws since they didn't chew their food. The smaller jaws meant sauropods could have small heads, which was a prerequisite for having a lengthy neck (their necks couldn't support too much weight). The neck meant the beasts could snag food that was out of reach for their stumpy-necked neighbors.

But life's tough for big guys. For instance, getting rid of excess body heat could have posed a problem for such a big body. And with such a long neck, a large volume of air had to trek through the also-lengthy windpipe before that fresh air reached the lungs.

These dinosaurs solved both problems with a bird-like breathing system. Instead of flexible lungs that expand and contract, sauropods (and modern birds) had a system of air sacs that pumped air through rigid lungs. Other air sacs and hollow spaces lined the spinal column and helped to shuttle unwanted heat away from the body core.

Sauropod eggs

Sauropods also had staying power. One way their giant genes survived involved sauropod reproductive biology. While mammalian plant-eaters give birth to one offspring at a time, sauropods laid several small eggs at once. This would help to increase the dinosaurs' population size and therefore lower the chances of extinction.

Once hatched, the tiny dinosaurs would grow from about 22 pounds (10 kg) to a fully-grown weight at rates similar to those of land mammals. The fast growth would mean a sauropod would quickly reap the benefits of being so large, such as protection from predators.

The researchers suggest sauropod gigantism may have led to the oversized meat-eating dinosaurs, which also were much larger than carnivorous land mammals. One idea is that sauropod eggs would have provided an easy feast for a growing meat-eater. Since mammals have few young that are well-protected, such a food source would be unavailable to meat-eating mammals.

The research, which will be detailed in the Oct. 10 issue of the journal Science, was funded by the German Research Foundation.

- Dino Quiz: Test Your Smarts

- Avian Ancestors: Dinosaurs That Learned to Fly

- Image Gallery: Dinosaur Fossils

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.