Ancient Carnivorous Insect Sported Snowshoes

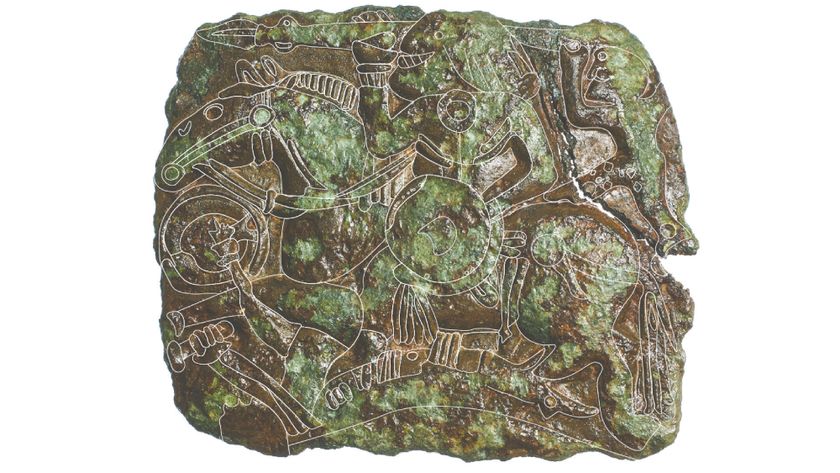

The fossilized remains of a predatory insect suggest its descendants — large, meat-eating crickets — have been stuck in time for the past 100 million years or so.

The insect, whose remains were found in a limestone fossil bed in northeastern Brazil, lived during the Early Cretaceous Period, when dinosaurs ruled the planet just before the breakup of the supercontinent Gondwana.

When alive, the beefy insect, stretching 2 inches (6 centimeters) from head to bum, would've been quite an oddball — sporting antennae longer than its body, tightly coiled wings on its back and snowshoes of sorts on its feet for traversing its sandy environment.

The only other specimen of this species was described in 2007 and placed in its own genus Brauckmannia groeningae, as the scientist didn't know where the organism belonged.

With a new and nearly complete specimen of that species, the researchers provide a more detailed and accurate description of the ancient insect, revealing its true identity as a species of the living genus Schizodactylus, or splay-footed crickets, which also includes true crickets, katydids and grasshoppers.

"They get their common name from the large, paddle-like projections on their feet, which help support their large bodies as they move around their sandy habitats, hunting down prey," said University of Illinois entomologist Sam Heads, of the Illinois Natural History Survey, and lead author of the paper describing the new species in the journal ZooKeys.

When snagging prey, these species have no particular strategy. "They come out mostly at night and they'll crawl around their dune-like habitats and occasionally run down a prey item," Heads said. "They can be quite quick when they need to. … They're quite voracious."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

During a phone conversation, he recalled, "Having seen these myself in the wild, when you try to pick the things up they give a pretty good fight."

Being so fast and aggressive, the meaty insects likely had no reason to fly, Heads said, though they probably would've been able to uncoil their wings if the need arose.

The Schizodactylus specimen had features that were different enough from other members of the genus to warrant its own species (Schizodactylus groeningae). For instance, its legs and the lobe-shaped structures on its feet had slightly different shapes than species living today.

Even so, its general features differ very little, Heads said, revealing that the genus has been in a period of "evolutionary stasis" for at least the last 100 million years. "It's obviously doing something right," Heads said of the new species and its body plan.

In addition, other studies have shown that where the fossil was found was most likely an arid or semi-arid monsoonal environment during the Early Cretaceous Period, suggesting that even the habitat preferences of Schizodactylus have changed little since then, he said.

You can follow LiveScience managing editor Jeanna Bryner on Twitter @jeannabryner.

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.