Life Could Have Survived Earth's Early Bombardment

An asteroid bombardment of Earth nearly 4 billion years ago may have actually been a boon to early life on the planet, instead of wiping it out or preventing it from originating, a new study suggests.

Asteroids, comets and other impactors from space have been suggested as the causes behind some of the world's great mass extinctions, including the disappearance of the dinosaurs.

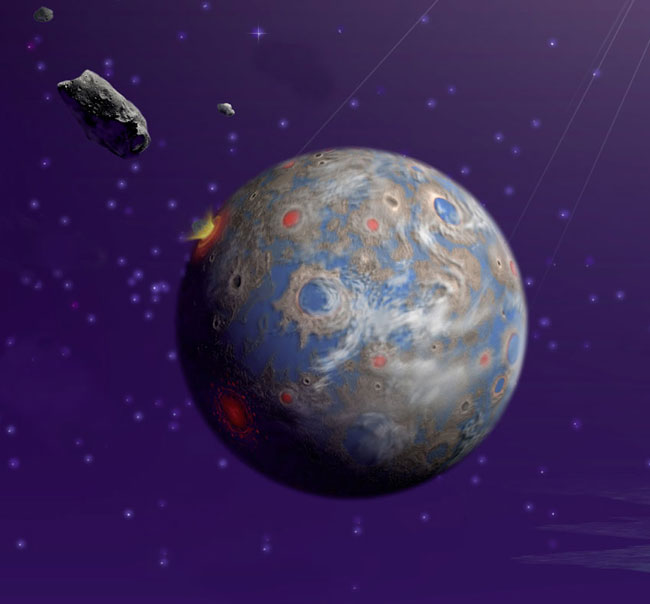

Impact evidence from lunar samples, meteorites and the pockmarked surfaces of the inner planets paints a picture of a violent environment in the solar system during the Hadean Eon 4.5 to 3.8 billion years ago, particularly through a cataclysmic event known as the Late Heavy Bombardment about 3.9 million years ago.

No such record exists for Earth because tectonic processes have folded ancient craters back into the interior, but scientists assume our planet took the same pummeling.

Although many believe the bombardment would have sterilized Earth, the new study uses a computer model to show it would have melted only a fraction of Earth's crust, and that microbes — if any existed in the first 500 million years or so of Earth's existence — could well have survived in subsurface habitats, insulated from the destruction.

"These new results push back the possible beginnings of life on Earth to well before the bombardment period 3.9 billion years ago," said CU-Boulder Research Associate Oleg Abramov. "It opens up the possibility that life emerged as far back as 4.4 billion years ago, about the time the first oceans are thought to have formed."

Modeling the bombardment

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Because physical evidence of Earth's early bombardment has been erased by weathering and plate tectonics over the eons, Abramov and his colleagues used data from Apollo moon rocks, impact records from the moon, Mars and Mercury, and previous theoretical studies to build three-dimensional computer models that replicate the bombardment.

The researchers plugged in asteroid size, frequency and distribution estimates into their simulations to chart the damage to the Earth during the Late Heavy Bombardment, which is thought to have lasted for 20 million to 200 million years.

The 3-D models allowed the researchers to monitor temperatures beneath individual craters to assess heating and cooling of the crust following large impacts in order to evaluate habitability, said Abramov. The study, detailed in the May 21 issue of the journal Nature, indicated that less than 25 percent of Earth's crust would have melted during such a bombardment.

The team even cranked up the intensity of the asteroid barrage in their simulations by 10-fold — an event that could have vaporized Earth's oceans.

"Even under the most extreme conditions we imposed, Earth would not have been completely sterilized by the bombardment," Abramov said.

Instead, hydrothermal vents may have provided sanctuaries for extreme, heat-loving microbes known as "hyperthermophilic bacteria" following bombardments, said study team member Stephen Mojzsis. Even if life had not emerged by 3.9 billion years ago, such underground havens could still have provided a "crucible" for life's origin on Earth, he added.

The modeling work was supported by the NASA Astrobiology Program's Exobiology and Evolutionary Biology Department and the NASA Postdoctoral Program.

Dawn of life

The researchers concluded subterranean microbes living at temperatures ranging from 175 degrees to 230 degrees Fahrenheit (79 degrees to 110 degrees Celsius) would have flourished during the Late Heavy Bombardment. The models indicate that underground habitats for such microbes increased in volume and duration as a result of the massive impacts.

Some extreme microbial species on Earth today — including so-called "unboilable bugs" discovered in hydrothermal vents in Yellowstone National Park — thrive at 250 F (120 C).

Geologic evidence suggests that life on Earth was present at least 3.83 billion years ago, Mojzsis said.

"So it is not unreasonable to suggest there was life on Earth before 3.9 billion years ago," he added. "We know from the geochemical record that our planet was eminently habitable by that time, and this new study sews up a major problem in origins of life studies by sweeping away the necessity for multiple origins of life on Earth."

The results also support the potential for microbial life on other planets like Mars and perhaps even rocky, Earth-like planets in other solar systems that may have been resurfaced by impacts, Abramov said.

"Exactly when life originated on Earth is a hotly debated topic," says NASA's Astrobiology Discipline Scientist Michael H. New. "These findings are significant because they indicate life could have begun well before the [Late Heavy Bombardment], during the so-called Hadean Eon of Earth's history 3.8 billion to 4.5 billion years ago."