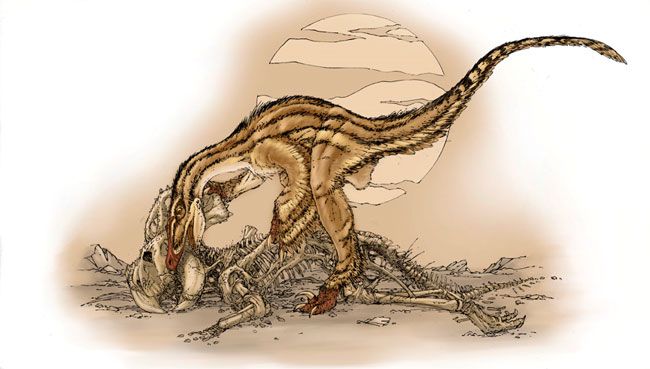

Velociraptor Frozen in Time Scavenging a Larger Dinosaur

The swift predator Velociraptor has been caught frozen in time apparently scavenging on the corpse of another, larger dinosaur, scientists now reveal.

Not only did grooves from the raptor's teeth mar bones belonging to the sheep-sized horned herbivore Protoceratops, but paleontologists also discovered fossil remnants of the hunter's teeth alongside the plant-eater that match the marks.

The fossils, unearthed from a red sandstone mound in Inner Mongolia, China, in 2008, consist of a collection of heavily eroded Protoceratops bones with two small, curved, serrated teeth that belonged either to Velociraptor or a close relative. Back when they lived roughly 65 million to 70 million years ago, the area was probably a scrubby desert with lots of sand and rocks and not too much vegetation, though there were bodies of water, with life quite lush closer to the rivers.

The size of the Velociraptor and Protoceratops teeth suggest they came from adults. The raptor was roughly 5 feet long (1.5 meters), while the herbivore might have been anywhere from 4.6 to 6.5 feet long (1.4 to 2 m).

Bite marks on and around the herbivore's jaws suggest the raptor did not kill the plant-eater, but was instead scavenging on its carcass.

"This is a big animal, packing lots of muscle and lots to eat. Why then, would the killer be biting away on the cheeks and jaws so heavily that it lost a couple of teeth and left marks on the bones? The obvious answer is this didn't happen," explained researcher David Hone, a paleontologist at the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology of China in Beijing.

Instead, when the raptor got there, "this was a carcass with little left on, and it was scraping off the last accessible fragments of meat on the bones," Hone said. "This pattern is also seen in living carnivores — when faced with a large body, they start on the belly and hindlegs and the head is nearly always the last to go. Here the skull and jaws are the bones with the marks on and thus most likely to be the bits left over, not those first taken on."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

These new findings support a famous discovery made more than 30 years ago in Mongolia seemingly of a Velociraptor and Protoceratops locked in mortal combat. Although these fossils, dubbed the "fighting dinosaurs," certainly suggested the raptor hunted the herbivores, one could readily argue such an instance was a chance encounter, with Velociraptor only rarely eating Protoceratops.

The "fighting dinosaurs" suggest Velociraptor could act as a predator, while this new find suggests it could act as a scavenger. This is true of many living carnivores as well, Hone said, such as lions and jackals.

It remains unknown as to what might have killed the Protoceratops, as its bones were simply not well preserved enough. "They probably were once in magnificent condition, but they had eroded," Hone said. "If we'd got there a few months earlier it might have been a perfect specimen — a month or two later and we might have found nothing but dust."

Hone and his colleagues will detail their findings in an upcoming issue of the journal Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology.