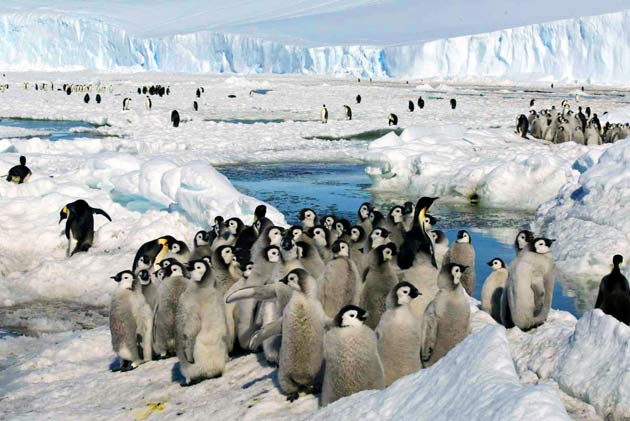

Mating March of the Penguin Slows Down

Penguins and other Antarctic seabirds are nesting and laying their eggs later than they did 50 years ago, a response, scientists say, to global climate change.

While the effects of climate change on animal behavior have been well documented in the Northern Hemisphere, the effects are less well known south of the equator. In North America and Europe, cold-weather animals are generally shifting northward as the Arctic warms and the ice cap shrinks.

A new study by two scientists at the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique in France compiled data for Antarctic seabird nesting from 1950 to 2004. It reveals that nine species of birds are, on average, arriving nine days later to nest. The birds are also laying their eggs two days later.

Upside down

This runs opposite to shifts in avian habits in the Northern Hemisphere, where earlier springs and increased food availability has led to birds migrating and laying eggs earlier in the season.

In Antarctica, the delay appears to be tied to sea ice.

Unlike western Antarctica, no major warming or cooling has occurred in eastern Antarctica since the 1950's. However, in eastern Antarctica, sea-ice range has reduced 12 to 20 percent since the 1950's, owing to global warming, scientists say. Yet localized cooling has caused the sea-ice season to increase by more than 40 days since the 1970's.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

These changes have been associated with a decline in abundances of krill and other marine organisms that are food resources for most Antarctic seabirds.

This may partly explain the delay in seabirds' arrival and laying dates, the researchers say, since seabirds need more time to build up the reserves necessary for breeding.

Get to it

The shift represents a seven-day compression of the prelaying period when birds set up territories, court, and females make their eggs, suggesting that the birds' reproductive processes have some plasticity.

However, the scientists caution, if the seabirds continue to become less synchronized with their food source, and the sea ice continues to block their nesting sites, these species could suffer if they fail to respond appropriately, either through microevolution or behavior changes, to climate change.

This study is detailed in the April 3 online edition of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. The species affected: emperor penguin, Adelie penguin, southern giant petrel, southern fulmar, Antarctic petrel, Cape petrel, snow petrel, Wilson's storm petrel and the south polar skua.

- Shifting Icebergs May Have Forced Penguin Evolution

- How Global Warming is Changing the Wild Kingdom

- Animals and Plants Adapting to Climate Change

- More Frogs Dying as Planet Warms

Hot Topic

The Controversy

- Conflicting Claims on Global Warming and Why It's All Moot

- Baffled Scientists Say Less Sunlight Reaching Earth

- Scientists Clueless over Sun's Effect on Earth

- Key Argument for Global Warming Critics Evaporates

The Effects

- Seas to Rise

- Ground Collapses

- Allergies Get Worse

- Rivers Melt Sooner in Spring

- Increased Plant Production

- Animals Change Behavior

- Hurricanes Get Stronger

- Lakes Disappear

The Possibilities

- More Rain but Less Water

- Ice-Free Arctic Summers

- Overwhelmed Storm Drains

- Worst Mass Extinction Ever

- A Chilled Planet

Strange Solutions