Humpback Dinosaur Surprises and Puzzles Experts

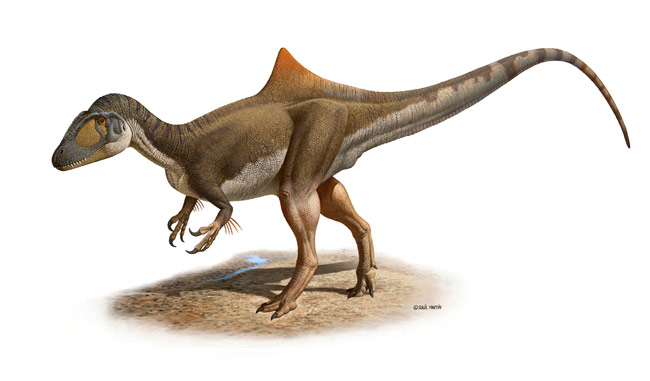

A hunchback dinosaur of sorts once roamed what is now central Spain. The meat-eating beast sported a humplike structure low on its back, a feature never previously described in dinosaurs, and one that has scientists scratching their heads.

The dinosaur, which is being called Concavenator corcovatus, measured nearly 20 feet (6 meters) in length and belonged to a group of some of the largest predatory dinosaurs known to walk the earth — carcharodontosaurs. It lived some 125 million years ago.

A nearly complete skeleton of the dinosaur revealed a few unique features. For instance, the last two vertebrae in front of the pelvis, in the hip area, were elongated, with spines projecting onto the back to form a hump.

"Wow," Jack L. Conrad, a vertebrate paleontologist at the American Museum of Natural History in New York, said of the Spanish discovery. "Overall it's such a bizarre animal." [Reconstruction of humpback dinosaur]

The researchers examining the bones from an archaeological dig in Cuenca, east of Madrid, so far can only speculate about the hump's function. "Probably the most plausible role for this structure is that of a deposit of fat, as occurs in some modern mammal such as in the zebu," said Francisco Ortega of the Universidad Nacional de Educacíon a Distancia, in Madrid. The zebu is an ox with a large hump over its shoulders.

However, unlike the humps on mammals, Concavenator's had an internal bony structure.

"A structure as striking as that presented by Concavenator could play a role also in communication between individuals of the same species," Ortega told LiveScience. He added that the hump also may have supported a fold of skin that helped in regulating the creature's body heat.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Ortega and two colleagues report their findings in the Sept. 9 edition of the journal Nature

Conrad, who was not involved in the findings, thinks the hump was ornamental, possibly serving to woo mates.

Little scars on the forearm bones suggest the presence of spiky, rigid structures, which may have been wing feathers.

"The scars on the bone look, from what I can tell, exactly like the scars left on an arm bone of a chicken or some other modern bird, and in general those are for large wing feathers," Conrad said during a telephone interview.

If they were indeed feathers — an idea that's only speculation at this point, but something that Conrad said wouldn't surprise him — they would be meaningful for the field.

"If this animal had wings, that would really push back the origin of wings, and it would basically really lock in that wings didn't appear for flight first; more likely they appeared for display," Conrad said.

- 25 Amazing Ancient Beasts

- Avian Ancestors: Dinosaurs That Learned to Fly

- Images: Dinosaur Drawings

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.