Monkeys Ponder What Could Have Been

It's a good thing monkeys can't gamble. New research shows these primates are capable of "woulda-coulda-shoulda" thoughts, like those that keep gamblers at the tables.

Monkeys' brains respond to rewards that they observe but do not experience — so-called fictive outcomes — and monkeys change their behavior when they are shown the prizes that they could have had, researchers from Duke University Medical Center say.

"Monkeys appear to be able to use fictive information to guide their behavior, so they’re not purely guided by their direct experience of reward and punishment," said Michael Platt, the study's senior author.

This is one of the first studies to look at fictive thinking in animals, he said. The results are detailed in the May 15 issue of the journal Science.

Monkey thoughts

To study the monkey thought process, the scientists focused on the anterior cingulated cortex (ACC), a region of the brain thought to be involved in learning from experiences and adapting behavior. They monitored the monkeys' brain neurons while the animals played a game designed to study fictive thinking.

The monkeys were shown eight white cards arranged in a circle. Each card had a color underneath that corresponded to a specific reward, in this case, a certain amount of juice. One prize was larger than the others — a high value reward. Over many trials, the monkey learned to associate the color green with the biggest reward. After the monkey picked a card, all the cards were turned over, and the monkey was shown the prizes that it missed, and then given the reward.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The researchers found that the neural response was proportional to the reward given — the bigger the reward, the more the neurons fired. And the neurons responded the same way to fictive rewards. This result shows that "nerve cells in the ACC, which we already knew carry information about experienced rewards, also carry information about fictive rewards, information about the rewards that got away," said Platt.

Learning from mistakes

The monkeys also altered their behavior depending on the size of the fictive reward.

If the monkey missed out on a big reward in one trial, it was more likely to choose the card that had offered that large reward in the next trial. This is similar to what people do when they gamble. For example, if someone is playing roulette and bets on black, but red wins and pays off big, the person is more likely to bet on red the next time.

Fictive thinking may have helped the monkeys learn as well. During the trials, the large reward was kept in the same spot 60 percent of the time or moved clockwise by one position in order to see if the monkey would pick up on the pattern. Indeed, they did. The monkeys chose cards next to possible high value rewards in 38 percent of the trials, while they chose cards adjacent to low value rewards in only 17 percent of trials.

The research was funded by a fellowship from the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

- Video: Expanding Chimps Minds

- Monkeys Like to Gamble

- Video: Clever Primates

Rachael is a Live Science contributor, and was a former channel editor and senior writer for Live Science between 2010 and 2022. She has a master's degree in journalism from New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. She also holds a B.S. in molecular biology and an M.S. in biology from the University of California, San Diego. Her work has appeared in Scienceline, The Washington Post and Scientific American.

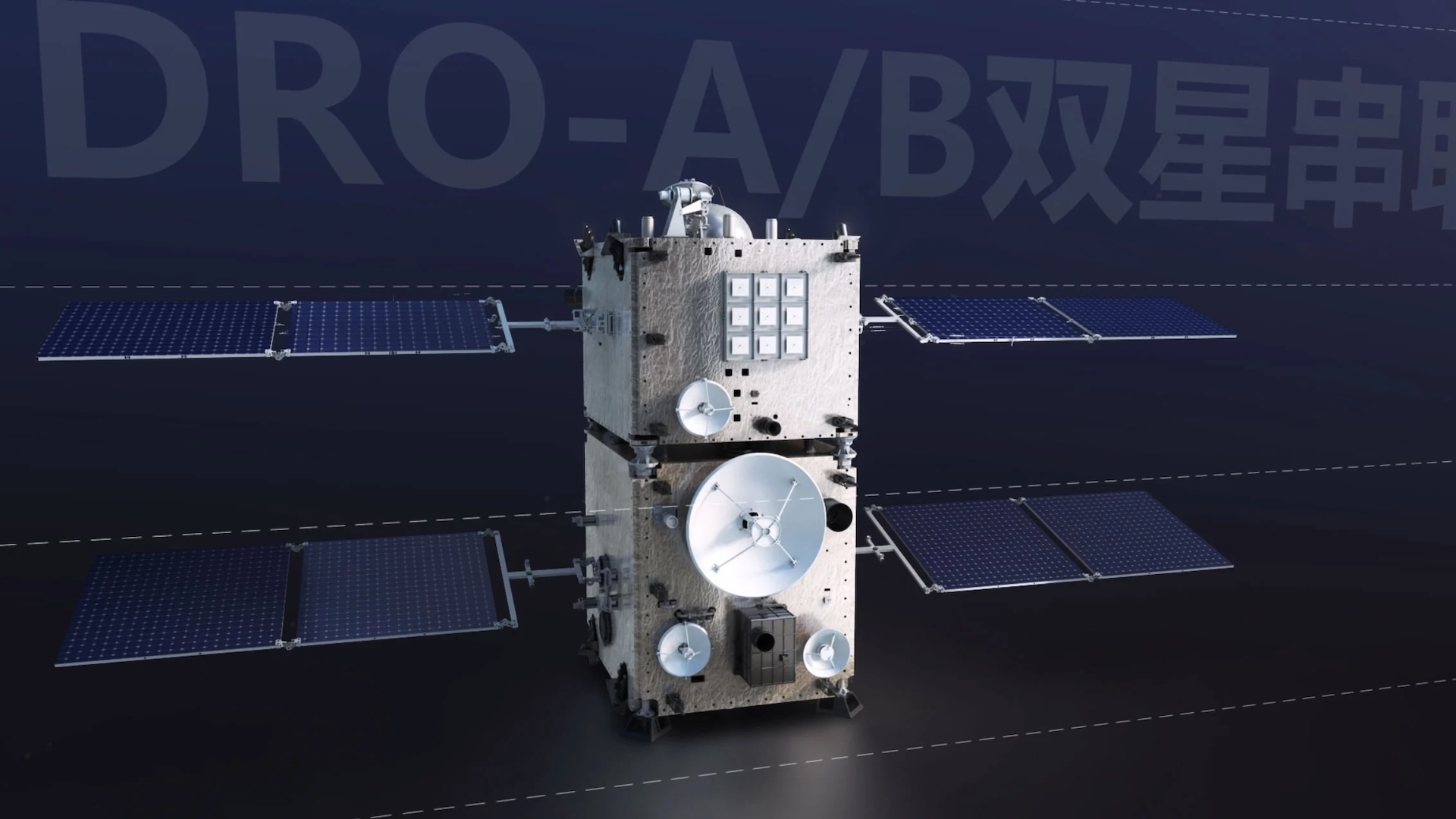

China uses 'gravitational slingshots' to save 2 satellites that were stuck in the wrong orbit for 123 days

Scientists spot a 'dark nebula' being torn apart by rowdy infant stars — offering clues about our own solar system's past

Mass graves of Black Union soldiers slaughtered by Confederate guerrillas possibly identified in Kentucky