Ancient Fossil Suggests Origin of Cheetahs

A nearly complete skull of a primitive cheetah that sprinted about in China more than 2 million years ago suggests the agile cats originated in the Old World rather than in the Americas.

The skull was discovered in Gansu Province, China, and represents a new cheetah species, now dubbed Acinonyx kurteni, said Per Christiansen of the Zoological Museum in Denmark, who studied the fossil. The animal probably lived some time between 2.2 million and 2.5 million years ago, making the specimen one of the oldest cheetah fossils identified to date, he said.

Luke Hunter, executive director of Panthera, an organization that aims to conserve the world's wild cats, called the new find "extremely exciting stuff." [Photos: These Animals Used to Be Giants]

"We know amazingly little about the evolutionary history of most of the large cats, with the cheetah being a prime example: The existing fossils we have are largely similar to the modern cheetah," said Hunter, who was not involved in the current discovery.

Tom Rothwell of the Paris Hill Cat Hospital in New York, a specialist on ancient cats and dogs, agrees that the new skull is a "major find," though he cautions that it's difficult to declare it a new species. "There just is not enough data available from other specimens to be declaring this wonderful specimen a new and unique species," said Rothwell, who is a paleontologist and veterinarian.

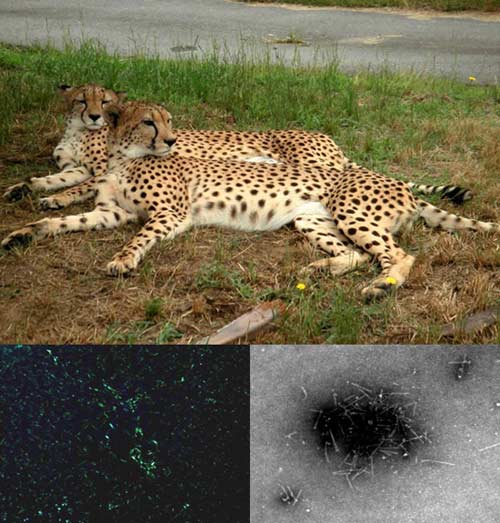

Cheetahs are the fastest land animals, capable of reaching speeds of 75 mph (120 kph), but they are not good climbers, unlike others in the cat family — Felidae. Still they are carnivores, like the other big cats. Today, cheetahs live primarily in Africa in the wild. Their status is threatened worldwide.

Cheetah features

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Scientists have long debated the origin of these super-fast felines, with clues coming from relatively few fossils. These include the European Acinonyx pardinensis with an estimated age of 2.2 million years, and the North African A. aicha, which dates to about 2.5 million years ago.

Making things more confusing, fossils of cheetah-like cats in the Miracinonyx genus (also called American cheetahs) have been discovered in North America.

"This new fossil is around as old as the oldest cheetah fossils we already have," Hunter told LiveScience, "but unlike all those, it has a unique set of 'primitive' characteristics that strongly suggest it is an earlier ancestor to all cheetahs, allowing us to go back deeper in the evolutionary sequence of the cheetah."

For instance, the cat had enlarged sinuses for air intake during sprinting, as do modern cheetahs. But its teeth showed primitive features.

"The enlarged sinuses cause the forehead of the skull to bulge. If you look at a cheetah's skull, it is remarkably tall and domed compared to similar sized cats such as pumas, ocelots or leopards, in particular around the upper nose region," Christiansen said.

"Our specimen also has a bulging nose, and, presumably large air sinuses for fast running," he said. "So running fast and becoming really good at it was one of the first steps in cheetah evolution. Later, the teeth changed as well."

Christiansen and Ji Mazák of the Shanghai Science and Technology Museum detailed the finding this week in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. The research was supported by a grant from the Carlsberg Foundation.

Cat home

The scientists say the newly analyzed cheetah is the most primitive known to date, which sheds light on cheetahs' original home.

"Because this new skull is more primitive than both cheetahs and Miracinonyx cats, and was found in China, it argues for a Eurasian/African ancestry of the entire group, with the Miracinonyx cats (or their ancestors) dispersing into the Americas later," Hunter said.

The new species brings the tally to five or six (scientists are not sure whether one of the previously found specimens is from a cheetah) cheetah and cheetah-like species known, with only one still alive today. (The living cheetah, Acinonyx jubatus, is found almost exclusively along African grasslands and semi-deserts.)

The findings also have implications for the conservation of today's big cats.

"It suggests that the 'sprinting cat' specialization is a fragile one, prone to extinction even under natural circumstances," Hunter said. "In light of this, we need to remind ourselves how imperiled the cheetah of today finds itself, where the threats are primarily human ones. If we lose this cheetah, it would be the end of this wonderful, unique lineage of sprinting cats."

In fact, cheetahs are currently in danger of extinction. "Fossil felids have clearly been hypercarnivores for a long time," Rothwell said, referring to cheetahs and other cats that exclusively eat meat. "They have never been diverse and, due to Homo sapiens proliferation, are now in extreme danger of extinction."

He added, "Tigers will soon be more plentiful in zoos than in the wild. How many more human generations before wild cheetahs are extinct?"

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.