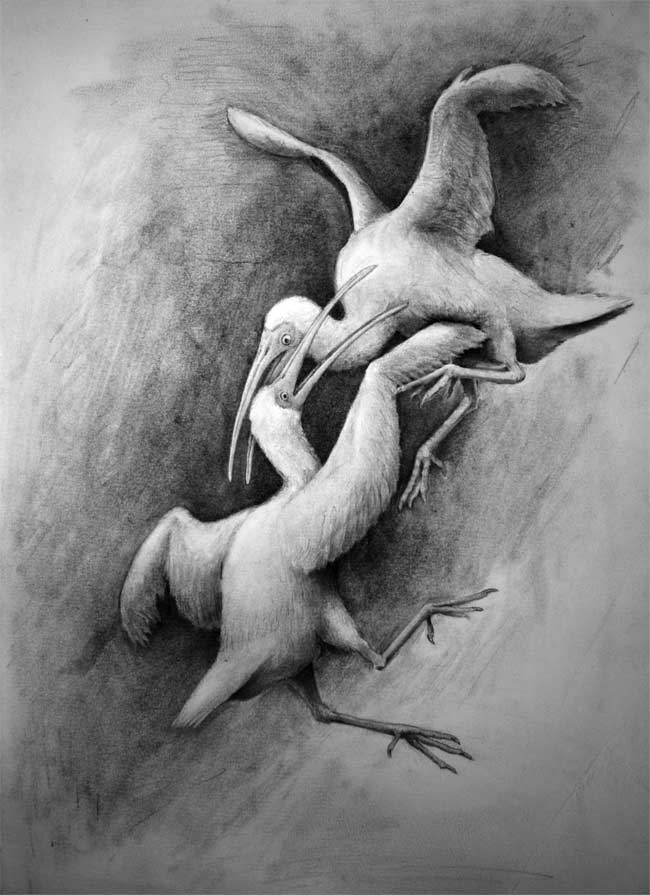

Ancient 'Ninja' Birds Swung Wings Like Nunchucks

An extinct bird from Jamaica apparently transformed its wings into banana-shaped clubs to beat its enemies with, scientists find.

The peculiar, roughly chicken-size ibis Xenicibis xympithecus probably went extinct less than 10,000 years ago, and may have been another casualty of humanity. It was flightless, just as many island birds are, but the 5-pound (2 kilogram) ibis nevertheless retained long wing bones.

Surprisingly, the "hands" of this bird apparently became massive curved weapons.

"There's just nothing else out there like this in any other vertebrate," researcher Nicholas Longrich, a vertebrate paleontologist at Yale University, told LiveScience. "Usually evolution tends to hit on the same designs over and over, and this is just something completely different, so as a biologist it's sort of cool to find something and be able to say, 'Wow, I haven't seen that one before.'"

Their bizarrely distorted hands had short, block-like fingers, long palm bones thicker than their thighbones, and wrist joints that allowed the wings to swing rapidly like clubs.

"I sometimes compare these things to nunchucks, which I guess would make this a ninja bird, although perhaps a better analogy would be a pair of baseball bats — they were actively swung rather than moving passively like a flail or nunchaku," Longrich said.

Broken wing bones the researchers discovered suggest these clubs were used and abused in combat.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"These are pretty effective weapons, swung with enough force to break bones," Longrich said. "They weren't screwing around — these birds are taking and receiving some serious blows. They're angry birds."

When Longrich first saw the wings, "I thought they had to be a deformity," he said. "I couldn't believe that these were the natural shape of the bones — they were just too strange and bizarre."

He recalled that ornithologist Storrs Olson at the Smithsonian Institution "had told me, 'the hand is shaped like a banana,' and I assumed he was exaggerating, and then I saw them and I thought, 'Wow. The hand is shaped like a banana.'"

"It was really a challenge figuring out what these wings might be for," Longrich added. "We threw around all kinds of ideas — that the bird used the wings for climbing, or for digging, or even that the bird moved on all fours and it used the wings to help it walk. They were just so bizarre, we had no comparison, so no idea was too weird to rule out. I hit on the idea that they were weapons because it was the least strange idea. Although no other bird has wings like this, a lot of birds do use the wings as weapons — swans, geese, plovers, jacanas, screamers and so forth."

Modern ibises are highly territorial during nesting and feeding and often fight, suggesting the clubs of these extinct birds were probably used against other members of their species. Indeed, some living ibises are known to grasp their opponents with their beaks and then strike with their wings. On the other hand, they might have been used to defend their nests and young from the many predators on the tropical Caribbean island, such as snakes, monkeys and hawks.

Although these ibises are the first creatures with a backbone known to have modified their limbs into clubs, they are not the first animals known to have done so. For instance, some mantis shrimps have club-like appendages they use to strike prey and members of their own species.

One interesting detail about these ibis wings is that there appears to be no variation in them between the sexes. "Males and females alike would have had them," Longrich said. "So, if they were using them in territorial battles, males and females might be working together to defend a territory, instead of just the male fighting."

Longrich and Olson detailed their findings online Jan. 4 in the Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

- 25 Amazing Ancient Beasts

- Rumor or Reality: The Creatures of Cryptozoology

- Image Gallery: Rare and Exotic Birds

You can follow LiveScience on Twitter @livescience.