Bees Wiped Out by Cascade of Deadly Events

Bees across the United States have succumbed in recent years to a treacherous alien mite that invaded the country two decades ago. But scientists haven't been able to figure out why the parasite is so destructive.

Up to 60 percent of hives in some regions have been wiped out. Entire colonies can collapse within two weeks of being infested. North Carolina fears it is on the verge of an agricultural crisis. No state is immune.

A new study suggests the killing mechanism is complex.

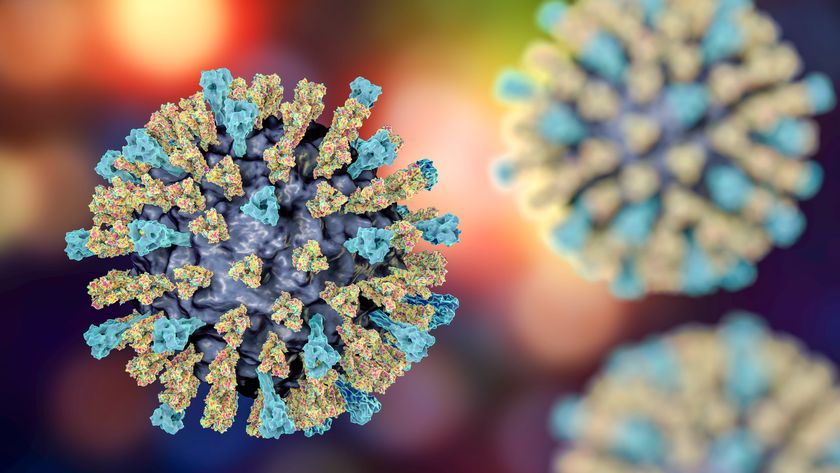

The mites feed on bees, and they suppress the bee's immune systems. That opens the door for a virus that deforms bee wings to take over. The entire hive, even its food source, gets infected.

Agricultural headache

Agriculture in the United States depends on the European honeybee. As much as a third of the American diet is tied to their ability to pollinate crops that total in the billions of dollars every year.

The bees' nemesis, the eight-legged Varroa destructor mite, is the size of a pin head. It feeds on the blood of adult bees and also eats bee larvae.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The mites are resistant to pesticides. Breeding programs designed to develop bees that can resist the mite have so far been unsuccessful.

Researchers suspect the mite arrived on Chinese honeybees around 1987. The Chinese bees know how to deal with the parasite.

"The native Chinese bees do not have the same problems," said Xiaolong Yang, a post-doctoral researcher in entomology and plant pathology at Penn State who raised bees in China. "I do not recall seeing deformed wing bees in the Chinese bee. Chinese honeybees have grooming behavior which can remove the mites from the bees. They get rid of the mites."

While researchers know that the Varroa mite is behind the death of bee colonies, the mechanism causing the deaths is still unknown. Yang and Dr. Diana L. Cox-Foster, Penn State professor of entomology, now believe that a combination of bee mites, deformed wing virus and bacteria is causing the problems occurring in hives across the country.

"Once one mite begins to feed on a developing bee, all the subsequent mites will use the same feeding location," Cox-Foster said today. "Yang has seen as many as 11 adult mites feeding off of one bee. Other researchers have shown that both harmful and harmless bacteria may infect the feeding location."

Downward spiral

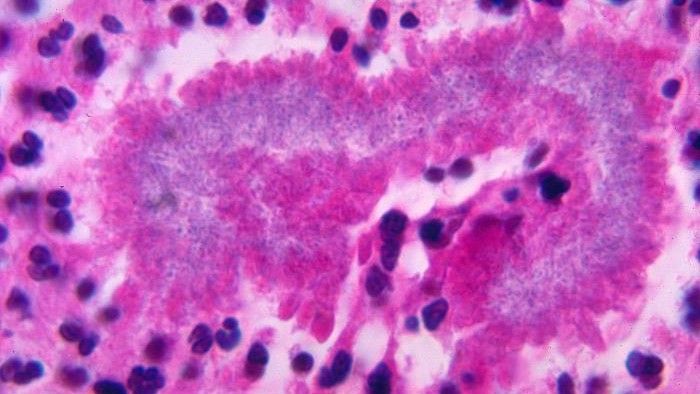

European honeybees in the United States have long dealt with a virus that deforms their wings. Alone, the virus does not threaten colonies, however. The bee mite infestation seems to raise the number of deformed wing virus cases to about 25 percent of a population.

Yang and Cox-Foster injected bacteria into bees. In mite-infested bees, the deformed wing virus blossomed rapidly. In mite-free bees, it didn't change.

A final, fatal step is involved. Worker bees put a sterilizing agent into honey and the colony's food. Mite-infested bees can't produce as much of the agent. Cox-Foster suspects the honey then carries more bacteria.

"It is likely that the combination of increased mite infestation, virus infection and bacteria is the cause of the two-week death collapse of hives," she said.

The results are detailed today in the online version of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Science.

Meanwhile, some researchers have advocated fostering dwindling populations of wild honeybees. Some 4,000 species are native to North America. While most seem to resist the mite, their numbers have shrunk due to pesticide use and changes to the land. Wild bees often nest in the ground and can't survive in an agricultural setting.

Related Stories

- Tiny Pest Decimating Honeybee Colonies

- N.C. Bee Shortage Could Lead to 'Agriculture Crisis'

- How Did Bees Survive Dino-Killing Asteroid?

Up Close

Photo: USDA/Scott Bauer

Image Gallery

Robert is an independent health and science journalist and writer based in Phoenix, Arizona. He is a former editor-in-chief of Live Science with over 20 years of experience as a reporter and editor. He has worked on websites such as Space.com and Tom's Guide, and is a contributor on Medium, covering how we age and how to optimize the mind and body through time. He has a journalism degree from Humboldt State University in California.